UK Census 2021: Why immigration dominates UK politics?

UK Census 2021: Why the immigration dominates UK politics? The most recent data is likely to fuel the fears of those who blame immigration for all of the country’s problems. What narrative does the census data tell? We analyze it.

A number of fascinating demographic trends that have been revealed by the UK’s Census 2021 are likely to have political repercussions in the nation. For instance, Nigel Farage, the main proponent of Brexit, wrote on Twitter that immigration was causing a “massive change in the main identity of this country.”

What is revealed by the most recent census?

In accordance with a press release from the UK’s Office of the National Statistics (ONS), the country’s population at the halfway point of 2020 was predicted to be 67.1 million, up roughly 284,000 (0.4%) from the halfway point of 2019.

What factors contribute to population growth?

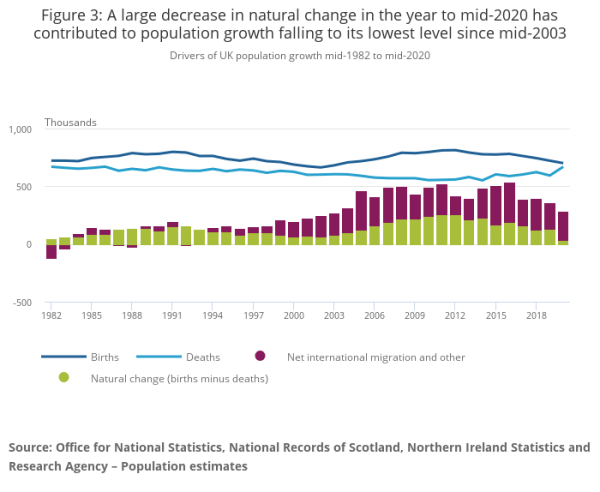

A country’s population is only influenced by the birth rate, death rate, and also net immigration (i.e., net of those entering the country and also those leaving it).

What justifies the focus on immigration?

It is important to note that net immigration contributed to almost 87% of the increase from 2019 to today. We estimate that more than 622,000 people immigrated to the UK while nearly 375,000 people left, for net international migration of 247,000, according to the ONS.

In fact, CHART 1 illustrates the reasons why immigration has evolved over the past three decades into such a divisive political topic. In 1992 or 1993, the birth and death rates in the existing population were different, which is what caused all of the population growth. In 1992, there were more people leaving the UK than entering, which is known as negative net immigration.

However, natural change (green bars) has lost significance in predicting population growth over the past three decades. With each passing year, the net immigration rate has elevated itself to a more important position.

What has happened to religious identities over time?

A majority of current people in England and Wales identify as Christians. But this is no longer the case, as shown in CHART 2.

“Less than half of the population (46.2%, or 27.5 million people) identified as “Christian” for the first time in an England and Wales census, according to the ONS. “This represents a 13.1% decrease from 59.3% (33.3 million) in 2011,” the statement reads.

Despite this drop, “Christian” was still the most frequent response to the religion question. It is important to note that the census’s religion question is optional.

The population who was, however, identified as having “No religion” has seen the biggest increase.

“No religion” was the second most frequently given response. Only 14.1 million people, or 25.2% of the population, declared “no religion” in 2011. This percentage will increase by 12.0 percentage points to more than t37.2% of the population by 2021.

The second-largest increase in population was among Muslims, who increased by more than a million. Numerous other religions experienced a slight uptick, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism.

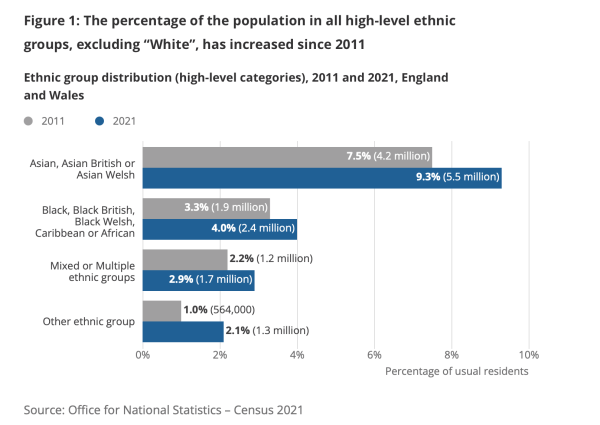

What has ethnic identity development looked like?

The English and Welsh censuses have asked about ethnic groups since 1991. The ethnic group issue is divided into two phases.

A person first declares their affiliation with one of the five high-level ethnic groups listed below:

“Asian, Welsh, and British Asian”

“African, Caribbean, British, Welsh, or Black”

“White,” “Other ethnicity,” “Mixed or Numerous”

The next step is to choose one of the 19 response choices, which include:

Asian, Asian Welsh, Asian British: White or Indian: Irish, mixed, or numerous ethnic groups, such as White and Black Caribbean.

“White” continued to be the most prevalent high-level ethnic group in England and Wales, accounting for 81.7% (or 48.7 million) of usual residents in 2021, down from 86.0% (or 48.2 million) in 2011. In other words, the percentage and absolute numbers of white people have decreased.

The majority of other ethnic groups grew both proportionally and numerically.

The ONS reports that “Asian, Asian British, or Asian Welsh” is the second most prevalent high-level ethnic group, making up 9.3% (5.5 million) of the total population. This ethnic group also experienced the largest percentage point increase from 2011, rising from 7.5% (4.2 million) in 2011.

What does this mean, exactly?

Politics in the UK has been driven by concerns about immigration as well as a pervasive belief, especially among “Whites,” that the UK’s nature and character are changing as a result of such high levels of immigration. This worry, along with other economic worries, was seen as a direct cause of the decision to leave the EU, which surprised many in 2016.

One of the UK’s most influential politicians and the face of the Brexit campaign, Nigel Farage, tweeted the following:

Although The Indian Express was unable to independently confirm all of Farage’s assertions, the information is likely to increase the anxieties of those who believe that immigration is the cause of all of the UK’s problems.

Six years after the Brexit vote, many UK citizens are now openly attributing the country’s current economic woes to that decision. Numerous unbiased analyses indicate that the UK economy has suffered significantly as a direct result of leaving the EU.

Canada is benefiting from immigration. However, the conversation cannot end there.

Ken Coates holds a Canada Research Chair at the University of Saskatchewan, is a Distinguished Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and is the director of the Indigenous affairs program.

Immigration has unquestionably greatly enriched Canada. Waves of immigrants have brought their skills, cultures, and desire for a better life, from French and British explorers to the anticipated expansion of the immigration pool to include 500,000 new arrivals from all over the world annually by 2025.

Canada, like newcomers, adjusted as immigration patterns changed, becoming a stronger but different nation as a result. The already impressive cultural diversity of Canada is thriving and growing. The majority of provinces in Canada, with the exception of Quebec, appear to have an unofficial understanding that immigrants can contribute to resolving pressing labour shortages.

Despite the positive change that migration brings, Canadians all too frequently approach immigration policy — and its corollary, how we make sure immigrants integrate successfully — with a casual attitude.

Given that the government has stated that it will continue to increase the number of immigrants to Canada, it is important to consider how the nation is changing and how policymakers can handle this change deliberately and thoughtfully.

The migration’s scope is breathtaking. An influx of immigrants equal to ten times the population of the Yukon, or about the size of Newfoundland, enters Canada each year. There are nearly as many immigrants arriving every two years as life in Saskatchewan or Nova Scotia.

The demographic and political significance of the country’s smaller jurisdictions, however, significantly declines as our population grows. Canada has developed into a country of city-states, with a few major metropolitan areas dominating the economy and politics and being where most immigrants choose to settle.

First- and second-generation newcomers make up 79.6 percent of the population in the Greater Toronto Area, according to a compilation of 2021 census data by Environics chief demographer Doug Norris; in Vancouver, the percentage is 72.5 percent. These and other large cities help to maintain the Liberal Party’s hold on power and will almost certainly influence the results of upcoming national elections.

The advantages of immigration are dispersed unevenly across Canada’s vast country. Few immigrants are moving to smaller communities, including resource towns threatened by federal antidevelopment policies and the rapid advancement of technology. This lack of immigration is not even close to stopping the steady decline of rural and small-town Canada.

The federal government has declared that it will give immigration to rural and small-town America priority in order to address this. Only a few newcomers will succeed in getting there, though. Many of those who do will probably move to bigger cities later in search of what they perceive to be better job and life opportunities, as well as more numerous cultural and linguistic groups. The need to draw and keep immigrants in those areas must be prioritized.

Canada is fortunate to be regarded as one of the most alluring locations for international migrants, and our immigration policies are well known for giving priority to the admission of people and families who can make the greatest economic contributions to Canada. However, we don’t do much to aid immigrants in assimilating into our society.

New immigrants need assistance with housing, other issues, job searches, credential recognition, language learning, and cultural and political awareness. They will need a lot of resources as their kids enrol in Canada’s public school systems.

Despite the crucial role that non-governmental organisations and intergovernmental cooperation play in facilitating these essential aspects of immigration, policymakers all too frequently brush these worries off as afterthoughts. This is bad for the communities that welcome immigrants as well as for new Canadians.

Due to widespread migration, indigenous peoples are faced with significant difficulties. In Canada, there are about 1.8 million First Nations, Metis, and Inuit people, according to the census taken in 2021. The relative political power of Canada’s first peoples will continue to decline as immigration continues at the current rate, which would equal the entire Indigenous population today.

It makes sense that the majority of immigrants to Canada are ignorant of the people, cultures, histories, and rights of Indigenous communities. Without a concerted effort to address this ignorance, there is a real danger that Indigenous needs and interests will drop further down the list of priorities for the expanding electorate and, consequently, for governments.

Immigration can aid in the change that Canada can and should embrace. But it needs to be done carefully. Our country’s strengths include a number of truly world-class, multicultural cities and a quickly growing service economy, but it also exacerbates current weaknesses. It’s not necessary to be like this. It’s time to have a candid conversation about how to best support immigrants’ success and Canada’s future.

Edited by Prakriti Arora