India’s job crisis won’t be solved by reservation

Why would reservation not address India’s employment crisis?

To garner votes, our netas are increasingly using quota politics. Regarding India’s job issue, education reform, not a reservation, is the way to go.

Extreme poverty, defined by the World Bank as consumption below $1.90 per day per person, has nearly vanished in India, according to research by Surjit Bhalla, Arvind Virmani, and Karan Bhasin. India’s poverty line is almost comparable to that of the World Bank. The new analysis uses a technique developed by the World Bank. According to the report, the poverty rate has dropped dramatically from 31.9 per cent in 2004 to 5.1 per cent in 2014 and 0.86 per cent in 2020.

This technique, which ignores data from the 2017-18 NSSO survey, will be slammed by critics. On the other hand, other studies demonstrate that poverty has been steadily declining in recent decades.

These poverty studies will not be discussed in this column. Doesn’t this weaken the government’s legal argument for the 2019 law giving a 10% EWS quota if poverty is reducing fast without employment or educational quotas for economically weaker sections (EWS)? In 1992, when a large portion of the population was living in poverty, the highest court ruled that an EWS quota was unjustified. Is such a quota justified now, when poverty is estimated to be much lower?

Discrimination based on caste, religion, gender, or place of birth is prohibited under the constitution. It does, however, enable job and educational quotas as a kind of reverse discrimination for Dalits and tribals who have been subjected to long-term prejudice and now require a time of reverse discrimination. Reservations for economically and socially disadvantaged people are also allowed under the constitution. By linking OBCs (other backward castes) with the legally recognised “backward classes,” politically strong organisations, particularly caste-based parties, have requested and received quotas.

The 10% EWS quota was approved by all parties. Quotas are clearly seen by politicians as a means of gaining votes rather than correcting prejudice.

In 1991, the government established a 27 per cent quota for OBCs and a ten per cent quota for EWS. The EWS quota was overturned by the Supreme Court since it was unrelated to historical infirmity, while the OBC quota was upheld. With a 15% quota for Dalits and a 7.5 per cent quota for tribals, a total of 49.5 per cent of all jobs were now reserved. The court stated that anything more would be incompatible with the principle of non-discrimination.

However, India’s employment need is severe, leading to politically complex requests for more. The majority of formal sector employment is provided by the federal and provincial governments. Government positions are coveted because they offer complete employment security. Last January, protests erupted in Bihar for three days over alleged inequity in exams for 35,000 Railway positions, for which 10 million people applied. In 2016, 17,000 applicants applied for 114 sweeper positions in Amroha, including those with MBA and BTech degrees.

The employment shortage stems from a failing educational system that generates unemployed high school and college graduates with no practical skills. That is a heinous act. However, quotas, which only postpone educational changes, will not fix the problem. All parties approved the 10% quota for EWS, and the BJP bragged that the new quota allowed Muslims and Christians to share quotas for the first time. Quotas are clearly seen by politicians as a means of gaining votes rather than correcting prejudice.

Poverty among the higher castes is unrelated to historical prejudice. They have a history of becoming oppressors rather than victims.

EWS are people with a household income of less than Rs. 8 lakh per year, farmland of fewer than five acres, and urban property of fewer than 1,000 sq ft, according to the government. According to the 2011-12 NSSO study, the wealthiest 5% of Indians spent just $4,481 per capita in rural regions and $10,281 in urban areas. It’s possible that per capita income was 20% higher.

Only 8.25 per cent of rural households earned more than $10,000 per month, according to the 2011 Socio-Economic Caste Census. Despite the fact that incomes have grown since then, more than 80% of Indians are expected to be eligible for EWS quotas. That is a farce that has nothing to do with past discrimination.

According to the 2015-16 Agriculture Census, 86 per cent of land holdings were less than five acres. EWS is available to everyone. This is absurd once more. Clearly, the EWS quota is intended to encompass as many people as possible, not only the poorest, in order to garner the most votes. This is crass politics at its finest, and it is a compelling cause for the Supreme Court to overturn the quota.

As a kind of reverse discrimination, quotas were assigned to Dalits, Tribals, and OBCs. Poverty among the upper castes, on the other hand, is not the result of historical prejudice. They have a history of becoming oppressors rather than victims. Some people may have fallen into poverty as a result of gambling or drug addiction, the death of a breadwinner, medical issues, or natural calamities. Such families are deserving of assistance. However, such assistance does not entail quotas anywhere around the globe.

Minimum marks are required to gain a place at JNU or the IAS, even with quotas. The poorest people are illiterate and would never achieve even the lowest grades. The creamy layer — higher-caste individuals who have been momentarily impoverished due to financial shocks but are otherwise part of the top social structure — would be the biggest winners. Some will be wealthy criminals hidden in plain sight.

They should not be helped by the Supreme Court. Instead, it should warn the government that the solution to the job problem is educational reform, not quotas.

Because we have less employment and a larger population, reservations will not be able to fix the job situation in India. The framers of the Indian constitution thought that reservation had a distinct meaning. Reservation was justified as a means of empowering society’s weakest members. As a result, SC/ST reservations were only scheduled for ten years and were to be revisited. Instead of a review, we went with OBC reservations, which were further divided according to EWS.

Reservation is a voting-banking tool. Social justice and empowerment of the lower sections have given way to vote bank politics, and no political party is willing to abandon reservation. When individuals come on the streets as vegetable sellers or chai pakode wale, it is incorrect to call poverty falling. This does not provide them with a consistent source of income, which is necessary to alleviate poverty. However, the initial intention of reservation, which was to promote social upliftment, was realised when an SC/ST IAS officer, Dabi, may remarry after divorce and receive a limelight.

Using the quota system, her sister has also become an IAS. The problem with the reservation system is that those who have benefited and updated their financial and social status continue to enjoy the benefits, while others who require these benefits are denied. Actually, caste reservations should be removed, and those who are deserving, regardless of social origin, should be provided with opportunities to advance.

This Rs 8 lakh ceiling, or less than five acres of land spending capacity in rural or urban areas, is discrimination, which the Indian constitution forbids and ensures that all citizens have equal rights. In this process, Muslim personal law should give way to a country-wide civil code.

Caste-based reservation and the lack of adoption of a standard civil code are the two main sins still practised in the country. It is unique in this nation that a Hindu converts to Islam in order to marry for the second time and have a second wife.

To fix India’s job issue, we need to create jobs. We don’t have enough private entrepreneurs who can hire people, nor do we have a government that is interested in selling government assets and industries to corporations, further diminishing jobs in the nation. Making in India is a positive thing, but the government is encouraging business entities to import under licence, limiting job opportunities in the nation. Reservations must be removed in order to provide equal opportunity to all citizens of the country.

In India 2022, there are 5 significant reasons for educated unemployment

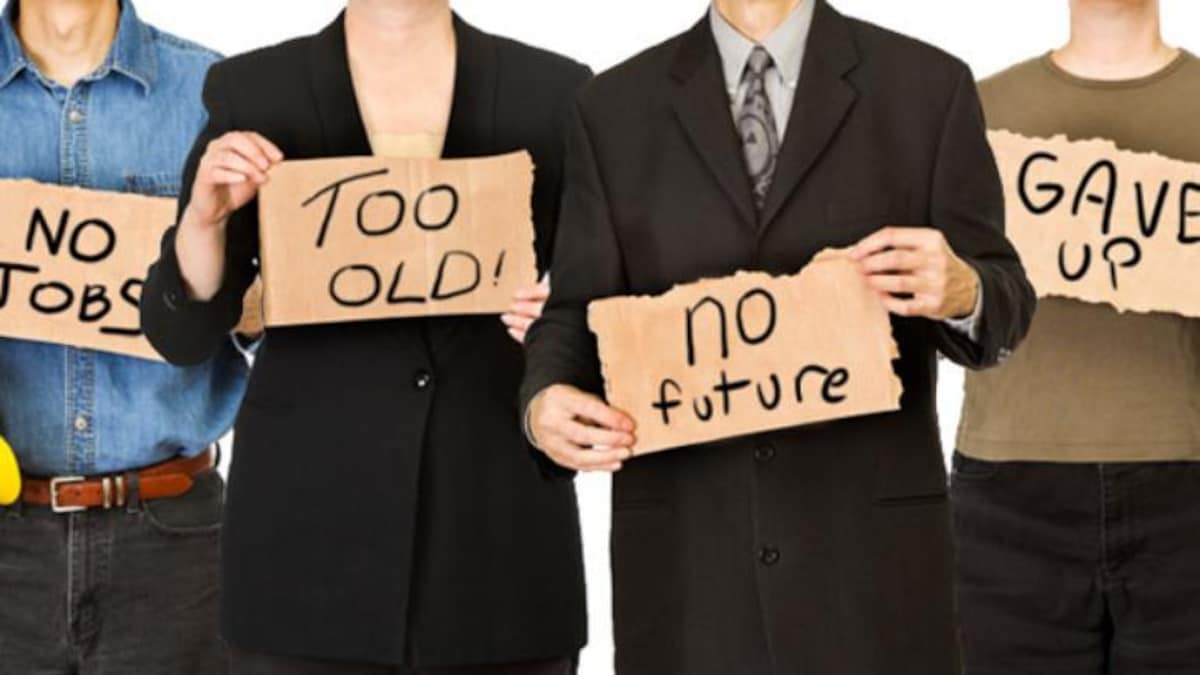

In its most basic form, educated unemployment happens when a person with a relevant degree and a desire to work at industry standard wages/salaries is unable to find work in a particular industry.

Youth unemployment is a major concern in India and one of the most often mentioned issues, yet it has yet to be addressed. Education for us Indians comprises of graduating from high school and college. However, we are unaware that this is not the case.

The amount of years you spent in high school or college has no bearing on whether or not you will be employed. What important is the quality of education and information gained throughout these years?

Most of our childhood and youth is spent memorising textbooks, with very little time spent on actual knowledge and skill acquisition.

According to research, in India, about 2 million graduates and half a million post-graduates are unemployed. In India, around 47% of graduates are unsuitable for any industry position. Above all, in India, the rate of educated unemployment rises as one advance in education. While youth unemployment is approximately 3.6 per cent at the primary level, it is over 8% at the graduate level and 9.3 per cent at the post-graduate level.

Consider the following five primary causes of educated unemployment in India:

1. Population

Overpopulation, or population growth, has always been a stumbling barrier to various difficulties. This includes everything from healthcare to the basic shelter to young unemployment in India. With a population of 1.38 billion people, we can scarcely expect an economy to meet the needs of every individual. The number is too large to satisfy basic food and medical conditions, let alone find employment and places.

Regarding India’s youth population and unemployment, a source claims that the country experiences an annual growth of 8-9 per cent in higher education enrolment. India is one of the top five countries with the most prominent university students. The issue is that there is no corresponding increase in the number of opportunities.

Graduates are in more excellent supply than there is a need. This divide grows even more during recessions, when businesses and organisations struggle to cope with the deteriorating economy, resulting in layoffs and a lack of new hires.

2. Low Institution/University Standards

When we compare our educational institutions to those outside of the country, we can see that our teaching methods are fundamentally flawed. To name a few examples, youth unemployment is caused by an outdated curriculum, insufficient teaching resources, and a lack of essential infrastructure. Students are not educated to meet the needs of the economy or to completely learn a topic; rather, they are instructed to cram the material and get excellent grades.

In 1990, there were 337 engineering colleges in India; by 2017, there were 6427.

Above all, the existing educational system has become a business for the majority of individuals. Education costs have grown considerably, yet the quality of education has not improved. As a result, the majority of young people are forced to attend government institutions, which are far inferior to private colleges in terms of quality. While population growth necessitates an increase in the number of institutions in every given field, the quality of these institutions was never addressed. Due to a lack of financial resources and assistance, India’s expanding number of institutions simply means a drop in educational rates.

3. Lack of right skills

In India, a lack of skills is among the main causes of young unemployment. A critical component of being suitable for work in any field is equipping oneself with essential skills and focusing on competency. However, most of today’s children lack the abilities that a job description demands.

The majority of graduates do not possess the necessary communication skills in English. Primary schools play a crucial role in developing critical skills. At the primary level, fundamental abilities such as communication and language must be emphasized.

4. Job opportunity & qualification mismatch

In India, low pay has been on the verge of putting educated people out of work. Even India’s premier schools and institutes have struggled to find employment that pays well.

Research shows that 48% of urban teenagers find it difficult to secure a job. Three-quarters of employed individuals do not like their jobs, and this also implies a lack of favourable working conditions.

In recent years, the media have documented a lack of adequate pay in engineering and law. In spite of their success, corporates and lawyers do not fairly reward their employees and juniors. For many graduates, this is a barrier to employment, and they ignore reasonable employment opportunities that present themselves, leaving themselves jobless.

5. Meeting Societal responsibilities

Women have always been at the forefront of the conversation when it comes to employment and unemployment in India. After graduation, most women abandon their plans to take on a job with responsibilities, primarily due to the possibility of marriage.

In India, the concept of a working woman is still not universally recognised.

While most women want to advance in their jobs, time restrictions and family obligations have historically kept them from taking advantage of good possibilities. There is an obvious need to focus on eradicating female youth unemployment in India through increasing female empowerment knowledge.

Conclusion

India’s government and academia have long debated the issue of employment and unemployment. Employees face many challenges, including unfair working conditions, exploitation, and inadequate compensation, to name a few.

In India, we have laws addressing employment and unemployment, but they have not been implemented. Among the measures to limit educated unemployment in India are regulating salaries, organizing the private sector, and establishing fees for colleges.

The quality of education should be the government’s and people’s top priority. A more serious approach to the skill development programme of the ruling government is long overdue.

edited and proofread by nikita sharma