The most significant US action against China is the semiconductor exports crackdown.

The visit to Taiwan by Nancy Pelosi in August made front-page news all around the world and sparked fears of a full-scale war between the United States and China. At the beginning of the month, the Biden administration took far more drastic measures against China, yet it attracted relatively little attention in Australia. Biden decided to blatantly deny China access to modern computer chips (aka semiconductors).

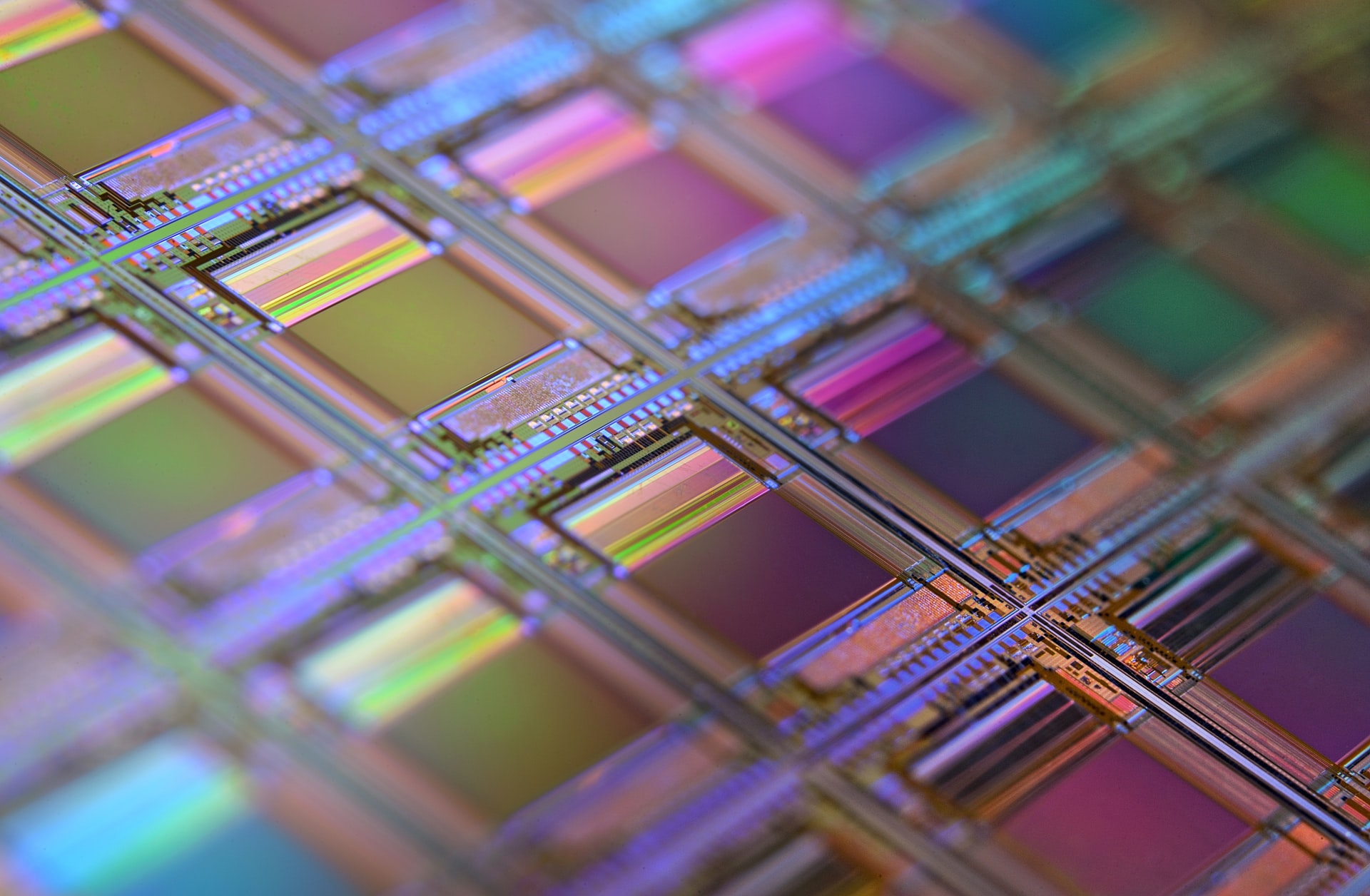

Don’t be fooled by the topic’s technical appearance. This action aims to tip the global balance of power in favour of the United States more than any other presidential policy choice made since the conclusion of the Cold War. Semiconductors are tiny, common, and undervalued.

Every contemporary technology relies on them as its brain. Your phone, TV, and microwave would all be reduced to bricks if semiconductors weren’t used. Both your automobile and aeroplane wouldn’t be able to fly. Semiconductors are essential for the stock market, telecommunications, and weapon systems.

The US Semiconductor Industry Association estimates that in 2021, China held 7% of the global semiconductor industry. Comparatively, Taiwan had 8%, Japan 9%, the EU 9%, Korea 21%, the US 46%, and Korea 21%. The new US limitations are precisely calibrated; they only apply to the most innovative semiconductors, which China is unable to produce on its own.

According to research from the US Centre for Security and Emerging Technology, China “depends on firms with headquarters in the United States and US allies for the cutting-edge computer chips that power cellphones, supercomputers, and artificial intelligence systems,” Furthermore, US technology is “critically dependent” on every modern semiconductor production plant worldwide. This makes the new controls incredibly comprehensive, especially when taken as a whole and considering all of their many facets.

They first prohibited the export of advanced semiconductors to China. Additionally, they impose export restrictions on the equipment, components, and accessories that China would need to build up its own sophisticated semiconductor manufacturing capabilities. The third barrier prevents Americans with specialized skills from working with Chinese organizations, therefore limiting knowledge transfer.

Fourth, all sophisticated chip producers outside the US are covered by extraterritoriality under US rules. All of these firms are allies of the US, and if they don’t abide by the regulations, they won’t be able to use crucial US machinery.

The CHIPS and Science Act, which featured a US$50 billion investment in the domestic semiconductor industry, was enacted by the US in August. This results in what has been called “a new US policy of intentionally strangling huge portions of the Chinese technological industry—strangling with a purpose to kill” when combined with the new regulations. This has a wide range of repercussions.

Limiting China’s ability to “buy and produce certain high-end electronics used in military applications” is the declared goal of the new US limitations. High-end chips, however, are utilised by both the military and the general public. All Chinese research that depends on cutting-edge computers will be restricted as a result of these regulations. This strategy goes beyond merely preserving US technological dominance. Any discipline-specific Chinese study might suffer from it.

The new regulations’ potential immediate impact is unknown. There have been rumours for a while that China has been hoarding chips and equipment, and China will undoubtedly try to circumvent the restrictions. The new US policies will give China’s ongoing attempts to become self-sufficient in semiconductors additional energy, but this is no simple undertaking.

The complexity involved in producing semiconductors is unbelievable. It calls for facilities that would make an operating room seem unclean, as well as very accurate equipment whose calibration is affected by the rotation of the Earth. The manufacturing process becomes more difficult as chip quality increases. Some chip makers contend that without US tools and know-how, China won’t be able to build cutting-edge semiconductors. I’ll leave that discussion to the technical specialists, but it’s important to recognise China’s capacity for innovation.

The US has only received relatively mild criticism from the official spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, who said that it just seeks to “keep its sci-tech monopoly” and “wantonly delay and cripple Chinese enterprises.” The only unambiguous official statement from China thus far is this. A more important matter that requires careful consideration, along with efforts to control supply, is China’s entire response.

The global semiconductor market is already facing a deficit, especially for the less advanced chips made in China. Furthermore, China controls 80% of the world’s supply of rare earth elements, which are necessary for the majority of high-tech components. China may try to stop providing one or both of these, but it would be an unusually symmetrical reaction. It would probably harm China just as much as it would the US.

In a speech to the Communist Party Congress a week after the US limits were announced, President Xi reiterated his country’s objective to “enter the ranks of the world’s most inventive countries, with tremendous self-reliance and strength in research and technology” within five years.

The Biden administration’s regulations severely jeopardise Xi’s plans for China. They want to preserve the US’s technological dominance while undermining China’s capacity for basic research. Given this, a large uptick in China’s response shouldn’t be a surprise.

It is remarkable how many people still choose to tune out when discussing technology and the politics that drive it at a time when the military, economy, and our everyday lives depend on it. If there was ever a moment to pay attention to, it’s right now.

Leaders and analysts from around the world have been speculating for a number of years about the potential of the US to “decouple” from China, or lessen its economic and technical ties to the burgeoning Asian giant. The viability of economic decoupling will be a topic of ongoing discussion. The choice made by Vice President Biden on October 7, 2022, will be remembered as the turning point in the eventual decoupling of US and Chinese technology.

edited and proofread by nikita sharma