How is legal system is India is used as a weapon to harass, silent and threatn people

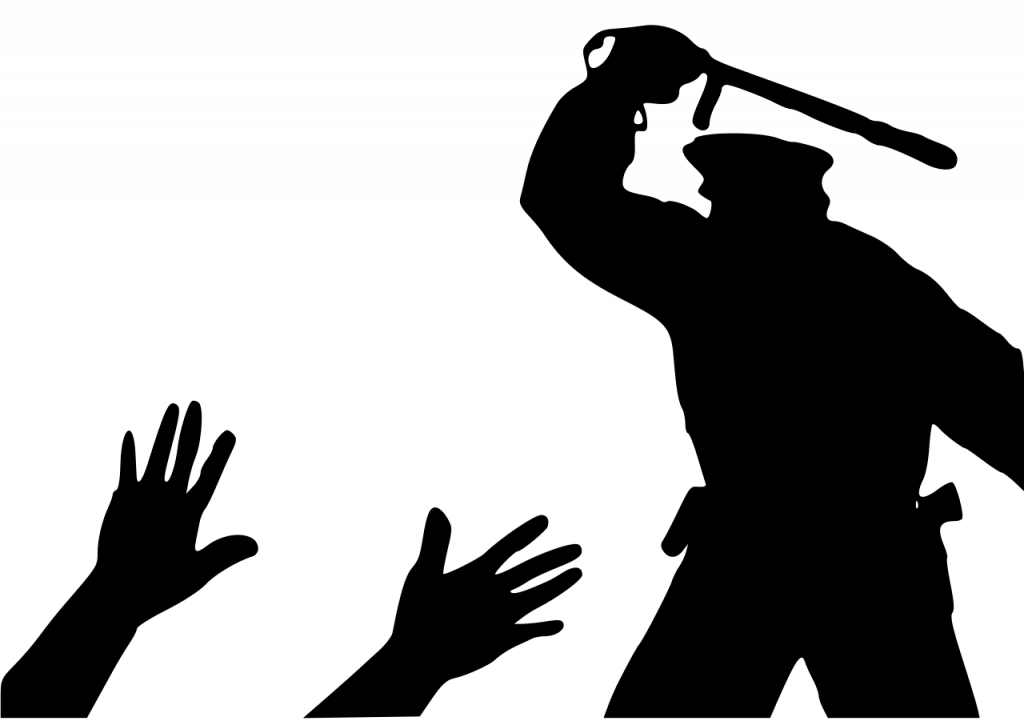

How is legal system is India is used as a weapon to harass, silent and threatn people Democracies all around the world have been put to the test during the last few years. Discussions over free speech, blasphemy, sedition, hate speech, and bans are becoming commonplace both inside and outside of India. The phrase “sedition” has been popular again, particularly after 2016, as seen by TV hosts yelling about it, “WhatsApp University,” social media, newspapers, and, of course, the talks we have in our living rooms over what constitutes “anti-national” speech.

While it was all going viral in 2016, I was a complete novice with little knowledge of politics and political science, so the word “sedition” itself initially seemed rather offensive. I may not have been able to capture the complete discussion on sedition in one post, but I did try to provide my viewpoint.

To me, the sedition legislation accurately captures the dynamic between an oppressive, dictatorial regime and its people. This colonial-era criminal statute was intended to punish people in British India for “disaffection” with the legal authority. It’s interesting to note that the first case of sedition under Section 124A was brought against the Bangabasi, a Calcutta weekly, in the year 1891. The second instance was Bal Gangadhar Tilak and his publication of the poem “Shivaji’s Utterances” in the monthly Kesari.

Tilak was judged guilty by the British administration of seeking to stir up discontent and treachery by portraying Shivaji as a warrior who revolted and battled against a foreign power. For a colonizing authority like the British, who wanted to administer India as a colony rather than as a welfare state, it may even be justified. This is the primary distinction between India’s independence from British rule.

The sovereignty of the Indian state is reflected in the sovereignty of its citizens, which is intended to represent the people’s will. However, the reality is that the harsh punitive provision from the 19th century still exists in our legal code and is also applied by the state anytime it feels “uncomfortable” with particular utterances. It has evolved into a tool used by the government to quell opposition in society, whether it is directed at poets, journalists, or students, depending on the state’s whims and fancies. One violation of this legislation, even against a single individual, can have a significant impact on society and signal that no one will ever again dare to challenge the authority of the state.

The administration has no intention of acting like a welfare-democratic state; instead, it is fixated on policing. Even though these laws weren’t added until the BJP’s historic victory in 2014, it’s important to see how they are currently being repealed. Data also indicates that 47 sedition incidents were reported in 2014, 30 in 2015, 35 in 2016, 51 in 2017, 70 in 2018, and 93 in 2019, according to the data. Between the ages of 18 and 30, the bulk of individuals held under sedition laws in 2019 was detained.

The NCRB study states that while the percentage of convictions decreased to 3.3% in 2019 from 33.3% in 2016, the number of sedition cases surged by 160% between 2016 and 2019. According to the final police reports, six instances were found to be civil disputes, two were labeled “fake,” and 21 cases were dismissed due to “insufficient” evidence.

This statute demonstrates how, even in a democratic nation-state, the government still views its citizens as its greatest danger. As a result, rather than removing such laws, the government continues to employ them. The “social compact” between the citizens of a contemporary nation-state and the government is somewhat weakened by this scanning of suspects between the two fundamental pillars of the state.

The notion that the two parties must have a trusting relationship is one of the fundamental concepts of a social contract. The development of an intolerant state is shown, however, when a government begins acting like a surveillance state and employs its apparatus, such as the police and army.

Origin and evolution

According to Section 124-A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), “whoever brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection toward, the government established by law in [India], will be punished with [imprisonment for life], toward which a fine may be added, or with imprisonment that may extend to three years, to which a fine may be added.” To prevent crimes against the state, this statute was passed in 1860 during the British Raj.

The British employed sedition legislation to repress dissent and arrest freedom fighters who opposed the colonial government’s policies, including Mahatma Gandhi and Bal Gangadhar Tilak. Following Independence, the drafters of the Constitution spent a lot of time commenting on several facets of this colonial statute. K.M. Munshi was one of the most vocal opponents of the sedition legislation, claiming that such a harsh law poses a danger to India’s democracy.

He claimed that “in actuality, government criticism is the core of democracy.” The word “sedition” was removed from the Constitution as a result of the efforts and tenacity of Sikh politician Bhupinder Singh Mann.

The First Amendment, which was approved by the administration of the nation’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, however, reinstated this legislation. Nehru had said, “Now, so far as I am concerned, that particular Section (124A IPC) is highly objectionable and impolite, and it should have no place both for practical and strategic reasons if you will.”

The earlier we eliminate it, the better. He dallied on this, though, as his administration amended the first amendment in 1951 by adding the phrases “friendly relations with foreign states” and “public order” as justifications for placing “reasonable limits” on free speech.

Issues with the laws against sedition

The 1962 Kedar Nath decision said that the sedition statute should only be used in exceptional circumstances where the nation’s security and sovereignty are at risk. The evidence that this rule has been weaponized as a useful tool against political opponents to stifle criticism and free expression is nevertheless mounting.

According to the most recent statistics provided by Article 14, 25 sedition charges were filed following the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act rallies, 22 cases were filed following the gang rape in Hathras, and 27 cases were filed following the Pulwama event. In all, charges of sedition brought against 405 Indians during the past ten years were lodged after 2014 in 96 percent of those cases.

Furthermore, according to data from the National Crime Records Bureau, the number of sedition cases increased significantly (163%) from 47 in 2014 to 93 in 2019. The conversion rate from cases to convictions, however, is a meager 3%. This demonstrates how the police and other state officials are indiscriminately employing sedition laws to terrorize the populace and stifle any criticism or opposition against the dictatorship.

Flaws in the law and erroneous interpretation

One of the primary legal issues with the sedition statute is that it is inadequately defined. The phrases “incite hate or contempt” or “try to inspire disaffection” can be construed in a variety of ways, allowing the police and government to harass innocent persons who live on the other side of the barrier. Sedition legislation can be used fraudulently by authorities to charge people unfairly because it does not explicitly state which activities are seditious and provides a broad range of what might be considered seditious.

Justice D.Y. Chandrachud recently raised this point while preventing the Andhra Pradesh government from taking unfavorable action against two Telugu news networks charged under Section 124A (sedition) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). “Everything cannot be seditious,” Justice Chandrachud observed. “It is past time to define what constitutes sedition and what does not.”

In another significant case (a PIL filed against former Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah), Justice Chandrachud remarked, “Expression of opinions that are dissenting and differ from the government’s stance cannot be considered seditious.” Similarly, in the Disha Ravi case, the Delhi High Court stated unequivocally that the government cannot imprison individuals “just because they choose to disagree with state policy” and that “the charge of sedition cannot be used to minister to the wounded pride of administrations.”

These judicial opinions differ from the executive’s understanding of the sedition legislation, demonstrating how the law is being arbitrarily applied by them.

incompatible with liberty and democracy

The hallmark of a democracy, freedom of speech and expression, is being threatened by the sedition statute. Citizens must actively engage in discussions and voice their constructive criticism of government initiatives for a democracy to exist. The executive arm of the government is now able to exploit the vaguely defined provision to control public opinion and arbitrarily exercise authority, thanks to the sedition legislation. The sedition legislation is being used to encourage citizens to follow rules set out by the government.

The administration has frequently used the sedition statute to silence critics to further its objectives. Many concerns regarding freedom of speech and expression in India have been highlighted by the arrests of NDTV journalist Vinod Dua for criticizing the government’s response to COVID-19 and Disha Ravi, 22, in the Greta Thunberg toolkit case for tweeting in support of the farmer’s agitation in India. Democracy is impacted when the sedition statute is used to restrict journalists. Because the government may dismiss its critics and then accuse them of sedition, the sedition laws diminish governmental responsibility.

What is more worrying is that it may be quite challenging to obtain bail after being detained under the sedition statute since the trial process might drag on for a very long time. As a result, innocent people are harassed, and others become afraid to criticize the administration. The Hubli Kashmiri students’ cases serve as an illustration of how challenging it may be to get bail in a sedition case, as they were released on default bail after 100 days in police prison.

Sedition laws and the escalating abuse of them by all types of governments (even those run by the opposition) are a big problem. Sedition laws and their flagrant abuse undermine the entire basis of these rights, which are guaranteed by the Indian Constitution, as well as personal liberty and the right to free expression, which are characteristics of liberal democracy. The judiciary must reconsider this oppressive statute immediately due to the pressing requirement. Aside from preserving the country’s freedom of expression, modifying the legislation and providing strong restrictions to prevent its indiscriminate usage will enhance India’s democratic standing even though its total abolition may not be possible.

edited and proofread by nikita sharma