Why is the approval of the first malaria vaccine a watershed moment in the fight against parasitic killers?

Malaria made 241 million people sick and killed about 627,000. People who lived in sub-Saharan Africa, where 95% of the cases and deaths happened, mainly consisted of children under five, making up about 80% of the deaths.

The numbers are so bad, but there is finally a reason to be optimistic about things. It was approved by the World Health Organization last October. The vaccine is called RTS, S, or Mosquirix. Plasmodium is a parasite that causes a deadly disease called malaria, and it can be spread to people by mosquitoes that have been infected with the parasite. The world’s first vaccine for malaria has been made. While that’s going on, BioNTech, the German biotech company that worked with Pfizer to make a vaccine based on mRNA, wants to start testing a malaria vaccine in 2022. The tide may finally be going our way.

There will be a massive spread of Mosquirix across Africa now that the WHO has approved it. It’s also the first vaccine for any parasite, which means that the fight against malaria and dozens of other tropical diseases has come a long way since this vaccine came out. People infected with parasitic worms are thought to number more than 2 billion.

Microbiologists have been trying for years to make vaccines that would stop people from getting infections or getting them again. Even though there are treatments for many cases, they haven’t worked. The success of the malaria vaccine shows that it’s possible to get rid of malaria.

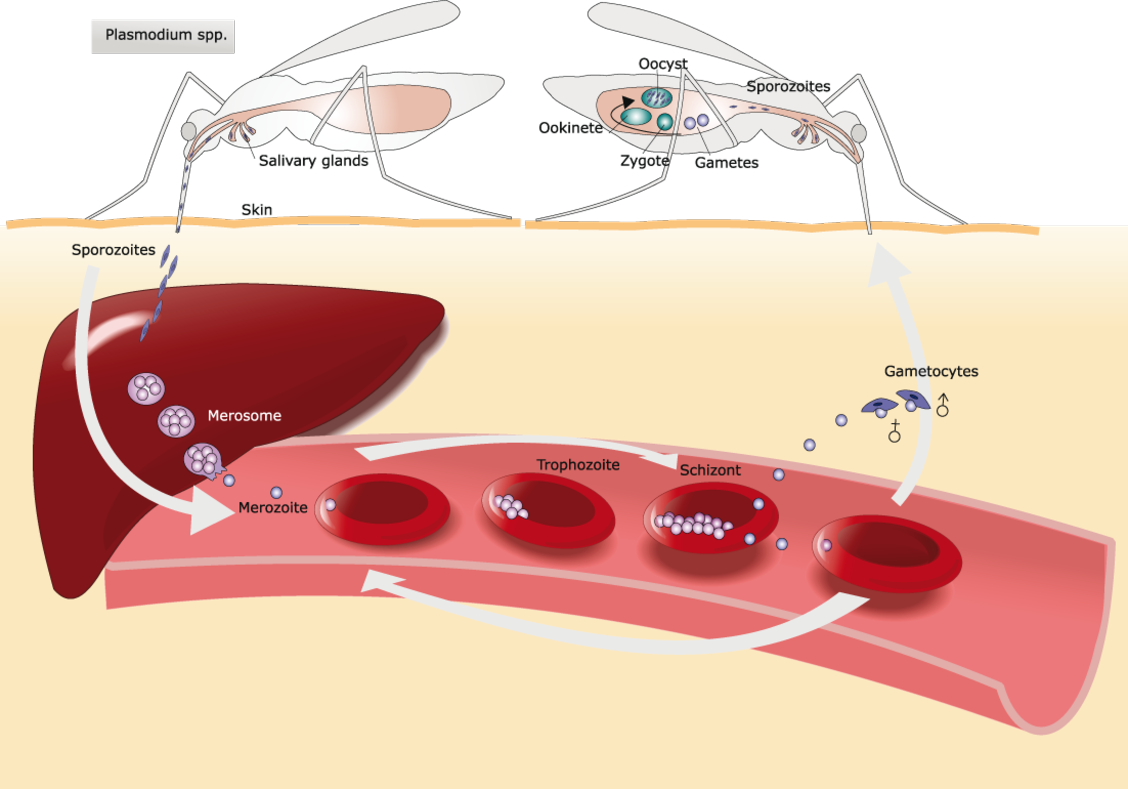

They are tiny animals with many cells, like parasites. Most viruses and single-celled pathogens have genomes 500 to 1,000 times bigger than parasites. This allows them to change in many different ways when an immune response attacks them. It’s perfect in disguise, and malaria is one of the best. On its surface, it can show any one of 60 different proteins, switching them up as needed to avoid being found by the immune system.

Photini Sinnis, the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute deputy director, says we’re dealing with evolution’s best hit. She says these things know us better than we know ourselves, and they know how to do what they need to do. And they have a big enough genome to change our immune system so that they can live in us.

The latest malaria vaccine, which has been in tests since 1987, doesn’t work very well.

Some 800,000 kids in Kenya, Malawi, and Ghana tried it out, and it didn’t work very well in the first year. Over time, it became less effective at preventing malaria. A three-dose regimen of the polio vaccine, on the other hand, protects 99 percent of people from getting the disease. It isn’t very effective once the parasite has set up shop in the body’s blood cells, so the vaccine needs to kill it quickly after infection to be effective.

Still, scientists think they’ve found a way to use it that will be worth it. This drug needs to be given three times between the ages of five and 17 months, and a fourth dose is given 12 to 15 months after the third dose. A clinical study found that when combined with existing malaria control measures, like insecticide-treated bed nets and preventative drugs given during the rainy season, the regimen could cut malaria deaths by about 70%, compared to children who had only been given existing preventive drugs.

An immunologist at Harvard’s school of public health and a malaria expert, Dyann Wirth, says that “it’s going to save lives.” “And it will encourage the research community and the people who fund research to keep coming up with new ideas.”

A strange mixture

A vaccine used to work this way: It exposed people to a pathogen that wasn’t strong enough to make them sick but strong enough to make the body build up defenses against it.

People who tried to use this method with the malaria parasite in the past were slowed down by how hard it was to grow the parasite in a lab and a lot of other logistical issues, says Sinnis. During the 1980s, researchers began to look into what was then an entirely new way to make a malaria vaccine: one that didn’t need the whole parasite but just a tiny part of it.

Scientists found the proteins on the surface of the malaria parasite right after it enters the human body. These proteins were targets for the immune system to attack. They found that they would need to add more ingredients to improve the immune response.

Choosing these additional immune-stimulating components, known as adjuvants, and putting them together with the malaria proteins was a difficult scientific task. Some immunologists think that the body’s immune system has a lot of safety mechanisms to keep it from attacking things that aren’t important or that aren’t harmful.

They came up with something unusual in the 1990s. A team made it from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and SmithKline Beecham Biologicals, which would become part of GlaxoSmithKline. It has copies of a single protein on the parasite’s surface in its early stages, and the protein is linked to a surface antigen for the hepatitis B virus.

This is then mixed with adjuvants, which include a substance from the bark of a rare Chilean tree and a lipid molecule from salmonella bacteria that has been cleaned up. The lipid molecule is so toxic that it makes the immune system go “wacko,” says Sinnis. Other parts of the Mosquirix mix are still unknown.

This weird drink seemed to work

New England Journal of Medicine published a study in 1997 that looked at a tiny group of people. In the study, scientists from Walter Reed and GSK showed that the vaccine worked for six of seven people exposed to the parasite after they got it. Some of the results were good, but it took a decade to test the vaccine’s safety in kids and find out if it worked in young kids who lived in areas where malaria was common. In 2009, about 15,000 kids from seven African countries started taking part in a human study.

It was clear from the results of that study, which ended in 2014, that the vaccine worked. But some of the girls who got it had bacterial meningitis, and there was also a slight rise in the number of girls who died of other things. Some people are afraid that more problems would be seen if the vaccine was used on a massive scale in sub-Saharan Africa.

European regulators’ “positive scientific opinion” means they think the World Health Organization should approve the vaccine. Many of the world’s most prominent philanthropic groups seek advice before agreeing to help fund mass vaccination efforts. People at the WHO asked for more proof of its benefits and a better look at how feasible it would be for a vaccine regimen to reach communities in sub-Saharan Africa, which doesn’t have the same kind of medical and transportation infrastructure as many developed countries.

Those results started a four-dose schedule for children five months old and older in Kenya, Malawi, and Ghana, which began in 2019. The project’s vast scope put an end to any fears about safety, and as a whole, severe malaria was reduced by 30%. The inoculation plan could easily use the public health infrastructure for vaccinations against other childhood diseases, like measles.

You can’t stay hidden for long

Some people at Harvard say that the approval of Mosquirix has sent a strong message to the investors and foundations that most scientists rely on to help them find even better vaccines against malaria and other parasitic diseases. There are also signs of early success in science, which is good.

Jeffrey Bethony and David Diemert, microbiologists at George Washington University in Washington, DC, have used the same techniques to make a vaccine for schistosomiasis. This parasitic disease affects about 190 million people worldwide and is especially common in sub-Saharan Africa. The vaccine is in phase II trials in Uganda (the worms can also cause anemia, stunting, and less ability to learn in children).

Covid-19 vaccines have worked well, which could be a good sign for the new malaria vaccine being worked on by BioNTech. Like the organization’s covid vaccine, this malaria vaccine uses synthetic messenger RNA, which are single-stranded molecules taken up by human cells and start the body’s molecular machinery by making copies of proteins on the pathogen’s surface that are completely harmless.

This vaccine also works by exposing the body to synthetic messenger RNA. These harmless proteins then set alarms in the body’s immune system, causing it to build up an army of immune cells that can recognize and fight off the real thing.

NIH expert on vaccines and malaria, Robert Seder, says that “it’s clear there is a lot that can be done to improve the [GSK] vaccine.” Over the first few years of a child’s life, the goal is for vaccines to protect them better.

The malaria parasite has a lot of different life stages, and each one looks different to the body’s defenses.

Mosquitoes inject many copies of the parasite into the skin. They then travel through the blood vessels and reach the liver, where a small number of parasites live inside cells. Parasites start to grow inside the body. They move into blood cells, eat hemoglobin, and then spread out. They produce so quickly that the blood cell bursts, releasing an army that can infect many more blood cells.

It’s the early stage that the new GSK vaccine tries to get rid of, not the old one. However, once the parasite is inside the blood cells, it’s evolved to be the best it can be to stay alive.

Getting rid of malaria isn’t easy, especially in the later stages of the parasite’s life cycle. This clever parasite that has caused us so much human pain will finally be found. As modern molecular biology techniques get better, there’s finally a reason to believe that this clever parasite won’t be able to hide from us forever.