Turkey’s economic crisis :The Turkish Statistical Institute said that the annual inflation rate for June was 78.62 percent

Turkey’s economic crisis :The Turkish Statistical Institute said that the annual inflation rate for June was 78.62 percent

According to figures released on Monday, the effect of the Ukraine war, rising commodity costs, and a decline in the value of the Lira since a crisis in December all contributed to Turkey’s annual inflation rate reaching a 24-year high of 78.62 percent in June, slightly more than expected.

The Turkish Statistical Institute said that the annual inflation rate for June was 78.62 percent, exceeding expectations.

The 84 million-person population has been severely impacted by rising consumer costs, with little chance for change in the foreseeable future due to the Russia-Ukraine war, high energy and food prices, and a swiftly depreciating lira.

Turkey’s latest month of inflation saw a rise of about 79 percent, the greatest level the country has witnessed in twenty-five years.

The Turkish Statistical Institute said that the annual inflation rate for June was 78.62 percent, exceeding expectations. In 24 years, that represents the highest annual inflation reading for the country. 4.95 percent more money was made each month.

Due to the Russia-Ukraine war, high energy and food costs, and a rapid decline in the value of the Lira, the country’s currency, the 84 million-person population has been heavily struck by rising consumer prices, with little chance for change in the near future.

According to official statistics, the cost of transportation increased by 123.37 percent from the prior year, while the cost of food and non-alcoholic beverages increased by 93.93 percent.

Since the central bank progressively lowered its policy rate by 500 basis points to 14 percent last autumn being a part of an easing cycle aimed at improving economic development, the Lira has fallen, and inflation has risen.

According to the most recent data, consumer prices increased by 4.95 percent in June, vs. a Reuters poll’s prediction of 5.38 percent. Consumer price inflation was expected to reach 78.35 percent annually.

According to figures from the Turkish Statistical Institute (T.U.I.K.), food and non-alcoholic drink prices increased by 93.93 percent and 123.37 percent, respectively, in June, driving up consumer price inflation.

It was the highest annual inflation rate since September 1998, when Turkey was trying to end a decade of protracted high inflation, and annual inflation touched an all-time high of 80.4%. After the statistics, the Lira remained at 16.78 percent.

This year, the economic consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have further fueled inflation.

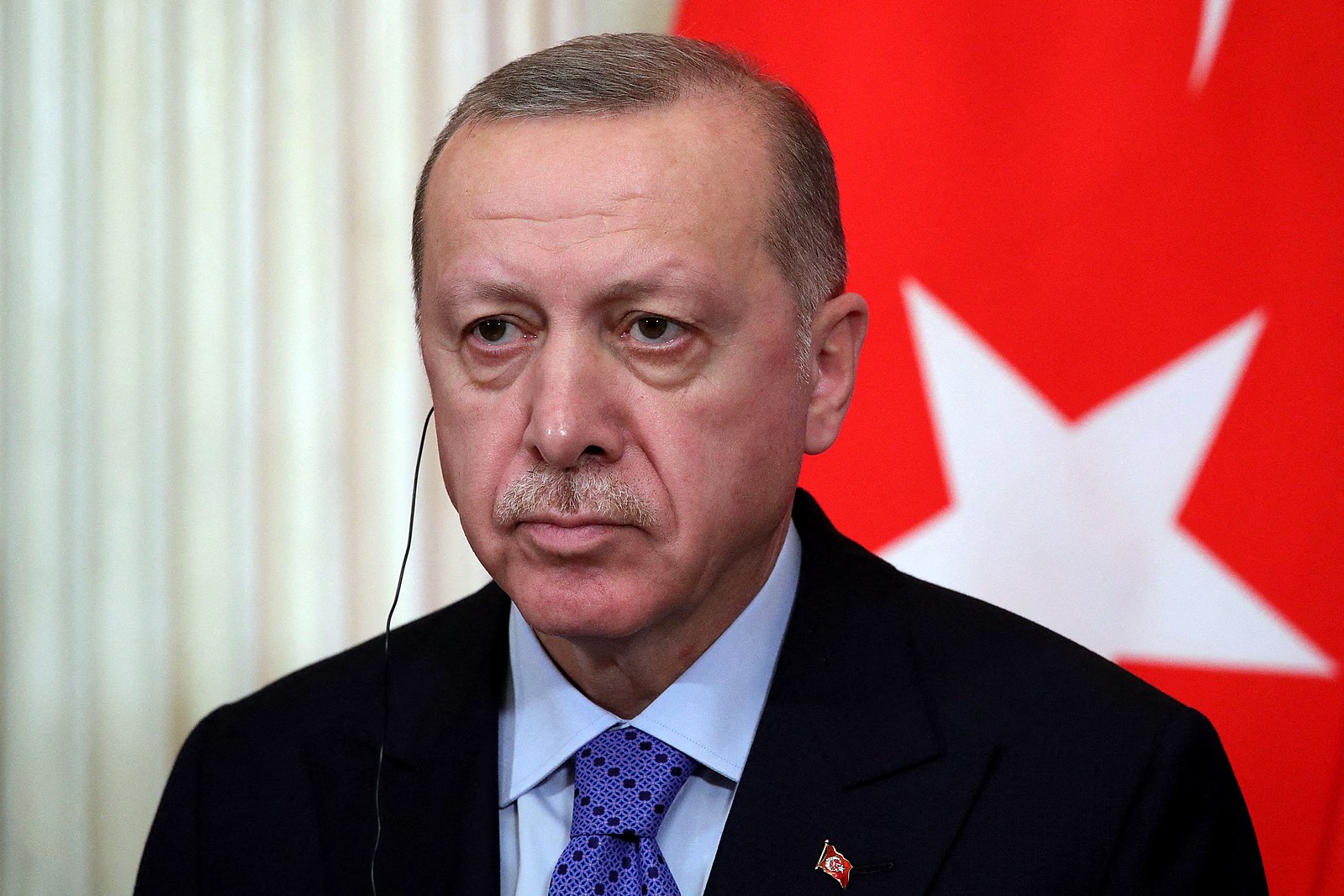

Prior years saw Turkey experience strong development, but President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has, for the past several years, refused to hike rates much to reduce the ensuing inflation, calling interest rates the “mother of all evil.” The outcome has been a falling Turkish lira and majorly reduced purchasing power for the usual Turk.

Erdogan urged the country’s central bank to continually lower borrowing rates in 2020 and 2021 despite inflation continuing to climb. Analysts claim that the central bank lacks independence from Erdogan. Those in charge of the central bank who voiced disagreement with this strategy were sacked; by the spring of 2021, Turkey’s central bank had been led by four different governors.

Last November, the country’s interest rate was progressively lowered to 14 percent, where it has stayed ever since. The Turkish currency lost 44 percent of its value vs. the U.S. dollar last year, and since the year’s beginning, it has lost 21 percent.

The Turkish government has implemented unconventional measures in an effort to support the Lira without improving interest rates.

prohibition on lira loans to businesses holding what the Turkish banking regulator judged to be excessive amounts of foreign currency was announced in late June, which temporarily strengthened the currency but increased investor anxiety about the measure’s long-term viability.

THE TOXIC MIX

Erdogan stated last week that he expects inflation to reach “acceptable” levels by February or March of the next year. The central bank predicted that inflation would fall to 42.8 percent by the end of 2022 while maintaining the benchmark interest rate at 14 percent.

Turkey is “in a league of its own” among emerging markets (E.M.) when it comes to inflation, according to Witold Bahrke, a senior macro strategist at Nordea Asset Management in Denmark, because of what he claimed was its lack of a viable policy response.

ccording to Bahrke, “inflation is a general problem for E.M., and in Turkey, you end up with a poisonous combination since we also have a policy issue,” adding that he anticipated some additional depreciation of the currency.

The validity of the T.U.I.K. statistics has been questioned by economists and opposition M.P.s, which T.U.I.K. has refuted. According to polls, Turks think inflation is far higher than the official statistics indicate.

According to the inflation survey conducted last week, by the end of 2022, inflation was projected to reach slightly around 70%.

In relation to the dollar, the lira currency fell by 44 percent last year and is already down by 21 percent this year.

In June, the domestic producer price index increased 6.77 percent month over month, giving it a 138.31 percent annual increase.

It is yet another depressing milestone for a country whose currency has lost more than 20% of its value against the U.S. dollar since the year’s beginning and has been plagued by widespread inflation in recent months.

Even if President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s unconventional economic tactics have exacerbated the problem and the falling Lira has made imports significantly more costly, Turkey’s economy is nevertheless subject to the same dynamics of global inflation as other nations.

Erdogan broke the rules in September and instructed Turkey’s central bank to begin lowering interest rates rather than raising them as prices rose.

Turkey is doing in complete opposition to what the other central banks of the world are doing, which is raising borrowing costs in an effort to reduce demand and curb inflation. Since December, interest rates have stayed around 14%.

In order to reduce inflation and increase output and exports, Erdogan has defended his monetary policy by claiming that decreasing rates will achieve so. He has attributed foreign meddling to the economic issues facing his nation.

Turkish Economy Minister Nureddin Nebati said in a tweet on Monday that “the continuance of substantial rises in global commodity prices, notably in energy and agricultural items,” were to blame for June’s inflation.

He said that the government was taking steps, such as lowering sales taxes and providing subsidies, to protect citizens from skyrocketing prices.

Erdogan stated last week that his administration would increase the minimum wage by 30% starting this month, barely six months after it was increased by 50%, in order to assist employees with the skyrocketing cost of living.

However, the action may advance the nation closer to a perilous wage-price spiral, which would worsen the situation.

Consumer spending will continue to be affected negatively by inflation and the weak Turkish Lira, according to research released last week by S&P Global Ratings. It anticipates that yearly inflation will be over 20 percent and above 70 percent until at least mid-2023.

The analysis stated that exports, which up until recently were a major economic engine for Turkey, will be negatively impacted by the recession in Russia and Ukraine as well as the slowdown in growth in the U.K. and the eurozone.

This summer, a pick-up in overseas travel may provide some respite by increasing profits in foreign currencies, claims the research. That may help the Lira.

According to official figures released on Friday, Turkey’s annual inflation rate reached 73.5% in May, the highest level since 1998, as the nation’s cost-of-living issue worsens.

According to the Turkish Statistical Institute, the rate increased by about 70% from the previous month. From April, consumer prices increased by over 3%, according to the institute.

While consumer costs are growing in many nations, opponents point the finger of blame at President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s economic policies for Turkey’s woes.

Contrary to conventional economic wisdom, the Turkish leader maintains that high borrowing costs generate inflation and proposes decreasing interest rates to encourage growth and exports.

Since September, Turkey’s central bank has lowered interest rates by five basis points, bringing them to 14% before stopping them in January. Last year, the Turkish Lira lost 44% of its value relative to the U.S. dollar.

The situation in import-dependent Turkey has gotten worse as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which caused a spike in gas, oil, and food prices.

The results from the statistical agency show that the sector with the largest yearly price rises was transportation, at 107.6%, followed by food and non-alcoholic beverage costs, at 91.6%.

Turkey’s Economic Troubles Intensify as Currency Resumes Slide

Turkey has been frantically putting billions of dollars into supporting its currency in an effort to support its economy. The pressure on President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s finances is getting tighter as a result of these policies losing their appeal.

Turkey’s problems have been made worse by Russia’s invasion of the neighboring Ukraine, global inflationary pressures, and a rising currency. The circumstances had made a domestic problem worse that started last year when Mr. Erdogan forced the central bank to lower interest rates amid skyrocketing inflation.

The Turkish consumer and business sectors’ purchasing power was further diminished on Wednesday as the Lira fell for the sixth straight day, reaching 17 lire to the dollar for the first time since the crisis of last year.

Millions of Turkish residents have been driven closer to poverty by the growing costs of food, healthcare, electricity, and other necessities, which has weakened support for Mr. Erdogan’s administration.

The weak currency and Turkey’s unstable financial circumstances provide Mr. Erdogan with an uneasy background. He has emerged as a crucial figure in the conflict in Ukraine, convening conferences on food supplies and cease-fires, supplying drones to Ukraine, and preventing Sweden and Finland from joining NATO.

The economic challenge he faces at home, though, is the most significant since he took office two decades ago, immediately following another economic disaster.

Turkey’s statistics office said on Friday that the country’s inflation rate increased to about 75% in May. The rate is now the highest among G-20 countries and ranks sixth globally, trailing only Syria, which is still embroiled in civil conflict, and Venezuela, a failing state.

According to unaffiliated experts, the inflation rate is probably far higher. Turkey’s genuine inflation rate, according to ENAGroup, an initiative run by economists and accountants, is closer to 160 percent. The Turkish government has taken steps to restrict independent economists’ capacity to disclose inflation data and make statements that they believe may damage Turkey’s currency. The government statistics office sued ENAGroup last year over the company’s inflation estimates.

Contrary to what is taught by conventional economics, the Turkish president has advocated for lower interest rates in the hope that they will boost economic growth and eventually reduce inflation. In late 2021, he compelled the central bank to reduce interest rates four times in a row.

The Lira fell as a result. Turkey used a variety of temporary steps to stabilize the currency for a while. The most notable of them was a scheme at the end of last year that offered to reimburse citizens who retained their savings in Lira at the bank for the difference in the currency’s decline versus the dollar.

These are time-buying measures. According to Erik Meyerson, a senior economist at the Swedish bank Handelsbanken, they are not policies that address economic issues.

However, with inflation skyrocketing, the Lira’s decline has resumed in recent weeks. Since the beginning of the year, it has lost more than 20% of its value.

By using the few remaining dollars at its disposal to intervene in currency markets and support the Lira, the central bank has attempted to halt the decline. The Wall Street Journal’s analysis of central-bank statistics reveals that the bank probably sold $24 billion worth of foreign currency between January and March of this year.

2018–2022 Turkish currency and debt crisis

There is a current financial and economic crisis in Turkey that will last from 2018 to 2022. The Turkish Lira’s (TRY) sharp decline in value, high inflation, growing borrowing costs, and consequently rising loan defaults are its defining characteristics.

The huge current account deficit and significant private debt in foreign currencies, together with President Recep Tayyip Erdoan’s rising authoritarianism and unconventional views on interest rate policy, were the main contributors to the crisis in the Turkish economy. Additionally, some experts emphasize how the geopolitical tensions with the United States may be used.

After the failed coup attempt in Turkey resulted in the imprisonment of American pastor Andrew Brunson on espionage allegations, the Trump administration put pressure on Turkey by imposing further penalties. Due to the economic penalties, import levies on steel and aluminum have increased by up to 50% and 20%, respectively, in Turkey. Turkish steel was thus priced out of the U.S. market, which had previously accounted for 13% of Turkey’s overall steel exports.

While waves of significant currency depreciation were the crisis’ first distinguishing feature, corporate loan defaults and, ultimately, a slowdown in economic development was the crisis’ latter stages. Stagflation resulted from the inflation rate becoming stuck in the double digits.

The crisis put an end to a period of excessive economic expansion under Erdoan’s leadership, which was primarily supported by a construction boom fed by foreign borrowing, readily available cheap credit, and government expenditure.

The Turkish currency fell after the change of Central Bank chairman Naci Abal with ahap Kavcolu, who lowered interest rates from 19 percent [10] to 14 percent, after a period of minor recovery in 2020 and early 2021 amid the COVID-19 epidemic.

[11] In only 2021, the Turkish Lira’s value fell by 44%.

The popularity of Erdoan and the A.K.P. is said to have significantly decreased as a result of the economic crisis; they lost the majority of the country’s largest cities, including Istanbul and Ankara, in the 2019 municipal elections.

Current account deficit and foreign-currency debt

Turkey’s economy has a history of having a low savings rate. Ever since Recep Tayyip Erdoan took over as prime minister, Turkey has been running one of the largest current account deficits in the world, with deficits of $33.1 billion in 2016 and $47.3 billion in 2017, growing to US$7.1 billion in January 2018 and a rolling 12-month deficit of $51.6 billion. Turkey’s banks and major corporations have taken on significant debt, frequently in foreign currencies, in order to finance the private sector excess that has been a major drag on the economy.

With only $85 billion in gross foreign currency reserves, Turkey is forced to find around $200 billion a year to cover its large current account deficit and maturing debt while also constantly risking a drying up of inflows.

Since the victory of his Justice and Development Party (A.K.P.) in 2002, and especially since 2008, Erdoan has increasingly micromanaged the economic policy that underlies these developments, focusing on the construction sector, state-awarded contracts, and stimulus measures. Even though the country’s research and development spending (percent of G.D.P.) and government spending on education (percent of G.D.P.) virtually increased under the A.K.P. regimes, the intended results could not be achieved.

According to the secretary-general of the largest Turkish business organization, TUSIAD, Erdoan’s lack of trust in Western-style capitalism after the 2008 financial crisis is the driving force behind these initiatives. The Turkish assault of Afrin, while not directly connected to the war, significantly harmed US-Turkish ties and increased instability in Syria. Turkish aggression is perceived as needless as a result.

An enormous backlog of unsold new homes and unprofitable large-scale projects, such as the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge, whose operator is guaranteed 135k passenger car-equivalent of daily toll revenue, resulted from fiscal and monetary stimulus to the construction industry that had previously driven economic growth.

Due to Erdoan inciting political disputes with nations that were important sources of such inflows, investment inflows had already been falling in the years before the crisis (such as Germany, France, and the Netherlands). The government confiscated the assets of people it said were involved in the 2016 coup attempt, notwithstanding the fact that their involvement had diminished.

Concerns that international businesses investing in Turkey would be discouraged by the nation’s political volatility have not been taken seriously by Erdoan. Concerns over the Lira’s (TRY) declining value, which might reduce investors’ profit margins, are another issue. Additionally, the rise in authoritarianism under Erdoan has stifled independent and truthful reporting by financial experts in Turkey, which has decreased investment inflows.

The most recent figures available show that between January and May 2017, foreign portfolio investors paid for $13.2 billion of Turkey’s $17.5 billion current account deficit. They only managed to close $763 million of a ballooning $27.3 billion deficit over the same time in 2018.

After deducting their foreign exchange assets, Turkey’s corporate foreign currency debt by the end of 2017 had increased by more than twofold since 2009, reaching $214 billion. Turkey’s total external debt, public and private, was $453.2 billion at that time. As of March 2018, $181.8 billion of that debt, public and private, was set to mature within the next 12 months.

In early March, non-residents held $53.3 billion in domestic shares, which had dropped to $39.6 billion by mid-May, and $32.0 billion in domestic government bonds, which had increased to $24.7 billion. As of July 13, 2018, there was just $53 billion in total non-resident ownership of Turkish stocks, government bonds, and corporate debt, down from a peak of $92 billion in August 2017.

‘Action plans’ for the government to deal with the situation

To combat the current financial crisis, the Turkish government’s finance minister, Albayrak, launched a new economic plan. “Reign in inflation, promote growth, and reduce the current account deficit” is the three-year plan’s stated goal.

The proposal calls for a $10 billion cut in government spending as well as the suspension of projects whose tenders have not yet been completed. By 2021, two million new jobs should have been created thanks to the transformative phase of the plan, which will concentrate on value-added sectors to boost the nation’s export volume and long-term production capability.

According to the program, economic growth will likely decline sharply in the medium term (from an earlier prediction of 5.5 percent to 3.8 percent in 2018 and 2.3 percent in 2019), but it will gradually pick up the pace by 2021 and reach 5 percent.

Intervention by the president with the central bank

In comparison to other developing economies, Turkey’s inflation rate has been significantly higher.

The greatest rate of inflation since July 2008 was 11.9 percent in October 2017. The exchange rate of the Lira continued to decline in 2018, hitting levels of 4.0 TRY per USD by late March, 4.5 TRY per USD by mid-May, 5.0 TRY per USD by early August, and both 6.0 and 7.0 TRY per USD by mid-August. The rapid value decline was mostly ascribed by economists to Recep Tayyip Erdoan’s efforts to stop the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey from adjusting interest rates.

In a May 14 interview with Bloomberg, Erdoan, who previously described interest rates as “the mother and father of all evil,” shared unconventional interest rate views and asserted that “the central bank can’t assume this independence and leave aside the signals sent by the president.”

International investment circles generally believe that Turkey is experiencing a “textbook institutional decline,” with Erdoan increasingly seen as dependent on politicians whose main qualification for their positions is loyalty, at the expense of more qualified and experienced alternatives. This perception is what led to the president’s intervention with central bank policy.

Additionally, Erdoan has a long history of criticizing interest-based banking as “prohibited by Islam” and “a significant dead-end” in Islamist discourse.

Erdogan has also been quoted as calling for interest rate rises “treasonDespite his resistance, Turkey’s Central Bank raised interest rates significantly.

Leading emerging markets financial analyst Timothy Ash was quoted by The Financial Times as saying, “Turkey has strong banks, healthy public finances, good demographics, and a pro-business culture but [has been] spoiled over the past four to five years by unorthodox and loose macroeconomic management.”

By mid-June, analysts in London suggested that Turkey would be wise to apply for an I.M.F. loan under its current government even before the country’s central bank’s resources began to wane.

Paul Krugman, an economist, defined the issue as “At such a time, the quality of leadership suddenly matters a great deal,” the speaker said, describing the situation as “a classic currency-and-debt crisis, of the sort we’ve seen many times.” You need decision-makers who are aware of what’s going on, capable of coming up with a solution, and credible enough for markets to give them the benefit of the doubt.

These are present in several emerging markets, and they are handling the upheaval rather effectively. The Erdoan administration lacks all of that.”

Turkey’s repercussions

One of the primary factors contributing to the crisis, according to some, is Recep Tayyip Erdoan’s unconventional views on interest rates.

Lenders in Turkey were impacted by restructuring requests from businesses that were unable to pay their USD or E.U.R. debt due to the decline in the value of their profits in the Turkish Lira at the time the crisis first emerged. Despite accounting for about half of the value of the Istanbul stock exchange for many years, financial institutions had decreased to less than one-third by mid-April.

By the end of May, lenders were dealing with an increase in demand from businesses looking to restructure debt repayments. Early in July, public restructuring requests from some of the largest companies in the nation had amassed a total of $20,000,000,000, with other debtors either not publicly listed or not of a size requiring disclosures.

Throughout the crisis, both the capital adequacy ratio and the asset quality of Turkish banks continued to decline most susceptible of the major institutions, Halk Bankas, had lost 63 percent of its U.S. dollar value since last summer and was trading at 40 percent of book value at the end of the year.

The valuation of Halkbank was significantly impacted by speculations regarding the potential results of the U.S. investigation into the bank’s alleged assistance to Iran in evading U.S. sanctions. Therefore, it is difficult to argue that this is primarily attributable to Turkish economic trends.

Banks constantly raised interest rates on home loans, consumer loans, and business loans, pushing them up to 20% yearly and reducing demand from both firms and individuals.

The disparity between total deposits and total loans, which had been one of the largest in developing economies, started to close as deposits increased in tandem with this trend. However, as a result of Erdoan’s policies, the building industry—where many of his corporate associates are heavily active—was fueled to drive past economic growth, resulting in unfinished or vacant houses and commercial real estate dotting the outskirts of Turkey’s main cities.

When compared to the same month last year, house sales plummeted 14%, and mortgage sales dropped 35% in March 2018. Around 2,000,000 unsold homes were still on the market in Turkey as of May, which is three times the typical annual volume of new home sales.

While the supply of unsold new homes continued to grow in the first half of 2018, Turkey’s new house price hikes lagged behind consumer price inflation by more than 10%.

While significant portfolio capital outflows continued, totaling $883,000,000 in June, and official foreign currency reserves decreased by $6,990,000,000 in that month, the current account deficit began to reduce in June as a result of the weaker lira exchange rate. This was viewed as an indication that the economy was becoming more balanced. As of September 2018, the Turkish Lira began to recoup its losses, and the current account deficit continued to decrease.

Any newly discovered shaky short-term macroeconomic stability is based on increasing interest rates as a result of the previous monetary policy of loose money, which has a recessionary effect on the Turkish economy.

The Washington Post quoted a top finance official in Istanbul in mid-June, saying that “The Turkish economy has overheated as a result of years of reckless practices. Current account deficits and high inflation rates will become problematic. We may have reached the end of our options.”

Suicides

A worker set himself on fire in front of the legislature in January 2018.

In the Hatay governor’s office, another guy also set himself ablaze.

Four siblings were discovered dead in an apartment in Fatih, Istanbul, in November 2019. They had killed themselves as a result of being unable to pay their debts. In 2019, the cost of power rose by over 57%, while the young unemployment rate was about 27%. The apartment’s electricity bill had not been paid in a number of months.

In Antalya, a four-person family with kids aged 9 and 5 was also discovered. The family’s financial woes were described in a message that was left behind.

The Guardian reported in mid-November that after the suicides, an unidentified benefactor had paid off some debts at neighborhood grocery stores in Tuzla and left envelopes of cash on doorstops.

Officials of the AK Parti and the media have refuted the claim that the recent fatalities were brought on by the growing expense of living.

Likewise, take a look at the ties between Turkey and the European Union, and the United States.

There is a significant risk of financial contagion as a result of the crisis. According to the Bank for International Settlements, foreign banks owed Turkish borrowers a total of $224 billion in outstanding loans, including $13 billion from Germany, $83 billion from Spain, $35 billion from France, $18 billion from Italy, and $17 billion from each of the United States and the United Kingdom. The danger to foreign lenders is one component of this.

Another issue relates to the state of other developing nations with significant debt in USD or E.U.R., with Turkey potentially serving as “a canary in the coalmine” or worsening the situation by driving away foreign investors due to their heightened sense of risk in such nations.

The Institute of Financial Research (I.I.F.) claimed on May 31, 2018, that South Africa, Colombia, and Lebanon have already been affected by the Turkish crisis. The residents of northern Syria, who depend on the Lira for daily transactions, have also been left in poverty, and the hazelnut sector, which is crucial to the nation’s economy and supplies 70 percent of the world’s hazelnuts, has been severely harmed.

Politics and corruption

The Turkish government claims that a foreign scheme is underway

The Turkish administration of Erdoan and the A.K.P. has a lengthy history of spreading conspiracies; therefore, Members of the administration have claimed that the financial crisis was not caused by the actions of the government but rather was the result of a plot by unknown foreign players who wished to hurt Turkey and weaken President Erdoan.

During the big currency sell-off on May 23, 2018, Turkey’s energy minister, Erdoğan’s son-in-law Berat Albayrak, informed the media that the recent dramatic decline in the value of the Lira was the product of the manipulations of Turkey’s adversaries.

On May 30, 2018, Mevlüt Avuşolu, Turkey’s foreign minister, claimed that a coordinated effort planned from overseas was to blame for the Lira’s decline. He added that the conspiracy would involve “the interest rate lobby” as well as “certain Muslim nations,” but he declined to name them.

On June 11, 2018, Erdoan said that the 7.4% G.D.P. growth number for the period of January to March would show triumph over what he dubbed “conspirators,” who he blamed for the Turkish Lira’s sharp declines in May, at a campaign rally in Istanbul. Erdoan first used the phrase “the world conducting an economic war against Turkey” in August.

This concept perhaps sprang in part from a disagreement with America over the situation involving American citizen Andrew Brunson, which harmed Turkey-U.S. ties. Both nations utilized tariffs as well as sanctions against certain government officials to exert economic pressure. It is referred to as a “trade spat” by Vox. Commentators have emphasized the significance of Brunson’s case, including Jen Kirby of Vox.

The United States imposed a tax on Turkey for steel and other goods. Although only the sanctions will be dropped upon Brunson’s release, Sarah Sanders has stated that the American tariffs are tied to “national defense” and, as such, cannot be altered by external factors.

These taxes, according to Erdogan, are an “economic war” on Turkey.

Turkey retaliated by announcing duties on American goods, including the iPhone.

The tariffs imposed by Turkey apply to goods like coal and American autos. These were referred to as “regrettable” by Sanders at a White House press briefing. According to Sanders, the economic problems in Turkey are a result of a long-term trend and are unrelated to anything the United States accomplished.

The Turkish government made a big mistake by not releasing Pastor Brunson, according to John R. Bolton, who was speaking to Reuters on August 22. “Every day that goes by that mistake continues, this crisis could be over instantly if they did the right thing like a NATO ally, part of the West, and release pastor Brunson without conditions,” he added.

He continued by saying that the U.S. was less concerned about Turkey’s NATO membership and that it was more concerned about the people Turkey was allegedly keeping for illegitimate purposes. Bolton raised doubt about Qatar’s efforts to inject cash into the Turkish economy. In a written statement, Erdogan spokesperson Ibrahim Kalin characterized these comments as an admission, in contrast to Sanders, that the American tariffs were, in fact, related to the Brunson issue and evidence that the U.S. intended to wage economic warfare against Turkey.

A survey conducted in April 2018 found that 42 percent of Turks and 59 percent of supporters of Erdoan’s A.K.P. government believed that foreign governments were behind the Lira’s collapse. In a separate July study, 42% of participants believed foreign countries were to blame for the weakening of the Turkish Lira, compared to 36% who blamed the A.K.P. administration.

This was attributed to the government’s extensive media control since respondents who read alternative viewpoints online often were more probable to hold their own government accountable (at 47%) than did foreign governments (at 34%).

Muharrem nce and Meral Akşener made a commitment to re-establish the credibility of Turkey’s financial institutions.

On May 7, presidential candidate and head of the Y Party Meral Akşener unveiled her economic platform.

Crisis like a campaign issue in June 2018

Republican People’s Party (C.H.P.) presidential candidate On May 16, a day after president Erdoan alarmed markets during his visit to London by implying he would limit the independence of the Central Bank of Turkey after the election, Muharremnce and Y Party presidential candidate Meral Akşener both pledged to ensure the central bank’s independence if elected.

C.H.P. presidential candidate Muharrem nce discussed the economic policy in a May 26 campaign interview “Since devaluation does not fundamentally result from either too high or too low-interest rates, the central bank can only temporarily stop the Lira’s decline by improving rates.

Therefore, the central bank will step in, but the political and legal spheres are where genuine action is required. A political environment in Turkey that creates economic uncertainty has to be swiftly removed, and its economy needs to be managed by independent and autonomous institutions. My team of economists is prepared, and we have been collaborating for a while.”

In a countrywide poll conducted between May 13 and 20, 45 percent of respondents cited the economy (especially the gradually depreciating currency and unemployment) like Turkey’s biggest concern, followed by foreign policy (18%), the judicial system (7%) and terrorism and security (5%)

The Y Party’s presidential candidate Meral Akşener said on May 7 that, with the aid of a strong economic team headed by former Central Bank Governor Durmuş Yilmaz, “we will purchase the debts from consumer loans, credit card and overdraft accounts of 4.5 million citizens whose debts are under the legal supervision of banks or consumer financing companies and whose debts have been sold to collection companies as of April 30, 2018.”

As the government has aided major corporations in challenging circumstances, it is our responsibility to assist our countrymen with this condition.”

On June 13, C.H.P. leader Kemal Klçdarolu reiterated the opposition’s contention that Turkey’s currency, investment, and economy are being hindered by the state of emergency that has been in place since July 2016. He vowed that, should the opposition win the elections, the emergency would be lifted within 48 hours.

While C.H.P. presidential candidate nce made the following pledge on May 30, Y Party leader and presidential candidate Akşener made the identical promise on May 18 “Foreign nations do not invest in Turkey because they do not trust it.

Foreign investors will invest in Turkey after it establishes itself like a country of the rule of law, increasing the value of the Lira. In an interview in early June, President Recep Tayyip Erdoan had said that the topic of abolishing the emergency rule would be considered after the elections, but in response, he had questioned: “What’s wrong with the state of emergency?”

edited and proofread by nikita sharma