Majority of India’s 900 million Workforce have Stop Looking for Jobs: Report.

Majority of India’s 900 million Workforce have Stop Looking for Jobs: Report.

India’s job creation problem is growing into a more significant threat: many people are no longer looking for work. Frustrated at not finding the right kind of jobs, millions of Indians, specifically women, are exiting the labour force altogether, according to new data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt, a private research firm in Mumbai.

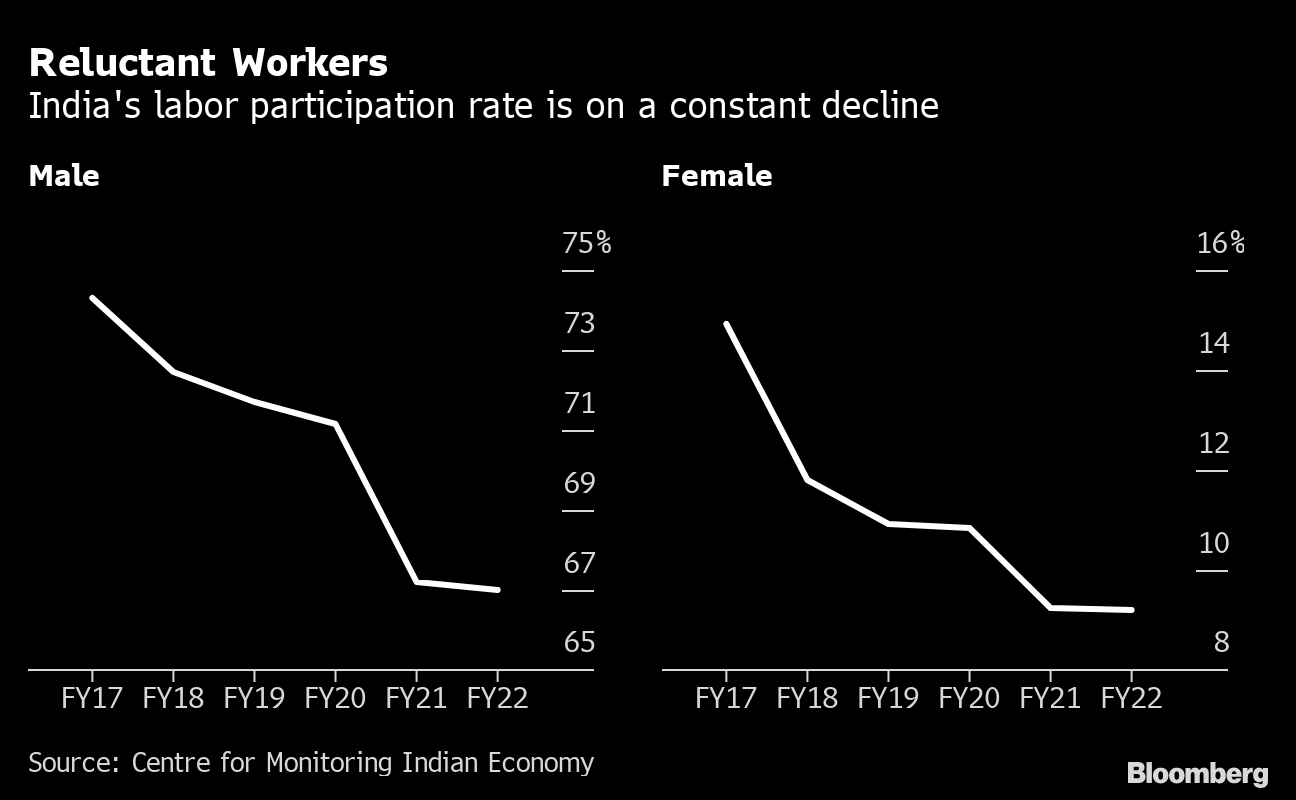

With India, which is betting on all the young workers to drive growth in one of the world’s fastest-expanding economies and growth, the latest numbers are an ominous harbinger. Between the years 2017 and 2022, the overall labour participation rate has dropped from 46 per cent to 40 per cent. In the women, the data is even starker. About 21 million have disappeared from the workforce, leaving only 9% of the deserved population employed or looking for stable places.

)

More of the 900 million Indians are of legal working age, roughly the population of the US and Russia combined. They don’t want a job, according to the CMIE.

“The large share of the discouraged workers have suggested that India is unlikely to reap the dividend that its young population has to provide,” said Kunal Kundu, an economist with Societe Generale GSC Pvt in Bengaluru. “India will be remaining in a middle-income trap, with the K-shaped growth path further fueling inequality.”

India’s challenges around job creation are well-documented. With about two-thirds of the population between 15 and 64, competition for anything beyond menial labour is fierce. Stable positions in the government routinely have drawn millions of applications, and entrance to top engineering schools is practically a crapshoot.

According to a youth bulge, India needs to create at least 90 million new non-farm jobs by 2030 to keep pace with a 2020 report by McKinsey Global Institute. That requires a yearly GDP growth of 8% to 8.5%.

“I’m dependent on everyone for every penny,” stated Shivani Thakur, who is 25, who later left a hotel job due to the hours that were so irregular. Failing to put the young people to work better could push the country off the road to developed-country status.

Though the country has made great strides in liberalizing its economy, drawing in Amazon.com Inc and Apple Inc, India’s dependency ratio has started rising soon. Most economists worry that the country may miss the window to reap a demographic dividend. In simple words, Indians may become older but not more prosperous.

A decline in labour predates the pandemic. In 2016, after the government banned all currency notes to stamp out black money, the economy sputtered. The roll-out of a nationwide sales tax simultaneously posed another challenge. The country has struggled to adapt to the transition from an informal to a formal kind of economy.

Explanations for the drop in the percentage of workforce participation vary. The Unemployed Indians are often students or homemakers, and many of them survive on rental income, the pensions of all the elderly household members or government transfers. In a world of quick technological changes, others fall behind in having marketable skill-sets.

For all the women, the reasons sometimes relate to safety or time-consuming responsibilities at the house. Though they present 49% of India’s population, women have contributed only 18 per cent of their economic output, about half of the global average.

“Women don’t join the labour force in many numbers because jobs are often not kind to them,” asserted Mahesh Vyas of CMIE. “For example, men are willing to change the trains to reach their success or job, and women are less likely to be willing to do that kind of thing. This is happening on an immense scale.”

The government of India has tried every possible way to address the problem, including announcing plans to raise the minimum marriage age for women to 21 years. The recent report received from the State Bank of India could improve workforce participation by freeing women to pursue higher education and a career.

Changing cultural expectations is perhaps the more challenging part.

After graduating from his college, Thakur started working as a mehndi artist, earning a monthly salary of about 20,000 rupees ($260) applying henna on guests’ hands at a 5-star hotel in Agra.

But because of late and long working hours, her parents asked her to quit the job this year. They are now deciding to marry her off. A life of financial independence, she said, was slipping away.

“The future is being destroyed in front of my eyes,” Thakur claimed. “I have tried everything to convince her parents, but nothing is working.”

India’s challenges around job creation are well-documented. With about two-thirds of the inhabitants between 15 and 64, competitors for something past menial labour are fierce. There are Stable positions in the authorities routinely draw thousands and thousands of purposes, and entrance to high engineering colleges is virtually a crapshoot.

Although Prime Minister Narendra Modi has prioritized jobs, urgent India to attempt for “Amrit Kaal,” or a golden period of development, his administration has made restricted progress in fixing inconceivable demographic math. To preserve the tempo with a youth bulge, India must create a minimum of 90 million new non-farm jobs by 2030, following a 2020 report by McKinsey Global Institute. Again, that would require an annual GDP development of 8% to eight.5%.

A decline in labour predates the pandemic. In 2016, after the federal government banned the forex notes to stamp out black cash, the economic system sputtered. The roll-out of a country’s gross sales tax across a similar time posed one other problem. India has struggled to adapt to the change from an off-the-cuff to a formal economic system.

Explanations for the drop in workforce participation fluctuate. Unemployed Indians are sometimes college homemakers or college students, and many of them have survived on rental revenue, the pensions of aged family members or authorities transfers. In a world where technology is changing, others are merely falling behind in having marketable skill-sets.

For girls, the explanations generally relate to security or time-consuming tasks at the house. Though they signify 49% of India’s inhabitants, girls contribute solely 18% of its financial output, about half the worldwide common.

The authorities have tried to deal with the issue and say they plan to boost girls’ minimum marriage age to 21. That may enhance workforce participation by liberating girls to pursue more excellent training and a profession, following the latest report from the State Bank of India.

Changing cultural expectations is maybe the more durable half.

After graduating from faculty, Thakur began working as a mehndi artist, income a month-to-month wage of about 20,000 rupees ($260), using henna on the palms of the company at a five-star resort within the metropolis of Agra.

But as a result of late working hours, her dad and mom requested her to stop this for 12 months. They, at the moment, are planning to marry her off. A life of monetary independence, she mentioned, is slipping away.