What does the Varanasi court ruling mean for the Kashi Viswanath-Gyanvapi dispute? What happens next?

What does the Varanasi court ruling mean for the Kashi Viswanath-Gyanvapi dispute? What happens next?

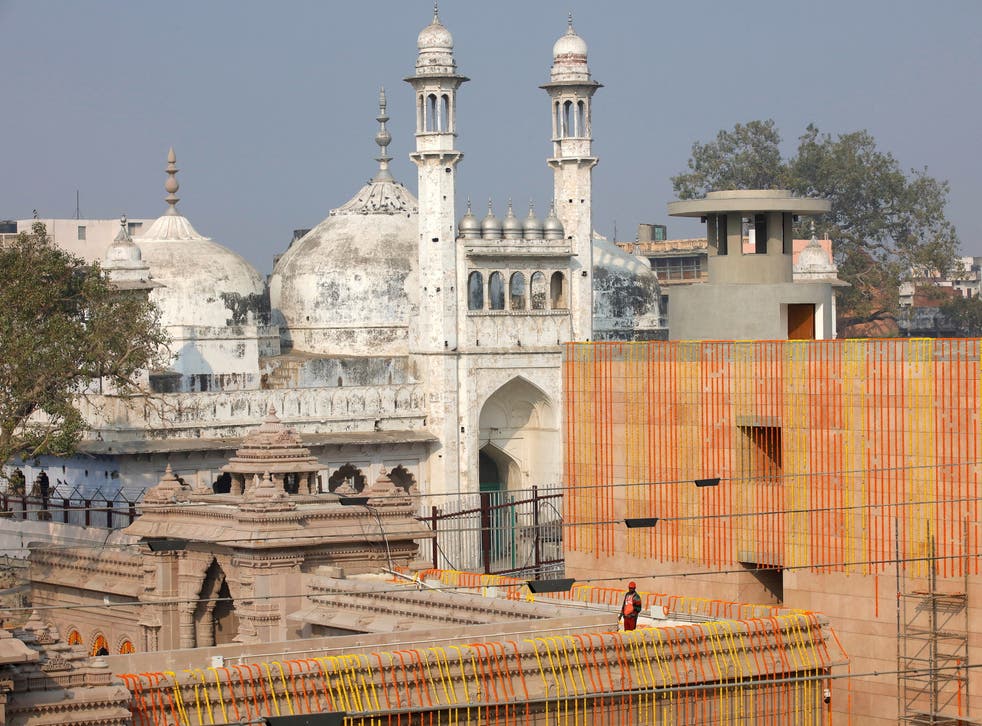

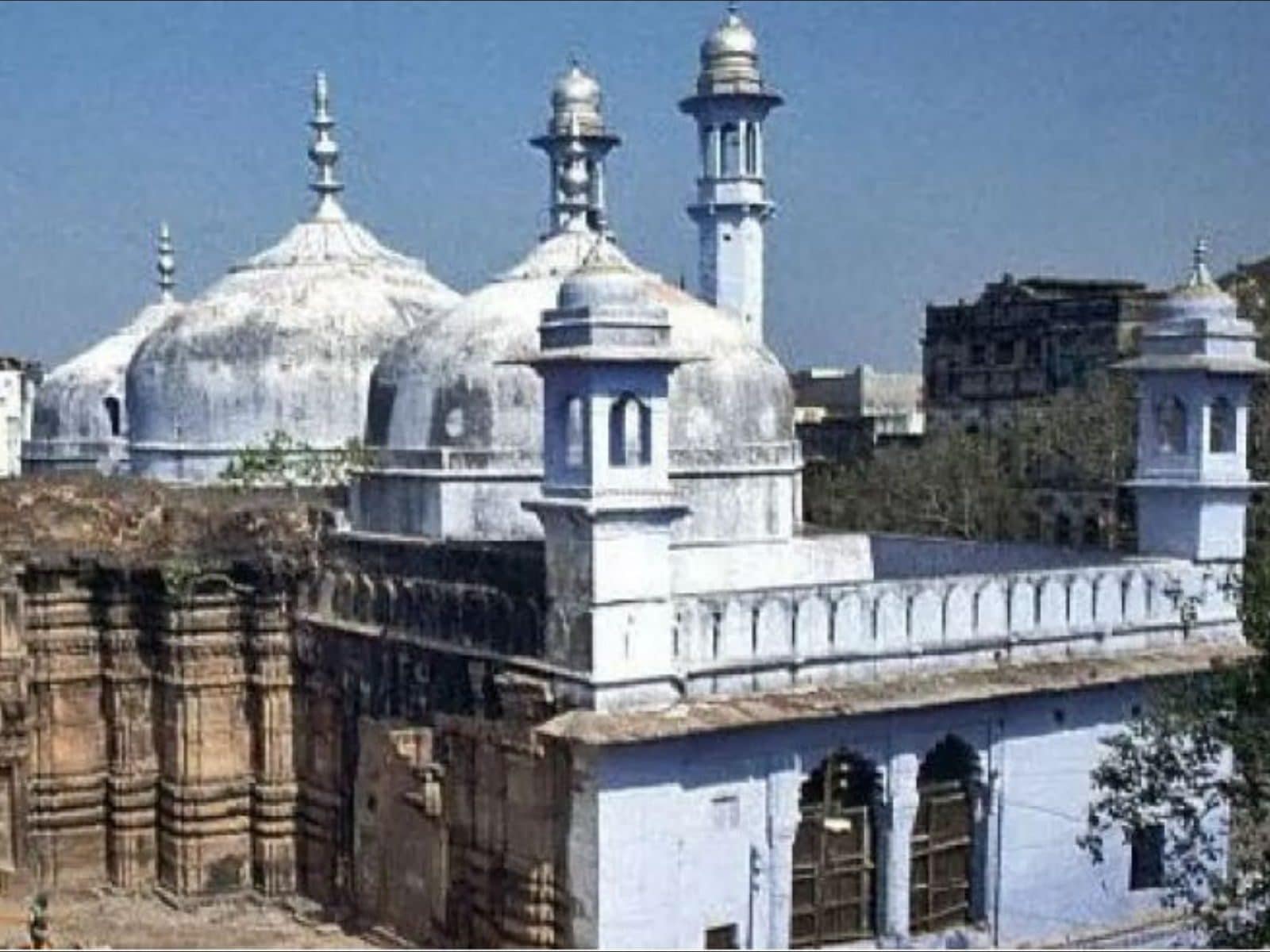

New Delhi: A civil suit seeking the right of Hindus to pray inside the disputed Kashi Vishwanath Temple-Gyanvapi Mosque complex in Varanasi has been heard and concluded by the district court in Varanasi.

The court dismissed an application filed by the Anjuman Intezamia Masjid, the mosque committee in charge of the disputed mosque, challenging the civil suit’s maintainability on Monday.

The original suit, filed in August last year by a Delhi-based woman and four Varanasi-based women, seeks permission to worship the idols of Maa Shringar Gauri, Lord Ganesh, Lord Hanuman, and Nandi within the vexed Kashi Vishwanath Temple-Gyanvapi Mosque complex in Varanasi.

District judge A.K. Vishvesha ruled that the suit is not barred by the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which prohibits changing a place of worship’s religious character from what it was on 15 August 1947. The court ruled in its order that the plaintiffs’ argument “does not hold much water” because they only want the right to worship at the disputed property and do not claim ownership of the mosque.

However, petitions to the Supreme Court challenging the 1991 law are currently pending.

What will occur in district court?

The district court was listening to an application filed under Order 7 Rule 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure, which lists the conditions under which the court can reject a plaint or a plea.

Simply put, it helps to determine whether or not the proceedings in a case can continue and whether or not the court can hear them. The rule states that a plea will be rejected if the relief sought is illegal.

The goal of this provision is to eliminate frivolous litigation in order to save judicial time and resources. In this case, the Anjuman Intezamia Masjid claimed, among other things, that the Places of Worship Act, 1991, barred the suit.

Because the district court has ruled that the suit is maintainable, it will now rule on the plaintiffs’ plea, which is whether they have the right to pray inside the mosque. In fact, the court has already scheduled a hearing on September 22 for the filing of a written statement and the framing of issues. This means that the court will now formulate the issues on which it will rule and hear arguments on them.

What about the Act Concerning Places of Worship?

One of the most important arguments advanced by the mosque committee is that the suit is barred by the Places of Worship Act of 1991.

The law was sanctioned in September 1991, during the first year of the P.V. Narasimha Rao government, a year before the Babri Masjid was demolished, and it has been controversial since then.

Simply put, the law prohibits the conversion of a place of worship, such as a church, mosque, or temple, to another religion’s place of worship. It also states that any court proceedings relating to such conversion would be terminated once the Act takes effect.

The Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute was an exception under the law because it was already the subject of civil suits before the law was enacted.

Several petitions were filed challenging the law’s constitutional validity, including those filed by Ashwini Upadhyay, a lawyer and spokesperson for the Bharatiya Janata Party, and BJP Rajya Sabha Member of Parliament Subramanian Swamy.

Along with these, several independent applications for hearings have been filed by organizations such as Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind.

The Supreme Court has scheduled the petitions for October 11 and has ordered the Centre to respond within two weeks. However, the Supreme Court has not issued a stay of proceedings in the trials and suits brought under the Places of Worship Act of 1991. As a result, all cases, including those involving Gyanvapi, will continue to be heard in courts across the country.

How the case ended up in district court?

The five women — Lakshmi Devi, Sita Sahu, Rekha Pathak, Manju Vyas, and Rakhi Singh — filed the petition on August 18, last year, with the support of the Vishwa Vaidik Sanatan Sangh.

On the day the plea was heard, the Varanasi court appointed an advocate commissioner, Ajay Kumar Mishra, to conduct a survey of the area. A day later, the court ordered that the survey be videotaped.

On April 21, the Allahabad High Court dismissed a challenge to the proceedings in a 14-page decision that made no mention of the 1991 law. The mosque survey began on May 6.

On 13 May, Anjuman Intezamia Masjid filed a petition in the Supreme Court challenging the survey, citing the 1991 law. The Hindu Sena responded by petitioning the court, claiming that the 1991 law does not apply to the Gyanvapi mosque because the Kashi Vishwanath temple and Shringar Gauri temple within the mosque complex are protected by the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958. The monuments covered by the 1958 law are exempt under the 1991 law.

Before the Supreme Court could hear the case, an application was filed before Civil Judge (Senior Division) Ravi Kumar Diwakar, claiming that during the inspection, a Shiva Linga was discovered on the premises of the mosque. On May 16, the judge ordered the Varanasi district magistrate to seal the location where the Shiva Linga was allegedly discovered.

Within days, two reports on the videography survey were submitted to the Varanasi court, claiming that ruins of old temples had been discovered outside the barricade, and Hindu motifs such as bells, Kalash (pitcher), flowers, and Trishul (trident) could be seen on pillars in the tehkhana (basement).

The Supreme Court denied to interfere in the survey on May 20 but transferred the case to a district judge, stating that “a slightly more seasoned and mature hand [should] hear this.”

It requested that the district judge rule on whether the Hindu parties’ suit should be heard on a priority basis. The court also stated that it made this decision with “peace in mind” and to “maintain balance and fraternity between two communities.”

Notably, the Supreme Court stated that the 1991 law only prohibits the conversion of religious places of worship but not the “ascertainment of religious character” of these places.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court heard appeals in July challenging the Allahabad High Court order, which upheld the Varanasi court’s order to appoint an advocate as a court commissioner to inspect the mosque complex. On the other hand, the Supreme court said that it would await the district judge’s decision on the maintainability application and scheduled the case for October 20.

Why was Gyanvapi given its Sanskrit name?

Another unusual feature is the mosque’s unusual name.

Scholars in Varanasi agree that the term ‘Gyanvapi’ arose from the combination of two words: gyan (knowledge) and vapi (water reservoir or a well). Both words are Sanskrit in origin, and the term refers to the “well of knowledge,” which is mentioned in the Skanda Purana (dating from the eighth century CE) and in numerous historical accounts of Kashi (Varanasi)

In his real account, Benaras Illustrated, first published in the 1830s, English scholar and chronicler James Princep did not recognize the name Gyanvapi and referred to the mosque as Aulumgeree (Alamgiri) Masjid.

In addition, the Alamgiri masjid is located in Hartirath Mohalla, approximately two kilometers away from the Gyanvapi mosque. The Dharharewali masjid on the Panchganga ghat is also known by the same name.

According to Ali Nadeem Rezavi, Professor of Medieval History at Aligarh Muslim University, the Alamgiri Masjid, like the Babri Masjid, was named after Mughal ruler Babur. In contrast, the Babri Masjid was named after Mughal ruler Babur (conqueror of the world in Persian). “The Babri Masjid was built by Meer Baqi but named after Babur because it was built during his reign,” he tells ThePrint. “Likewise, the now-Gyanvapi Masjid was named after Aurangzeb, who took the title of Alamgir.”

Kubernath Sukul, a Chronicler, confirms this. “Krittivashewar temple used to stand on the north side of Kal Bhairav temple and of the Vridhkaal (deity),” he writes in Varanasi Vaibhav (2008). Aurangzeb destroyed it in 1659 and replaced it with the Alamgiri Masjid…”

edited and proofread by nikita sharma