Top 8 Cases that are Unsolved by CBI

The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) is India’s top agency for looking into crimes. The Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances, and Pensions are in charge of its work. It was initially set up to look into bribery and corruption in government. In 1965, it was given more power to look into violations of central laws enforced by the Government of India, multi-state organized crime, and international or multi-agency cases.

Some economic crimes, specific crimes, cases of corruption, and other cases have been looked into by the agency. The Right to Information Act does not apply to the CBI. CBI is India’s official single point of contact with Interpol.

Establishment for Special Police

The Special Police Establishment (SPE), a Central Government Police force, was set up in 1941 by the Government of India to look into bribery and corruption in transactions with the War and Supply Department of India. This is where the Bureau of Investigation got its start.

Its main office was in Lahore. Qurban Ali Khan was in charge of the SPE, but he later chose to live in Pakistan during the Partition of India.

Rai Sahib Karam Chand Jain was the first lawyer who worked for the War Department. Even after the war, a central government agency still needed to look into bribery and corruption by central government employees. The 1946 Delhi Special Police Establishment Act moved the department to the Home Department, but Sahib Karam Chand Jain stayed on as its lawyer.

All of the Government of India’s departments are now included in the DSPE’s work. It had power over the Union Territories, and it could also have control over the states if the governments of those states agreed. Sardar Patel, the First Vice Prime Minister of free India and head of the Home Department, wanted to eliminate corruption in places like Jodhpur, Rewa, and Tonk, which used to be princely states.

Patel told Legal Advisor Karam Chand Jain to watch the criminal cases against the dewans and chief ministers of those states. The popular name for the DSPE now, “Central Bureau of Investigation,” came from a decision made by the Home Ministry on April 1, 1963.

CBI takes shape

The CBI became known as India’s top agency for investigating crimes. It had the resources to handle complex cases, and it was asked to help investigate crimes like murder, kidnapping, and terrorism. Based on petitions from wronged people, the Supreme Court and several High Courts in the country also started giving these kinds of investigations to the CBI.

In 1987, the CBI was split into the Anti-Corruption Division, the Special Crimes Division, the Economic Offences Division, the Policy and International Police Cooperation Division, the Administration Division, the Directorate of Prosecution, and the Central Forensic Science Laboratory Division.

A Director, an IPS officer with the rank of Director General of Police, is in charge of the CBI. The director is chosen by a high-level committee set up by The Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act, 1946, as changed by The Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, 2013. The director’s term is two years (can be extended for another three years).

Other positions in the CBI that an IRS officer or an IPS officer may fill are Special Director, Additional Director, Joint Director, Deputy Inspector General of Police, Senior Superintendent of Police, Superintendent of Police, Additional Superintendent of Police, Deputy Superintendent of Police, and Additional Deputy Superintendent of Police.

In addition, inspectors, Sub-Inspectors, Assistant Sub-Inspectors, Head Constables, and Constables are hired through the SSC or the Police, Income Tax Department, and Customs Department.

The CBI Director is chosen for a term of at least two years by the Appointment Committee based on the advice of the Selection Committee. This is written in the DSPE Act of 1946, which was changed by the Lokpal and Lokayukta Act of 2013 and the CVC Act of 2003. The members of the Appointments Committee are:

Prime Minister – Chairperson Leader of Opposition of Loksabha or Leader of the single largest opposition party in the Lok Sabha, if the former is not present due to lack of mandated strength in the Lok Sabha – member

Chief Justice of India or a Supreme Court Judge suggested by the Chief Justice – member

When making suggestions, the committee considers what the outgoing director has to say.

Under the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act of 1946, the Selection Committee sends a list of names to the Appointment Committee. The Appointment Committee then chooses one of those names to be the CBI director. The members of the Selection Committee are:

Central Vigilance Commissioner Chairperson Vigilance Commissioners Members Secretary to the Government of India in charge of the Ministry of Home Affairs in the Central Government Members Secretary, Co-ordination and Public Grievances, Cabinet Secretariat Member NDA government, on November 25 2014, moved an amendment bill to get rid of the requirement of quorum in high-profile committee while recommending names for the post of director CBI to the central government.

And to replace the LOP with the leader of the largest single opposition party or a pre-election coalition since the LOP position in the Loksabha is empty as of 2019.

Infrastructure

The CBI’s 11-story, 186 crores ($24 million) building in New Delhi is home to all of the agency’s branches. The 7,000-square-meter (75,000-square-foot) building has a modern communications system, an advanced system for keeping records, space for storage, computerized access control, and a separate room for new technology. In addition, there are rooms for questioning, cells, dorms, and conference rooms.

The building has a cafeteria for staff with space for 500 people, gyms, a terrace garden, and parking for 470 cars on two levels in the basement. There is also a press briefing room, a media lounge, and advanced fire control and backup power systems.

In 1996, the CBI Academy opened in Ghaziabad, in Uttar Pradesh and was east of Delhi.

It is about 40 kilometres (25 miles) from the New Delhi train station and about 65 kilometres (40 miles) from Indira Gandhi International Airport. The administrative, academic, hostel, and residential buildings are all on the 26.5-acre (10.7 ha) campus, with fields and plants.

Before the Academy was built, short in-service courses were held at a small training centre in New Delhi called Lok Nayak Bhawan. The CBI then used state police training schools and the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Police Academy in Hyderabad to teach deputy superintendents of police, sub-inspectors, and constables the basics of their jobs.

All CBI ranks can get the training they need at the Academy. In addition, state police, central police organizations (CPOs), public-sector vigilance organizations, bank and government departments, and the Indian Armed Forces can also participate in specialized courses.

Jurisdiction, powers, and limits

The DSPE Act of 1946 gives the Delhi Special Police Establishment (CBI) and officers of the Union Territories the rights, duties, privileges, and responsibilities that they need to do their jobs. If the government of the state in question agrees, the central government can give the CBI investigation powers and jurisdiction over any area (except Union Territories). Officers in charge of police stations could be CBI members with at least the rank of sub-inspector. Under the act, the CBI can only look into something if the central government tells them to.

In 2022, the Minister of State in the Prime Minister’s office told Rajya Sabha in response to a question that nine states had stopped letting the CBI investigate cases in those states. West Bengal, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Kerala, and Punjab are some states.

Getting along with the state police

The CBI was first created by the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act so that it could work in Delhi. However, under the structure of Indian federalism, police and law are the responsibility of each state. This means that the CBI needs permission from other state governments before investigating their territory.

This permission can be given in the form of a “general consent” under Section 6 of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, which is suitable for all investigations until revoked, or a “specific consent,” which permits to investigate in a single case. Once permission is given, the CBI can look into financial, bribery, and other particular crimes (including national security, drugs and narcotics, etc.)

Most Indian states had given the CBI general permission to look into crimes on their land. But as of 2020, several states have taken away their “general consent” for the CBI to work. Instead, they require special consent for each case. In November 2018, the governments of Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal took away the CBI’s general permission to investigate.

They also said that the Central Government was using federal agencies to make state politics unstable. In 2019, Andhra Pradesh brought back general consent. In January 2019, Chhattisgarh also pulled out of the CBI’s widespread support.

In July 2020, Rajasthan took back its permission for the CBI to do its job. In October 2020, Maharashtra took away its consent for the CBI to work in the state. In November 2020, the conditions of Kerala, Jharkhand, and Punjab pulled out of the CBI.

Tripura and Mizoram had already pulled out of the CBI’s general consent. So as of November 2021, the CBI will need permission from eight states before it can investigate crimes in those states. Meghalaya pulled out of the CBI on March 4, 2022, making it the ninth state.

These killings shocked the whole country, and the people who did them haven’t been caught yet.

1. Noida Double Murder Case – 2008

The Noida double murder case is about the unsolved killings of a 13-year-old girl named Aarushi Talwar and a 45-year-old man named Hemraj Banjade, who worked for her family as a live-in domestic worker. The two people died at Aarushi’s home in Noida, India, on May 15–16, 2008. This story was all over the news. Because people wanted to know who did it. Many people said that the sensational media coverage, which included sleazy claims about Aarushi and the suspects, was like a trial by the media.

When Aarushi’s body was found on May 16, Hemraj, who was missing, was thought to be the person who was most likely to have done it. The next day, Hemraj’s body, which had started to break down, was found on the terrace. The police got a lot of flak for not securing the crime scene right away.

After ruling out the family’s former housekeepers, the police focused on Aarushi’s parents, Dr Rajesh Talwar and Dr Nupur Talwar. The police thought Rajesh killed the two because he found them in an “objectionable” position or because Rajesh’s alleged extramarital affair had led Hemraj to blackmail him and Aarushi into fighting with him.

The accusations upset the Talwars’ family and friends, who said the police set them up to cover up the mess of an investigation they had done. The case was then given to the CBI, which cleared the parents and pointed the finger at Krishna Thadarai, who worked for the Talwars, and Rajkumar and Vijay Mandal, who worked for them at home.

The CBI thought that the three men had killed Aarushi after trying to sexually assault her and Hemraj because he was a witness. This was based on the “narco” interrogation of the three men. The CBI was accused of using shady tactics to get a confession, and all three men were set free when the agency couldn’t find enough evidence to keep them in jail.

In 2009, the CBI gave the investigation to a new team, which said the case should be closed because it was missing important pieces of evidence. Rajesh Talwar was the only person named as a suspect, but he wasn’t charged because there wasn’t enough hard evidence. The parents were against the closure report and said that the CBI’s suspicions about Rajesh Talwar were unfounded.

After that, a special CBI court disagreed with the CBI’s claim that there wasn’t enough evidence and gave the Talwars a court date. In November 2013, the parents were found guilty and given life sentences, but many people said that the evidence was not strong enough to support the verdict. The Talwars went to the Allahabad High Court to fight the decision.

On October 12, 2017, the court found the evidence against them unsatisfactory and found that the police, CBI, and media had not done an excellent job investigating the murder. On March 8, 2018, the CBI went to the Supreme Court to protest the acquittal. Unfortunately, the case hasn’t been solved yet.

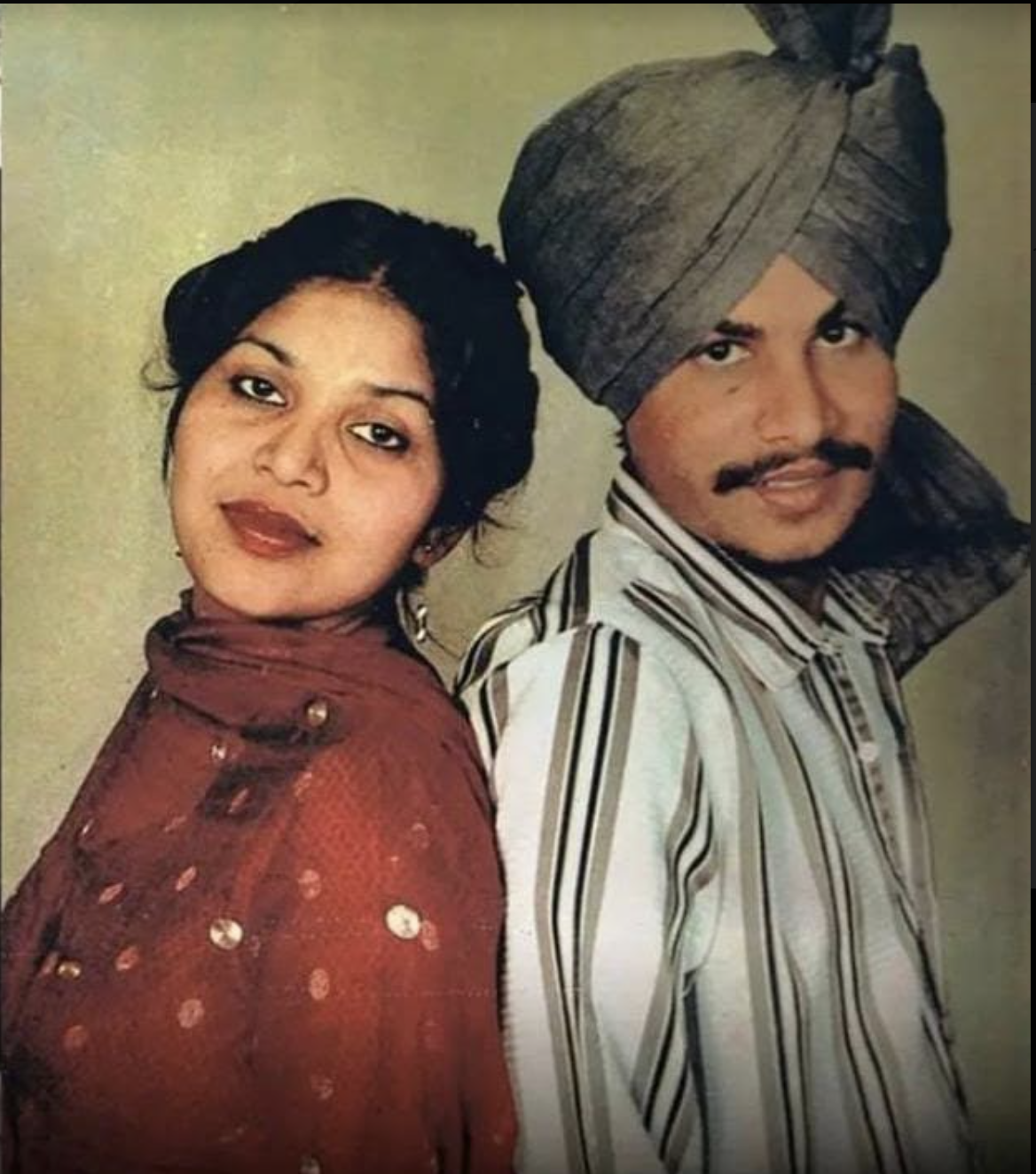

2. Amar Singh Chamkila – 1988

Amar Singh Chamkila was a well-known singer, musician, songwriter, and composer from Punjab. Chamkila, his wife Amarjot, and two other members of their band were killed on March 8, 1988, in a case that hasn’t been solved yet.

People in the village (pind) think that Amar Singh Chamkila is one of the best live performers Punjab has ever had. He is also very popular with the village audience. Almost every month, he had more appointments than days in the month.

His music was heavily influenced by how people lived in the Punjabi village where he grew up. He often wrote songs about relationships outside of marriage, coming of age, drinking, drug use, and Punjabi men’s short tempers. He got a reputation for being controversial because some people thought his music was offensive, and others thought it was a true reflection of Punjabi culture and society.

3. The Chennai Train Bombing happened in 2014.

The 2014 Chennai train bombing happened when two small bombs went off in a train from Bangalore to Guwahati as it arrived at the Chennai Central railway station early on May 1, 2014. One woman was killed, and at least fourteen others were hurt.

4. De La Haye Scandal – 1919

The De La Haye scandal was a big scandal that happened in 1919 in Madras, India, which is now called Chennai. It led to the death of De La Haye, the head of a college in Madras called Newington House, on the night of October 15, 1919, and to a trial with a lot of attention called the De La Haye murder case or the Madras murder case. However, no one was charged, and the case was never solved.

5. Murder of Snehal Gaware

The murder of Snehal Gaware happened in 2007. Snehal Gaware, who lived in Dombivili, Thane, Maharashtra, India, was killed on July 20, 2007. Her boyfriend is thought to have done it. Gawande went to the Sardar Patel College of Engineering in Andheri to learn about engineering. She lived with her parents in Dombivili at the Ninad Society, where she was healing from a leg injury she got in June 2007. However, when her mother came home on July 20, 2007, she wasn’t there. The next day, Gaware’s body was found in the drawer of her bed with her mouth tied shut and her hands and legs tied together.

In April 2010, Hiten Rathod, Gaware’s boyfriend, was arrested and charged with her murder. In the meantime, he had gone to school in the United States. The police dropped the charges the following year because they didn’t have enough proof.

6. Lakshmikanthan Murder Case – 1944

The Lakshmikanthan murder case was a high-profile criminal trial from November 1944 to April 1947 in what was then called the Madras Presidency. A Tamil film journalist named C. N. Lakshmikanthan was killed, which led to the trial. On November 7, 1944, Lakshmikanthan was stabbed in Vepery, Madras.

He died at General Hospital in Madras the following day. Someone was charged with a crime, and several suspects were taken into custody. Tamil movie stars M. K. Thyagaraja Bhagavathar and N. S. Krishnan and director S. M. Sriramulu Naidu were among the suspects.

Naidu was found not guilty, but Bhagavathar and Krishnan were found guilty and sentenced to prison. Bhagavathar and Krishnan went to the Madras High Court to ask for help, but their requests were denied. The two people stayed in jail until 1947 when they won an appeal to the Privy Council. The Council told the sessions court to start over with a new trial. They were found not guilty and set free. The real killers were never found, so the case is still unsolved.

Bhagavathar lost all hope after being arrested. He lost all of his money and was poor when he died in 1959. After that, Krishnan made a few more movies, but not all of them did well.

7. Chandrashekhar Prasad – 1997

Chandrashekar Prasad, who died on March 31, 1997, was a student leader and later an activist with the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation. He was born on September 20, 1964, and died on March 31, 1997. He went to Jawaharlal Nehru University and got a degree there. He was president of the Jawaharlal Nehru University Students’ Union for two terms. Prasad was an essential part of how the All India Students Association came to be.

On March 31, 1997, sharpshooters working for Mohammad Shahabuddin of the Rashtriya Janata Dal killed him as he spoke in support of a strike at a street corner meeting in the district town of Siwan, Bihar. When he was killed, students all over India held powerful demonstrations. As a result, four people were given life sentences in 2012 for killing him. They were all former members of the Janata Dal, which later split into the Janata Dal (United) and the Rashtriya Janata Dal.

8. Murder of Hukum Singh

Murder of Hukum Singh was published in 1984. Raja Hukum Singh Rathore, who died on April 17, 1984, was the son of Maharaja Hanwant Singh, the ruler of Jodhpur, and actress Zubeida Begum. He was born on August 2, 1951, and died on April 17, 1984. Maharaja Gaj Singh, who took over the throne from his father, was Hukum Singh’s stepbrother.

On April 17, 1984, Hukum Singh’s body was found with more than 20 wounds. He had killed himself with his sword. At least three different stories can be told about what happened.

The official story is that he drank whiskey with four or five other men, got angry, and was killed with his sword. On the other hand, it is said that he was sleeping peacefully in a charpoy in the garden of his official residence when he was violently attacked by people who did not know him.

Lastly, he was unhappy with his property and his place in the family. Before he died, he met with his stepbrother Maharaja Gaj Singh. In his autobiography, My Passage from India, Ismail Merchant says that he and Gaj Singh were at a dinner ceremony at the Umaid Bhawan Palace when Hukum Singh rushed in with a sword and was killed by a group of people. Merchant and his publishers were sued for libel, and Merchant later said that the passage was written with “tongue firmly in cheek.”

A suspect named Guman Singh was taken into custody, but he went missing before his trial. So the murder is still a mystery.