Is India following Sri Lanka on the road to Economic Crisis?

Is India following Sri Lanka on the road to Economic Crisis?

The economic crisis in Sri Lanka keeps growing worse. What initially manifested as an economic crisis instead manifested as social unrest, which has since transformed into a political revolution. The country’s 22 million people are struggling due to sharp price rises for essentials, including food, electricity, and medicine.

Sri Lanka’s lack of foreign reserves, which its government and people require to pay for imports, is the immediate source of the problem. It needs further explanation as to how it ended up in this circumstance. It’s a case of squandering money, unwise currency management, and continued poor leadership. Many experts attribute the bad economic mismanagement to President Rajapaksa.

The current economic crisis in Sri Lanka has been the worst in recent times. Daily power outages and shortages of essentials like fuel, food, and medicines have been a struggle for the masses. The rate of inflation has surpassed 50%. In April, protests began in the country’s capital, Colombo, and fast expanded. Following months of widespread protests over the island’s economic hardships, the president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, fled the country, and a state of emergency was subsequently declared.

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis has been sparked by a decline in the country’s primary source of revenue from tourism as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic disruption brought on by lockdowns to contain the virus. However, the political rulers of the country are to blame for pushing the nation to the brink of collapse with debt-ridden infrastructure-led growth and mindless tax cuts.

The Sri Lankan government entirely disregarded industries like food production and concentrated all of their efforts on industries like tourism that brought in foreign currency. However, the COVID-19 pandemic brought about the collapse of the tourism industry, plunging the nation into a dire situation.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the president, is the most recent target of public resentment. Gotabaya announced his resignation as tens of thousands of protesters surrounded his home. The majority of the Rajapaksa family members are currently in opposition. Former Sri Lankan Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa was also blamed for the current economic crisis by his people after orchestrating the ruthless extermination of Tamils with the support of several nations and winning the support of the majority Sinhalese.

Now, the nation’s future is in jeopardy. Nobody knows where Sri Lanka is going with surging inflation and rising food costs, negative investor sentiment, declining foreign exchange reserves, and a catastrophic agricultural crisis. The ongoing turmoil in Sri Lanka is thought to be the result of decades of majoritarianism and hyper-nationalism, which allegedly peaked under Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s rule.

Sri Lanka’s President Rajapaksas’s Bad Economic Policies and Samaraweera’s Prediction of Doom.

At a time when stagflation (low growth-high inflation-low production-higher unemployment) is still hurting investors in other developing countries, specifically that outside of South Asia, Sri Lanka’s default on a $12.6 billion debt of outstanding foreign bonds has become a flashing warning sign.

Sri Lanka’s descent into chaos needs to be seen as the result of repeatedly pursuing bad economics in a climate of populist politics, where decisions were taken without thinking about consequences, similar to what is currently being seen in India. For instance, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the presidential contender from Sri Lanka, suggested tax cuts so recklessly ahead of the election in November 2019 that the ruling party assumed it was a marketing ploy.

At the time, Sri Lanka’s Finance Minister, Magala Samaraweera, described the campaign move as a ‘dangerous pledge,’ saying that cutting the VAT from 15 to 8 per cent would be disastrous for an economy that already had a weak tax base, a high level of debt in foreign currency, and a significant reliance on tourism revenue to pay for a high import bill.

Samaraweera issued a warning that the entire nation would fall bankrupt if these recommendations were carried out in this manner. However, after taking office, the Rajapaksas proceeded to enact populist tax cuts, and it took less than 30 months for Samaraweera’s prophecy of an impending economic Armageddon to materialise.

A string of flawed choices of Sri Lanka’s Government.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Sri Lanka’s growth was lagging. In a recent report, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) described how the Sri Lankan economy was badly impacted by COVID-19. In 2020, the annual GDP growth rate, which was 2.3% in 2019, dropped to -3.6%.

The Sri Lankan government swiftly announced several relief measures during the pandemic, including a macroeconomic policy change, an increase in expenditure on the social safety net, and loan repayment moratoria for impacted enterprises.

In addition to these efforts, a vigorous vaccination campaign assisted in restoring GDP growth to a recovered rate of 3.6 per cent in 2021, with mobility indicators effectively returning to their pre-pandemic levels and tourist arrivals beginning to recover in late 2021.

However, the pandemic, which forced multiple harsh lockdowns, resulted in a massive loss of tourism earnings, one of the main sources of income for the country. This was the major cause of the downward spiral of Sri Lanka’s economy. Some other reasons for the economic crisis in Sri Lanka are;

- It was challenging to recover from the pandemic because of the pre-pandemic policy climate, which made the economy’s problems worse. The Rajapaksa administration’s populist tax cuts have constrained the government’s options for raising income. The amount of money sent home by Sri Lankan expatriates was already declining.

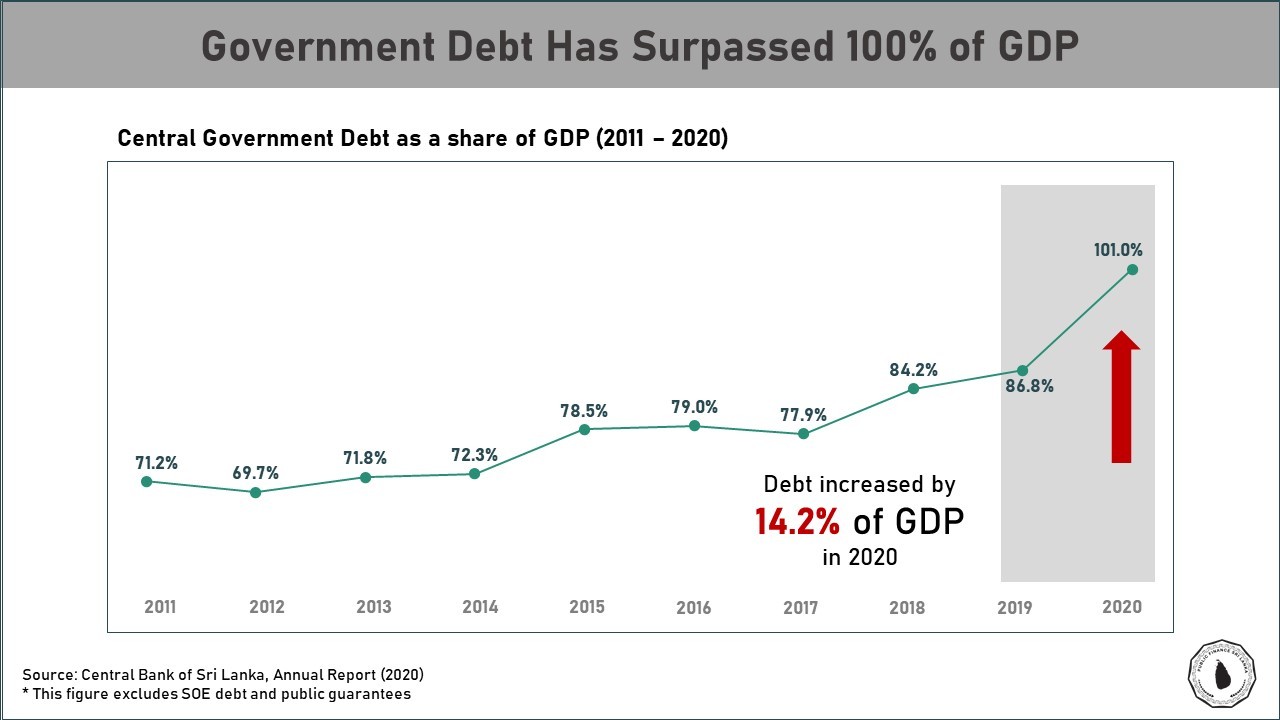

- The negative effects of COVID-19 and the announced relief spending measures resulted in increased government spending (with a low revenue base); fiscal deficits exceeded 10% of GDP in 2020 and 2021, and the economy saw a sharp rise in public debt to 119.0% of GDP in 2021.

- The low-growth, foreign capital-dependent Sri Lankan economy thus lost access to global capital markets in 2020, which led to a drop in global reserves to dangerously low levels and a significant increase in the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s (CBSL) direct loans to the government.

- Foreign exchange (FX) shortages resulted from the repayment of external debt and a growing current account deficit, although the official exchange rate remained de facto-fixed from April 2021.

- Sri Lanka decided to concentrate on supplying goods to its internal market rather than attempting to increase foreign trade after its civil war ended in 2009. This meant that while the cost of imports kept rising, its income from exports to foreign nations remained low. As a result, Sri Lanka’s foreign currency reserves are depleted due to its imports of $3 billion (£2.3 billion) more than exports.

- Rajapaksa’s switch to organic farming last year, which included a ban on chemical fertilisers and farmer protests, made things worse by causing a decrease in the output of crucial tea and rice crops. Despite a high import expense for fuel, imports kept rising, severely depleting the foreign exchange reserves.

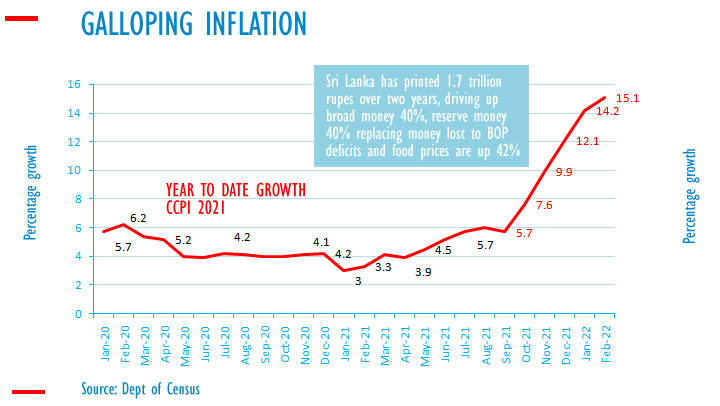

- Inflation rates increased over the six months, reaching double digits in December 2021. At the same time, they were reflecting the cascading effects of imported inflation brought on by rising oil and food import prices, supply shocks, and an increase in domestic consumer demand, all in the context of loose monetary policy.

- The unemployment rate also kept rising, which infuriated people and finally led to them taking to the streets to protest the government’s poorly thought-out economic policy decisions.

Sri Lanka needs to make significant changes in its Macroeconomic Policies to save its Economy.

The Sri Lankan economy will require a strong path toward a medium- to long-term, revenue-based budget consolidation approach going forward from a macroeconomic perspective. The VAT, income, and company (direct) taxes must all be strengthened through incremental rate increases and base-widening measures as part of economic and political reforms.

To lessen the risks from loss-making public companies, the fiscal adjustment would also need to be complemented by modifications to the energy price structure. To make sure that the recent breach of the inflation goal band is only transient, near-term monetary policy tightening is required. Restructuring the fiscal rule is one example of an institution-building reform that would assist in ensuring the strategy’s legitimacy.

Other (longer-term) changes would need to be made, such as establishing a flexible exchange rate policy and a medium- to long-term debt reduction plan, all the while making sure that the majority of government spending in specific social areas, like healthcare, education, and social security goals, continues.

Is India following Sri Lanka on the road to Economic Crisis?

An unparalleled economic and political crisis is currently afflicting Sri Lanka. The southern neighbour’s economic crisis has been building for a while, and recent geopolitical events have pushed the country toward economic instability and bankruptcy. The Sri Lankan government brought this problem upon themselves by making careless borrowings that even exceeded the country’s GDP. Concessionary borrowings were replaced with commercial borrowings, which have higher interest rates and shorter maturity terms, as the debt’s composition transformed over time.

After 2016, much changed for Sri Lanka, just like it did for India after 2014. Rajapaksa’s politics, the strategy of running the country, and flagrant contempt for democratic norms are strikingly similar to how Narendra Modi has governed India since 2014. It is important to understand that Sri Lanka’s spiral into instability is the result of continuously pursuing bad economics in an atmosphere of populist politics, where decisions were made without weighing the consequences, similar to what is happening right now in India.

The unsettling state of affairs being observed in India’s own (macro) politico-economic scenario bears a disturbing resemblance to centralised ad hoc policy measures and tax cuts for populist reasons (before the pandemic). The inability to collect estimated revenue for the government’s spending needs, seeing a rise in government debt, provides limited autonomy to the central bank for targeting inflation while banning chemical fertilisers.

More than half of the Union’s total budget is made up of debt, and few investments are being made in profitable industries. More than Rs 17 lakh crore, or 45% of the budget size, was generated by borrowing out of the government’s overall budget of more than Rs 39 lakh crore. Additionally, the Centre is in the process of selling off some of its assets, like LIC, to raise Rs 75,000 crore.

This is a sign that the Center is approaching a damaging condition. We need to analyse the Sri Lankan crisis in this context. Over half of the budget of the Indian government is borrowed. The tax is not being properly collected. The centre is not increasing its investments in the industries that are productive. Additionally, the prices of fuel and kerosene have seen a considerable increase over the years, and if these keep on rising, India will soon face a food and fuel crisis like that of Sri Lanka.

The Sri Lankan government slavishly clung to the globalisation policy, focusing only on industries that generated foreign income, like tourism, while disregarding the basic industries, like agriculture, which caused the country’s economy to drastically decline during the COVID-19 pandemic. India, which is also following a similar approach, should learn from Sri Lanka’s aggressive globalisation strategy that led to its economic crisis.

If the BJP-led Union government continues to promote ‘nefarious anti-people policies’ like ‘one nation, one language, one religion, one law, and one election,’ pluralistic India will soon witness what is currently transpiring in Sri Lanka (public unrest and economic crisis), according to Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi chief Thol. Thirumavalavan. He predicted that as long as the Modi-led government was in charge at the Center, the cost of fuel and other essentials would rise. He claimed that the Central government primarily cared about the well-being and financial success of big businesses, oppressing the poor.

A populist government that follows majoritarian politics to increase its “power,” destroys public institutions, and implements ad hoc economic policy measures is doomed to fall into an unstoppable economic cycle that negatively affects its citizens. This cycle begins with a cycle of low growth, low production, and low employment and is then exacerbated by the negative effects of sustained inflation. All of these will result in a severe economic crisis.

Mr Rajapaksa, who earlier used divisive tactics in the name of religion, race, and language, is now on the run to protect himself from the Sinhalese. The Narendra Modi-led government in India is also pursuing an identical approach to encourage the pluralistic country to adopt ‘one culture, one language, one religion, one party’ policies to ensure the BJP’s perpetual rule. If so, the rulers and their followers should realise that what is occurring in Sri Lanka will probably occur in India soon.

Democratic groups opposing this government, including the Left, should unite under one banner if the country is to be preserved from this chaotic regime. Keeping the geopolitical and geostrategic repercussions of Sri Lanka’s economic and political crises under appropriate control should be India’s top concern at home.

However, the island’s saga may work as an indicator for emerging markets, especially those in South Asia, where populist policies, excessive reliance on capital borrowed from abroad, and an environment where economic policy is made independently may result in shortages that are then made worse by inflation. This will potentially disrupt national economies since it is an “invisible tax” on the less-fortunate segments of society.

Sri Lanka is a cautionary narrative for governments against adopting ideologically-driven policies that cause social unrest, exacerbate inequality, erode industrial and agricultural competitiveness, and create fiscal vulnerability, even though a combination of exceptionally unfavourable factors was required to bring Sri Lanka to its recent state.

Edited by Prakriti Arora