Taiwan is the new Saudi Arabia, and semiconductors are the new oil.

When China periodically threatens “a war against Taiwan,” one financial analyst questioned Mark Liu, chairman of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), last summer. CEOs are accustomed to being grilled on profit margins and capital expenditures. More grave issues are being faced by executives at the biggest semiconductor manufacturer in the world, which supplies electricity to phones, laptops, and data centers.

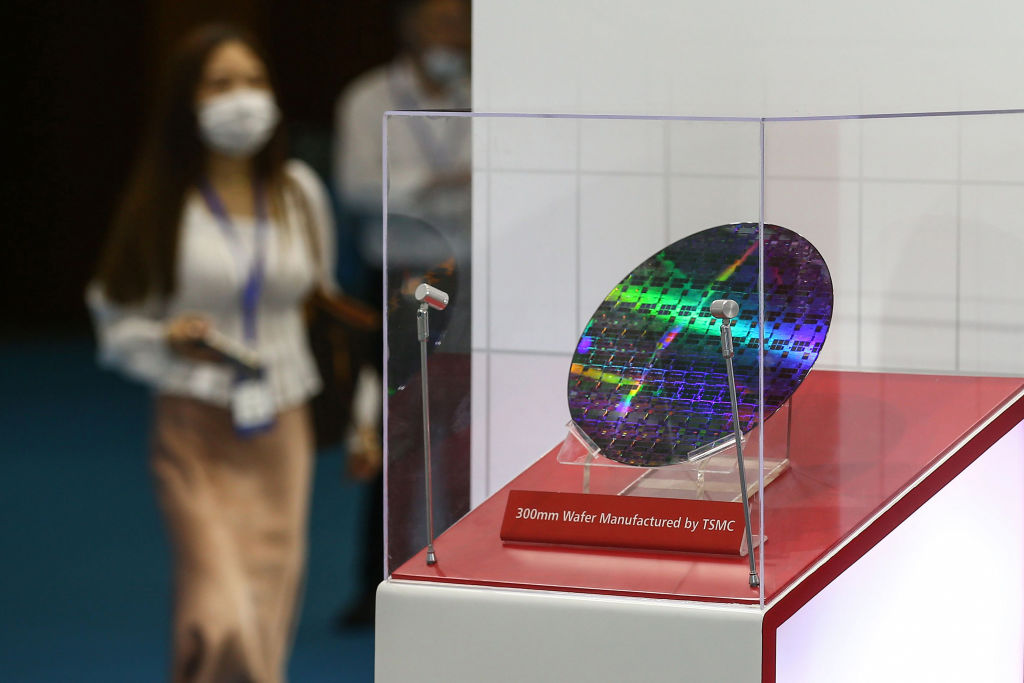

Countless billions of nanometer-sized transistors are patterned onto silicon wafers to produce advanced processors, using expensive equipment, complex software, explosive chemicals, and ultra-pure silicon. For the last five years, TSMC has held the top position in the world thanks to the invention of top-secret processes by its engineers that enable them to shape chips with unparalleled scale and amazing accuracy.![]()

TSMC has over 55% of the global market share for contract chip manufacture, compared to OPEC’s 40% market share for oil. Additionally, unlike the oil market, where every barrel is roughly the same, there are substantial differences between various types of chips. Taiwan produces almost all of the most advanced processors, making Saudi Arabia’s 12% share of global oil production seem ludicrous. Over a third of the new computing power we consume each year is produced in Taiwan.

As a result, TSMC is currently one of the most valuable companies in the world. Additionally, it has rendered the whole world’s digital infrastructure dependent on a little island that the United States has sworn to militarily defend while China considers a renegade province.The risk has increased as TSMC’s importance to the world economy has grown.

Even investors who had for years chosen to overlook the escalating tensions between the United States and China started to scan the map of TSMC’s chip factories located around the western Taiwan Strait with apprehension. The chairman of TSMC is adamant that there is nothing to worry about.Everyone wants a calm Taiwan Strait; he said in 2021, “As for the invasion of China, let me tell you that.” Liu, a Taipei native with degrees from Berkeley and Bell Labs, has an unblemished track record in chip manufacturing.

However, he hasn’t yet been put to the test in terms of estimating the probability of conflict. Given that the globe depends on “the semiconductor supply chain in Taiwan,” he claimed that maintaining peace in the Taiwan Strait is in every country’s interest. Nobody wants to interfere with it.

The automotive chip shortage that caused portions of 2021 and 2022 to see a freeze in the production of new cars has been the focus of the semiconductor shortage debate in the U.S. However, throughout the epidemic, global chip companies generated more semiconductors—8% more in 2020 and 20% more in 2021.

The deficit was caused by increased demand, not a lack of supply. However, it’s easy to imagine situations in which the supply of semiconductors may run out. The day after TSMC’s Liu predicted a “quiet Taiwan Strait,” dozens of People’s Liberation Army Type 05 amphibious armored vehicles sped off the Chinese coast and into the water.

These vehicles, which resemble tanks, may also be used to speed over the ocean like little boats and drive on beaches. Any PLA amphibious attack would greatly benefit from them. Dozens of these vehicles entered the ocean, drove up onto landing ships that were stationed offshore, and then prepared for “a long-distance sea crossing,” according to Chinese official media.![]()

The landing ships made their way to their destination. Wide doors in the ships’ bows opened as they approached, and a torrent of amphibious vehicles poured into the sea, moving to the beach and firing their weapons as they went. This time, it was only a workout.

The PLA conducted further maneuvers close to the north and south Taiwan Strait entrances throughout the following several days. One battalion commander was reported in China’s Global Times newspaper as stating, “We must train hard under conditions that are exactly like those in actual conflicts, be combat-ready at all times, and staunchly preserve national sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

China responded to Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August of this year with a similar round of military drills. Multiple ways China may employ force against Taiwan have been outlined in the Pentagon’s published reports on Chinese military strength.

The easiest—but least likely—is a D-Day-style assault, in which hundreds of Chinese ships stream over the Strait and land tens of thousands of PLA infantrymen on the coastline. However, given the failure rates of previous amphibious invasions, the Pentagon believe that such an operation would “stretch” the PLA’s capabilities.

The PLA could more easily implement other solutions. Taiwan would be unable to overcome a partial air and marine embargo on its own. Without even putting Chinese troops on the ground, a Chinese air and missile campaign by itself could weaken Taiwan’s military and cripple its economy.

This is true even in the absence of a blockade. Without prompt assistance from the United States and Japan, Chinese air and missile forces could certainly disarm important Taiwanese military facilities—such as airfields, radar stations, communications centers, and the like—within a few days without impairing the island’s ability to produce. No one wants to “disrupt” the supply chains for semiconductors that span the Taiwan Strait, as stated by the chairman of TSMC. But everyone wants to have control over them.

The notion that China would merely destroy TSMC’s facilities out of spite is absurd because China would suffer equally with everyone else, especially given that the United States and its allies would still have access to other advanced semiconductor manufacturing in the United States, South Korea, and Europe. Furthermore, it has never been plausible for the Chinese military to enter TSMC’s facilities and take direct control of them.

They would quickly learn that imports from the United States, Japan, and other nations were necessary to get necessary materials and software upgrades for irreplaceable instruments. Furthermore, it’s improbable that China would seize every worker at TSMC if it invaded.

If China did, a few irate engineers would be enough to undermine the entire project. On the disputed boundary between the two nations, the PLA has demonstrated its ability to conquer Himalayan peaks from India, but seizing the most sophisticated industries with the most sophisticated technology is a whole other story.

However, it’s easy to see how a mishap, like a ship or air collision, may turn into a devastating conflict that neither side desires. It is also very conceivable that China would conclude that military pressure short of an invasion might severely undercut American assurances of Taiwan’s security and demoralize the island nation.

Beijing is aware that Taiwan’s defensive plan is to battle until the United States and Japan can arrive and assist. There is no practical alternative besides relying on friends because the island is so small in comparison to the powerhouse across the strait. Imagine Beijing using its fleet to force customs inspections on a small percentage of the ships entering and leaving Taipei.

How would the US react to this? Although a blockade is a kind of hostility, nobody would wish to open fire. The U.S.’s inaction might have a fatal effect on Taiwan’s willingness to fight. Even if such a course of action would be dangerous for Beijing, it is not impossible. The ruling party in China has made several commitments to seize control of Taiwan.

An “Anti-Secession Law” was approved by the government, which foresees the potential employment of what it terms “non-peaceful methods” in the Taiwan Strait. It has made significant investments in the kinds of military equipment required for a cross-strait invasion, notably amphibious assault vehicles. It frequently makes use of these skills.

The military balance in the Taiwan Strait has altered in China’s favor, according to all analysts. The days when the U.S. could simply navigate an entire aircraft carrier battle group across the Taiwan Strait to compel Beijing to withdraw, as it did during the Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1996, are long gone.

The American battleships would be at risk during such an operation. Chinese missiles now pose a danger to bases in Japan and Guam, in addition to U.S. ships near Taiwan. As the PLA develops, the possibility that the US will risk going to war to protect Taiwan reduces. It’s more likely than ever that the United States will analyze the balance of forces and determine that blocking China’s limited military pressure campaign on Taiwan isn’t worth the risk.

The U.S. and Japan would undoubtedly retaliate by imposing new restrictions on the export of advanced machinery and materials, which are largely produced in these two nations and their European allies, if China were to be successful in pressuring Taiwan into granting Beijing equal access—or even preferential access—to TSMC’s fabs. We would still rely on Taiwan for the time it would take to replicate its chip-making capabilities in other nations.If that were the case, China wouldn’t be the only place where our iPhones were put together.

Beijing could be able to obtain influence over or control over the factories that have the scientific and manufacturing capacity to produce the semiconductors we rely on.A situation like this would be terrible for the economic and geopolitical standing of the United States. Even worse would be if the TSMC factories were destroyed in a battle. This tenuous peace is the foundation of the global economy and the supply linkages that span Asia and the Taiwan Strait. From Apple to Huawei to TSMC, any business that has investments on either side of the Taiwan Strait is tacitly placing a bet on peace.

Trillions of dollars are invested in companies and infrastructure in Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Fujian, and Taipei, all of which are within easy missile range of the Taiwan Strait. The Taiwan Strait and the South China Coast are more important to the world’s chip industry than any other region outside of Silicon Valley for the assembly of all the electronic products that chips make possible.

In the tech capital of California, normal business operations are not nearly as dangerous. In the event of a war or earthquake, the majority of Silicon Valley’s knowledge could be readily moved. This was put to the test during the epidemic, when the majority of the local workforce was instructed to stay at home. Profits at large IT companies even increased. Facebook might not even notice if its opulent headquarters were to slide into the San Andreas Fault.The Chelungpu Fault, whose movement triggered Taiwan’s most recent major earthquake in 1999, might be breached by TSMC’s fabrication facilities, with devastating consequences for the world economy.

A small number of intentional or unintentional explosions might be sufficient to do significant damage.The COVID-related semiconductor scarcity served as a timely reminder that chips are used in more than just computers and phones. Products of many kinds, including automobiles, microwaves, and manufacturing machinery, would experience disastrous delays.

For new fabs to be constructed elsewhere, almost one-third of PC processor production, including chips made by Apple and AMD, would be halted. Particularly for servers devoted to AI algorithms, which are more dependent on Taiwan-produced processors from firms like Nvidia and AMD, growth in data center capacity would drastically slow down.

The impact on other data infrastructure would be greater.For example, new 5G radio equipment needs processors from a variety of companies, many of which are based in Taiwan. The spread of 5G networks would virtually come to an end. It would be logical to put a stop to mobile phone network improvements since it would be very challenging to purchase a new phone as well.

The majority of smartphone CPUs and many of the other dozen or so chips included in a typical phone are produced in Taiwan.We would have considerably worse delays than the shortages of 2021 since cars can require hundreds of chips to function. Of course, we’d have to consider much more than chips if a conflict broke out.

A cutoff might occur in China’s extensive electronics manufacturing infrastructure. Any phones or laptops we have parts for would need to be put together by someone else.Since it would be extremely difficult to get a new phone, it would make sense to halt making upgrades to the mobile phone network.

Most of the other dozen or so chips included in a normal phone, as well as the bulk of smartphone CPUs, are made in Taiwan. Since automobiles might require hundreds of chips to function, we would have even greater delays than the shortages of 2021. Of course, if a war broke out, we’d have to think about far more than chips. China’s huge electronics manufacturing infrastructure may see a shutdown.

Any phones or computers for which we have parts would require assembly by a third party.Both ASML and Applied Materials revealed during the 2021 chip crisis that they were having trouble creating gear because they couldn’t get enough semiconductors. They would have difficulties obtaining the chips their apparatus needs in the event of a Taiwan crisis.The entire cost of the semiconductor shortage following a catastrophe in Taiwan would be in the billions. The annual loss of a third of our computer capacity may be more expensive than the COVID outbreak and its economically devastating lockdowns. Rebuilding the lost chip-making capability would take at least five years.

Today, we want to be creating 5G networks and metaverses five years from now, but if Taiwan were to be brought offline, we could find ourselves unable to buy dishwashers.In a recent article for Foreign Affairs, Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, said that the island’s chip sector serves as a “silicon shield” that enables Taiwan to protect itself and others against aggressive attempts by authoritarian governments to disrupt global supply chains.

As a result, the outlook for the situation is favorable. The United States is plainly more concerned with Taiwan’s defense because of the island’s chip sector.However, if the “silicon shield” fails to deter China, Taiwan’s concentration of the semiconductor industry poses a threat to the global economy. One Chinese government expert recently stated publicly, when assessing the role of semiconductors in the Russia-Ukraine War, that if tensions between the United States and China escalate, “we must take TSMC.

“Nowadays, the American-Chinese rivalry is usually described as a second Cold War. Of course, the Cold War had its standoffs over Taiwan when Mao Zedong’s forces blasted Taiwanese-held islands with artillery in 1954 and again in 1958. Today, Taiwan is within striking distance of a variety of short- and medium-range missiles, as well as aircraft, from the Longtian and Huian airbases on the Chinese side of the Taiwan Strait, from which it is just a seven-minute flight to Taiwan. It should come as no surprise that these airfields got modifications in 2021, such as larger bunkers, longer runways, and missile defenses.

A fresh Taiwan Strait crisis would be more dangerous than the 1950s conflicts. The potential for a nuclear battle would still exist, especially in light of China’s growing nuclear arsenal. But this time, instead of taking place over a barren island, the war would occur in the core of the digital world. And to make matters worse, unlike in the 1950s, it is uncertain if the People’s Liberation Army will finally give in. Beijing could wager that this time it stands a strong chance of winning.