Why Every Protest in India turns into a Violent Protest 2022?

Why Every Protest in India turns into a Violent Protest?

A protest is a kind of demonstration intended to sway public opinion, express dissatisfaction, bring attention to injustice, or provide information about something in your community. You may well have a small demonstration with one individual opposing any kind of concept or action, such as criticizing your school’s lunch menu. There may be major public protests at the state and national levels.

The sit-ins and demonstrations organized by Black Lives Matter are well-known examples of worldwide mass protests. There are many famous protests that occurred during the Civil Rights Movement, for example. To comprehend a demonstration comprehend what a demonstration is, it’s necessary to examine the many forms of protest.

Protests of Various Types

There are usually two distinct groups when it depends on different forms of protests. Nonviolent protests are when an individual or a group of people band together to bring about change in a nonviolent way. Violent demonstrations, sometimes known as riots, promote change by the use of violence, destruction, or intimidation. Violent protests can begin as nonviolent protests or be spurred by dissatisfaction into a violent protest. Examine the various sorts of demonstrations and examples of each.

Protests through Sitting-In

A sit-in demonstration is exactly what it sounds like. It’s a kind of civil disobedience in which you sit publicly to protest a specific action. When African Americans were denied service and ordered to move, they sat in the white parts of a segregated lunch area in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960. Sit-ins not only generate media attention but also generate sympathy.

Rallies and Marches

A walk or rally is a nonviolent demonstration in which a group assembles with signs, banners, and other materials to spread information about a cause. Marches may also have speakers who will provide information about the reason. Marches throughout cities and capitals denouncing lockdowns amid the COVID outbreak were among the most well-known events in 2020. The March on Washington by African-Americans protesting Jim Crow restrictions is a famous historical march.

Strike Against Hunger

During a hunger strike, activists fast for a set period to pressure a government to change its position on a particular subject. Inhumane conditions, political purposes, or bringing attention to a problem are examples of these. Cesar Chavez, a Mexican-American, launched a notable historical hunger strike to promote farmworkers and labour.

The flag is on fire.

The destruction of a flag is another type of political demonstration that a person or a group might engage in. Burning the flag, which is usually a criminal crime, enters the domain of violent protests because it’s being destroyed. When Paul Hopkins was convicted for killing the New Zealand flag in 2003, it became a famous flag-burning protest.

Riots, looting, and vandalism are all examples of vandalism.

When it came to violent protests, riots, looting, and vandalism usually go hand in hand. A riot occurs when a group of individuals expresses their anger or disapproval of a community or government. During a riot, the property might be trashed, stores looted, and fires started. A riot erupted at the United States Capitol Building in 2021 when a mob invaded the building while Congress tallying the Electoral College votes.

Protests are being bombed.

The use of explosives is another violent strategy used by protestors to garner attention. This might be a large-scale bombing or the use of firebombs during a riot. Bombs almost always result in injuries and deaths. In 1970, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a bombing protest became well-known. Four anti-Vietnam War demonstrators carried out the bombing, which was targeted at the Army Mathematics Research Center.

Some critics in the United States have stated that the bloodshed on their streets derives from a deep feeling of despair and despair that things would never change. Psychological studies back up this analysis. Activists may be more likely to use violent tactics of protest if they do not believe their appeal to authorities will be heard.

People believe they have “nothing to lose” in these circumstances. Overbearing policing might result in violence. Nevertheless, there is another essential factor to consider.

Contempt and powerlessness do not originate in a vacuum; they are the result of real-life interactions between individuals and communities.

We know from centuries of studies on policing and gatherings that the police’s harsh and heavy-handed conduct is a primary motivator for protest violence. People’s perceptions of the aim of the demonstration group are reshaped as a result of such events.

Over the last week, people who came out to exercise their fundamental right to peaceful protest have discovered that they are suddenly official enemies – dissidents in their very own nation. The protest’s goal takes on a considerably greater significance in these conditions.

Protesters have the ability to adapt their tactics.

Disregarding people’s safety and purpose is an intelligent method to make them feel despised. Even though most people believe aggressive protests are ineffective, our research demonstrates that when a government is perceived to be morally corrupt, people’s opinions alter.

To put it another way, if the government responds in an unjustifiable and disproportionate manner, even the average citizen may begin to consider violence increasingly acceptable.

In the first place, why do people protest?

Who could have predicted, given current limits on public gatherings, that we would be seeing such a massive worldwide solidarity movement in the midst of a terrible pandemic?

It has long been recognized that certain events can act as catalysts for social movements. Consider the acts of US civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks, who infamously insisted on her seat on an Alabama bus to a white man in 1955, prompting widespread opposition to the time’s racial segregation rules.

When Tunisian fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in December 2010 in protest of police misconduct and harassment, his actions were televised around the world, laying the groundwork for the Arab Spring.

According to research, people who protest do so because they are furious about injustices perpetrated against groups they care about and believe they can make a significant difference by cooperating. Importantly, in the twenty-first century, historical cases — and our emotions toward these — can now be streamed online and distributed to thousands of people all over the world in minutes.

Outrage and a common goal are generated via online exchanges.

These internet exchanges are more than just chit-chat. According to research, people’s protest commitments are established and maintained through internet discussions regarding injustice. People communicate online, creating a culture of mutual outrage and a belief that things may be different if “we” act together.

People who converse online about police deaths of Black people are far more likely to attend protests, according to research, specifically if they live in an area where police killings of Black people have historically been high.

Civil instability in India, such as violent mobs, protests, and riots, has put pressure on the country’s secular foundation. Movements have affected the nation’s history, whether it was the Swadeshi Movement in 1905 or the Satyagrah in 1930. ET Magazine examines some of the most significant protests in contemporary India as Tamil Nadu witnessed rallies and shutdowns demanding the establishment of the Cauvery Management Committee.

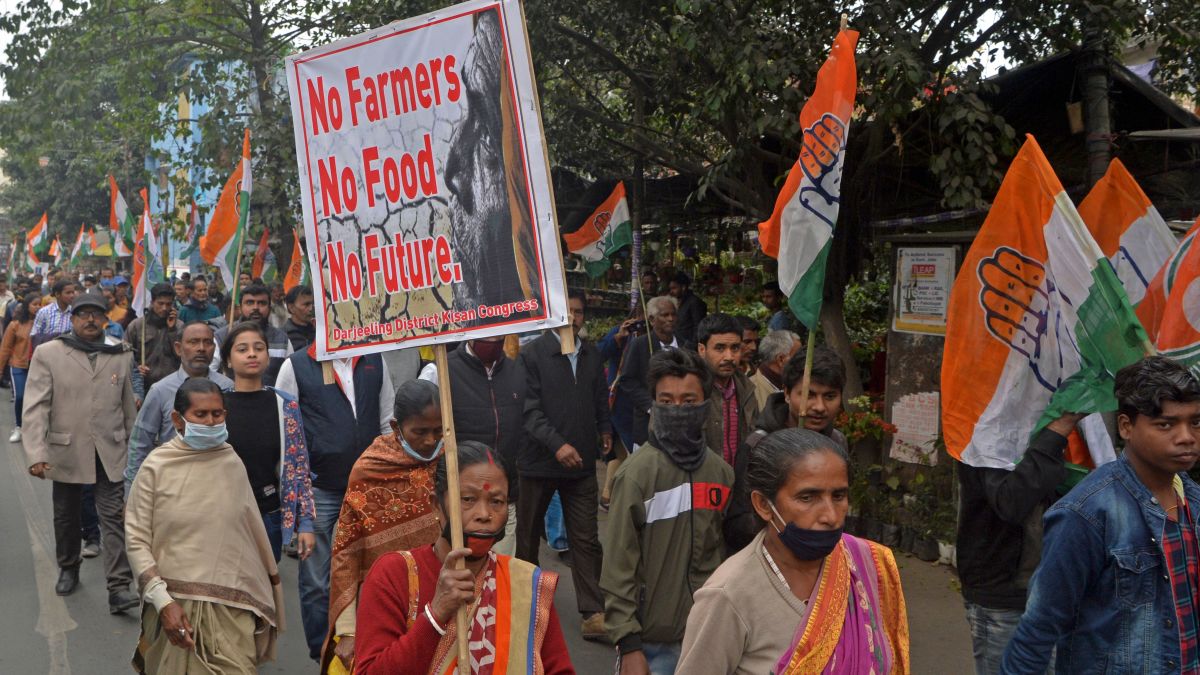

Thousands of farmers and activists, as well as foreign state and non-state players such as global warming activist Greta Thunberg and the United Nations, have joined farmers’ demonstrations in India. It is, without a doubt, the world’s largest protest. Farmers’ and workers’ unions planned a national strike on November 26, 2020, which drew 250 million people, or 75% of the total population of the United States. To say the least, these are historical figures. In India’s recent history, protests have played a significant role. Forcibly dispersing demonstrators can only be a negative for our country.

India’s democracy is inalienable.

India’s democratization processes are inextricably linked to mass movements, which have always played a key role in influencing national policy and law. The birth of India was a result of popular resistance to British rule, and many of our Prime Ministers and leadership were involved. Our founding fathers, particularly Gandhi, advocated for the average man trying to stand up for himself and voice his dissatisfaction with the regime’s policies. This history of protests is mirrored in India’s Constitution (Article-19), which gives it to our citizens as a right.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a forefather and design professional of our Constitution, predicted that protests would be rare in an independent India since other avenues of obtaining justice would be available. Since then, however, several popular movements have occurred in our country, bringing down administrations, initiating socio-economic and political transformations, and altering the structure of our institutions.

In 1977, Jayaprakash Narayan spearheaded nonviolent rallies that resulted in the fall of Indira Gandhi’s “invincible” autocratic government, a previously thought unachievable, and the election of the very first non-Congress government before our independence. Similarly, Anna Hazare’s anti-corruption campaign in 2011 played a crucial role in destabilizing India’s scandal-plagued central administration.

Protests have also been used to address social concerns such as rape, as seen by the large-scale movement following the Nirbhaya case in 2012-13, which compelled politicians to act quickly. Protests are so embedded in our culture that even Prime Minister Modi cannot ignore them. Modi has dubbed protesters Andolanjivi (protesters for the sake of protesting). In the 1970s and 1980s, he, too, was an Andolanjivi, criticizing the Congress administration.

It should also be highlighted that protest violence is inextricably linked to India’s mass movements and is not a new phenomenon following the accession of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) to power at the centre.

In fact, Hindu nationalist demonstrations in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which were characterized by violence, were responsible for the end of the Congress’ hegemony and the ascent of the BJP at the Centre. It is thus paradoxical that they disregard fundamental causes, such as the resistance to the Immigration And nationality act last year and the present Farmers’ Bills, due to the component of violence.

Protests have always been disruptive in our past. Owingowing to the latest farmers’ movement, many others have used the slogan Dilli Chalo (Let’s Go to Delhi). It means that if rulers become accustomed to avoiding difficulties, citizens in sympathy can always go to the seat of power and demand justice.

Blocking highways, closing stores, and causing traffic congestion are sometimes the only ways for a government to listen to citizens because they have real-world consequences. All of these acts come together to make a typical Indian protest – crimson one action to dismiss the more extensive discussion is purposefully ignorant.

Dissent suppression and the erosion of India’s identity

Another concern that comes up frequently is how the system handles dissenters. Many of the laws used to silence critics date back to Colonial times and have remained in place since independence. Protests are as much a part of Indian democracy as the laws that seek to control them.

One of them is the Indian Penal Code’s (Section 124-A) “sedition statute,” which has been interpreted to label dissidents as rebels and imprison them. The British prosecuted Gandhi and Nehru, our first Prime Minister, under the same law and detained them. Under this clause, Disha Ravi, an activist who altered two lines of a document posted by Thunberg to express solidarity with farmers, was also imprisoned. Another statute, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), has been used to imprison dissenters during the present protests.

Protesters and opponents are frequently labelled “Anti-National,” encouraged by a press that is hesitant to criticize the government. As a result, they face social exclusion and, in some circumstances, extrajudicial killings. The use of police harassment and brutality to dissuade protestors is becoming more common. As I write this essay, the prospect of serious ramifications, such as public shaming or police statements, is not out of the realm of possibility.

The Indian experience is incomplete without public demonstrations. They have the capacity to drag politicians to the ground and force them to address our issues; this is a tool of true transparency in the hands of the government. The current leadership has undoubtedly put us on a path that will lead to the end of civil rule in India, assisted by prior failures.

However, if we demonstrate and dissent in an unafraid, unashamed, and unapologetic manner, we may be able to avoid arriving at our goal.

Farmers protesting new farm rules in India burst through police lines around the city on Tuesday, storming the grounds of Delhi’s famous Red Fort in chaotic and violent images that dominated the country’s Republic Day celebrations.

After hundreds of peasants marched on the capital, many on machines or horses, police used batons and tear gas to disperse the gathering. During the clashes, one demonstrator was reported dead, and hundreds of protesters and the police were hurt.

Mobile online services were suspended in various parts of Delhi, and some subway stations were shuttered. Home Minister Amit Shah met with Delhi police to discuss ways to bring the protesters under control as the violence raged into the afternoon. The farmers were enabled to hold a tractor rally as provided as they waited for the formal Republic Day procession to end. However, flag-waving protestors clambered over or shoved aside barriers and concrete blocks on at least four main thoroughfares and continued on into the city.

Agriculture employs almost 40% of India’s population, yet it is a sector rife with poverty and incompetence, with farmers frequently selling their commodities for less than they are worth. India has one of the highest rates of death in the world.

They claim that their problem has been overlooked for decades and that the changes intended to attract capital enterprise into agriculture will merely leave farmers at the whim of big businesses.

The Samyukta Kisan Morcha, which represents over 40 farmer’s unions, criticized individuals who took part in the skirmishes, saying that “anti-social extremists have infiltrated the usually peaceful rally.”

“We condemn and deplore today’s unwanted and unacceptable occurrences, and we distance ourselves from individuals who engage in such acts,” the organization stated in a statement.

Thousands of farmers marched into India’s capital city of Delhi earlier this week in a convoy of tractors to protest the execution of three unpopular farm policies. What was supposed to be a peaceful gathering quickly devolved into fights between farmers and police.

Most people have accused the farmers of beginning the rioting after the tragedy. What occurred on January 26 was not supposed to happen. But that doesn’t change the case that the protests started in the first place.

Farmers had been demonstrating for months, fed up with the government’s indifference to their plight and the threat of corporate exploitation. They remained outside Delhi, on the frontiers, in the freezing weather, hoping to reach an agreement with the government to improve their position.

The farmers’ unification was viewed as the government’s greatest foe. It was critical to dismantling this organization, backed by wealthy farmers from Punjab and Haryana who could afford to take time off work to protest.

The government’s response was part of a bigger political game intended to fracture the movement, with the first stage delegitimizing the movement’s foundation. The government accomplished this by allowing thousands of farmers to march toward the capital city on a day when most government employees were gathered in one place: India’s Republic Day.

In India, protests have persisted and evolved in the face of an unequal society, widespread poverty and crime, apathy, and a slow-moving legal system. Protests have become a method of redressing grievances, legitimizing requests, functioning of multi-cultural democracy, and a form of democracy and free speech in the absence of alternative options.

Protests can be viewed as the expression of the nation’s collective conscience. They are natural and active, changing their shapes, sizes, and objectives on a regular basis. In a pluralistic country like India, clashes between police and protestors are not unusual. Conflict is unavoidable, and citizens frequently march in the streets to deliver vigilante justice and vengeance when the court and state institutions fail.

Farmers’ deaths and droughts (most recently, demonstrations by Tamil Nadu farmers), women’s safety (most notably the Nirbhaya protests, which resulted in criminal law revisions and now the BHU), and miscarriage of justice have all been the subject of demonstrations (which perhaps can be traced to re-trial and sentencing of Manu Sharma in Jessica Lal murder case following public outcry).

Student protests have been met with official repression (in the University of Hyderabad over the suicide of Rohith Vemula, in Jawaharlal Nehru University over the arrest of Kanhaiya Kumar and the disappearance of Najeeb Ahmed, and in the Film and Television Institute of India over the appointment of Gajendra Chauhan). After the self-styled godman Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh was convicted, there were riots in his support of raping two female followers.

In a democracy, moral outrage serve a valuable role. Righteous emails to the editors, furious statements on social media, civil proceedings, police complaints, and frequent protests and marches that vary from peaceful memorial services to rioting and murders are examples of it. Thanks to social media and very healthy networks, organized demonstrations are on the rise in India. This is also taking place at a time when civil freedoms are being curtailed, and dissenting viewpoints are being targeted. Protests, on the other hand, are not usually associated with the ruling class.

Indeed, the poor and marginalized are disproportionately affected by injustice, and they have regularly banded together to bring their situation to light (the Chipko movement led by forest-dwelling women remains a watershed moment in the history of ecological struggles).

India, in reality, has a long history of protests. These can be traced all the way back to independence movements when people began to understand the concept of a nation-state. These have varied from the bloody 1857 revolution to Gandhi’s calm pan-India satyagrahas.

As a result, India has developed new and effective protest methods that, in addition to drawing attention, have symbolic importance (for instance, women hugging the tress to assert their deep bond and dependence on forests, or Dalits dumping cow carcasses in public places to neglect hierarchical and violent caste-based work imposed on them).

Edited by Prakriti Arora