On January 2, the first day following winter break, the Supreme Court will rule on appeals against the note ban.

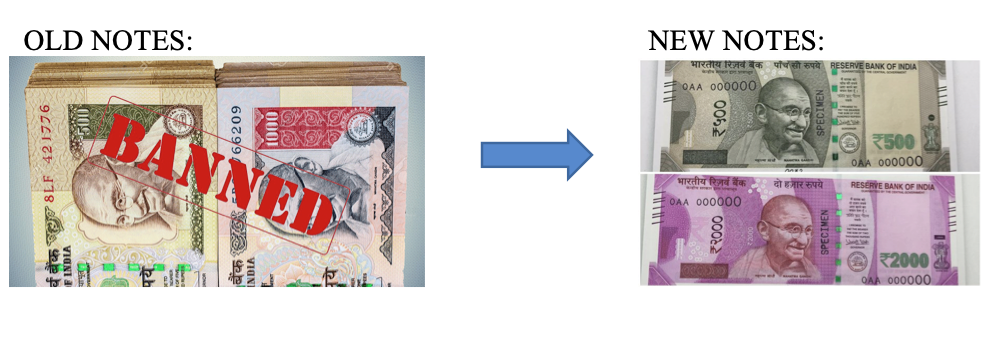

On January 2, the first working day following the holiday season, a five-judge Supreme Court Constitution panel would issue its ruling on several petitions that had contested the Union government’s decision to demonetize the Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 notes on November 8, 2016.

A panel of Justices S Abdul Nazeer, BR Gavai, AS Bopanna, V Ramasubramanian, and BV Nagarathna will rule on all 58 petitions on January 2. The majority of petitions questioned the legality of demonetization, while some called for a new window to swap cash that had been withdrawn but could not be exchanged by the deadline.

According to the agenda for that day, there would be two judgments, one by Justice Gavai and the other by Justice Nagarathna, who would both succeed each other as Chief Justices of India in 2025 and 2027, respectively. It is unknown if the rulings concur or if there was a split decision. The bench had reserved its ruling as of December 7 and was required to issue it before Justice Nazeer’s retirement on January 4.

During proceedings from November 24 to December 7, the bench made overt allusions to the possibility that the government’s decision to demonetize would not be reversed since the clock cannot be turned back after five years. However, it stated that the detailed justifications put forward by the petitioners and the government about various parts of the procedure and sections of the RBI Act could encourage it to establish rules for such activities in the future.

The Center, through Attorney General R. Venkataramani, informed the SC that it opposed opening any new window for the exchange of demonetized Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 currency with new banknotes because doing so would create endless uncertainty and allow illegal funds to enter the country through a backdoor.

The AG had also claimed that the Center opposed the SC adopting future demonetization guidelines, arguing that the SC should defer to the wisdom of policymakers and be slow to conduct an analysis of economic policy. In cases when going back in time, sometimes referred to as “unscrambling the scrambled egg,” cannot effectively provide any actual relief or remedy, Venkataramani has said, “The court would not grant declarations in the abstract or for mere instruction.” It is important to keep in mind that the alleged impacts on people aren’t continuous or continuing; rather, they have already stopped.

Senior attorney P. Chidambaram argued on behalf of the petitioners that the arbitrary removal of the Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 banknotes, which made up more than 86% of the currency notes in use, was seriously faulty and caused tremendous suffering and misery to the populace.

He had contended that the government had requested the RBI to propose demonetization and then reversed the approval procedure. “On November 8th, the RBI board hastily convened without its independent directors and within an hour and a half proposed demonetization. “Then, a waiting cabinet passed it without any debate, and the PM announced the feared choice on television,” he said.

A Supreme Court constitution bench heard over 50 cases challenging the 2016 demonetization program. Six years after the government’s introduction of the policy, a five-judge bench consisting of Justices S. Abdul Nazeer, B.R. Gavai, A.S. Bopanna, V. Ramasubramanian, and B.V. Nagarathna is anticipated to reserve its decision on Wednesday.

Arguments of the Petitioners

Former finance minister and prominent lawyer P Chidambaram criticized the Center’s 2016 demonetization program and argued before the Supreme Court that the government’s method was seriously flawed and should be reversed. Chidambaram said that the decision-making process was terrible and that it violated the RBI Act, making a mockery of the legal system in this nation. He called it the most egregious decision-making process ever. According to P. Chidambaram, the Central Board must suggest demonetization for the government to have any authority to do so; nevertheless, the process was reversed in this instance.

The currency is the RBI’s responsibility, according to Chidambaram, so the process cannot be reversed to have the center advise the RBI. The RBI accepted the center’s guidance and provided its suggestions during a one-hour meeting on the same day. Chidambaram said that the government was suppressing important records related to the decision-making process, such as the central board meeting minutes and the letter from the government to the RBI dated November 7. Chidambaram claims that the Center chose the most drastic action without looking at any other options to deal with false currency or black money and that it also failed to accomplish its goals.

According to Chidambaram, the court can declare that the government’s conduct was unjustified and make it clear that such power cannot be used in any other way, even though it may not be able to reverse what has already been done. He said that it would completely destabilize the nation.

86.4% of the cash in circulation was withdrawn as a result of demonetization.

Chidambaram said that the demonetization initiative resulted in the removal of 86.4% of the cash, and it is safe to assume that the RBI board was not even aware of this information. He argued that by applying the proportionality test, the alleged RBI recommendation and the government’s challenged decision should be overturned because demonetization, as it was carried out, placed an excessive and intolerable burden on people, leading to the loss of hundreds of lives and the livelihood of Indian citizens.

Chidambaram contended that “any” has to imply some but not all under Section 26(2), which allows the center to demonetize “any series” of notes. The provision would become unlawful if “any” was not understood to imply “some” and was instead considered to grant an ultimate power to demonetize any denomination, which would mean all denominations.

People who retained their money in India and didn’t take it outside, according to senior attorney Shyam Divan, found themselves in a completely helpless situation. He said, “The plan doesn’t take into account or consider the condition of those folks.” While making it clear that it is not a criticism of the policy, Divan noted that they are showing how the use of such authority, if allowed unchecked and without court supervision, may have a significant negative influence on people’s lives and means of subsistence.

According to Shyam Divan, the Prime Minister made a significant policy pronouncement that can’t be disregarded. It contained guarantees that people would be allowed to swap demonetized cash.

Arguments by the center:

R Venkataramani, India’s Attorney General, defended the policy, saying it is incorrect to say demonetization failed to achieve its objectives. According to India’s Attorney General R Venkataramani, who supported the program, it is incorrect to claim that demonetization failed to achieve its objectives.

Since fake currency and black money are “such foes that cannot be readily detected and wear masks all the time,” the Attorney General said that demonetization considerably removed fake currency from the system. According to the AG, it is a well-established notion that judicial deterrents are necessary for questions of economic policy. He asserted that the court cannot be asked to decide whether inactivity or perfection in the area of economic policy and law is acceptable.

As electronic transactions rose, the value of UPI transactions increased, and digitalization together with demonetization made electronic payment systems practical and cost-effective, the AG argued that the demonetization policy had positives for the digital economy. The AG further stated that the impact on people that have been highlighted has ended. There is no ongoing harm that justifies the court’s involvement. “The proportionality test won’t be relevant.” “Larger economic gains on the one hand and people’s occasional misery on the other are incomparable,” AG said.

The AG stated that when there is a greater public interest engaged in advancing toward a wide spectrum of economic and policy reform, difficulties experienced by individuals cannot be the only relevant element to be taken into consideration.

The AG stated that setting the cut-off date wasn’t random and that they weren’t blind to the hardships brought to the public, but that it would be impossible to evaluate all potential outcomes in a situation of this nature. The essential integrity of the decision-making process would be compromised if it were eliminated.

Reserve Bank of India’s Arguments

In contrast to what the petitioners have claimed, senior advocate Jaideep Gupta said on behalf of the RBI that the procedure required by the RBI Act to make a recommendation to the Center was followed and the required quorum was met. Gupta disagreed with Chidambaram’s claims that the rules requiring a quorum had not been observed and that the government and the RBI had withheld information about the meeting and the quorum.

Gupta informed the SC that the Central Board of the RBI had the necessary quorum when it decided to propose the demonetization of the 500 and 1000 rupee notes in 2016. The bench demanded to know how many members were present. Gupta claimed that Chidambaram was “fishing,” and that by saying that the quorum wasn’t fulfilled, he was responsible for demonstrating that point. Gupta claims that the RBI proposed the idea, and the process was followed. Gupta rejected the petitioners’ assertion that the RBI must begin the demonetization process in accordance with Section 26(2) of the RBI Act.

According to him, the clause does not mention initiation, with the RBI’s proposal serving as the intermediary step and the Center’s decision as the decisive one. In response to criticisms that the judgment was made in just two days, Gupta claimed that the Central Board didn’t have to start from zero because it already had some material at its disposal. Gupta stated unequivocally that time or pace alone does not indicate a problem.” Demonetization cannot be successful without confidentiality and rapidity,” he insisted. Gupta said that possibilities had been provided for individuals and that several agreements had been made to let them trade money.

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

The Constitution bench made several oral observations and asked both of the attorneys for the petitioners, the Center, and the RBI significant questions. The bench had inquired as to how many people were present at the Central Board meeting of the RBI when the decision was made to propose the demonetization of the 500 and 1000 rupee notes in 2016. Orally, Justice Gavai requested information about the quorum from the Reserve Bank of India. “How many participants were there?” “It should not be difficult to inform us,” he remarked.

A day later, Senior Attorney Jaideep Gupta notified the court that an affidavit had been submitted, demonstrating that the quorum requirements were satisfied. While quorum is defined as four directors, more than four were present, he said. The bench observed that while it may not get into the merits of the judgment, the method can be reviewed. This was in response to an argument made on behalf of the RBI that the court would not review an economic policy move judicially.

“The court will not discuss the merits of a decision, but it may discuss how the conclusion was reached.” “Due to its economic nature, the court cannot just sit back and do nothing,” BV Nagarathna, a judge, remarked. Regarding arguments regarding whether or not there can be a judicial review of the central government’s decision to implement demonetization, the bench stated that even the petitioners had agreed that, even under earlier rulings from the SC, the court could not examine the correctness of the decision but only the correctness of the decision-making process when exercising its judicial review power.

Justice Gavai stated that the most we can look at is whether or not there was legal conformity. The bench noted that under the Specified Notes Act of 2017, RBI has the authority to permit such exchanges if it is satisfied that the claims are legitimate while taking into account the problem of individual complaints from those who missed the deadline for swapping the demonetized currency notes. Furthermore, it would be an arbitrary use of authority to deny claims in legitimate instances.

Edited by Prakriti Arora