Heading For Confrontation, China’s Warning Of Retaliation Amidst The United States – China Chip War; Who Will Win The Battle Of Technological Supremacy?

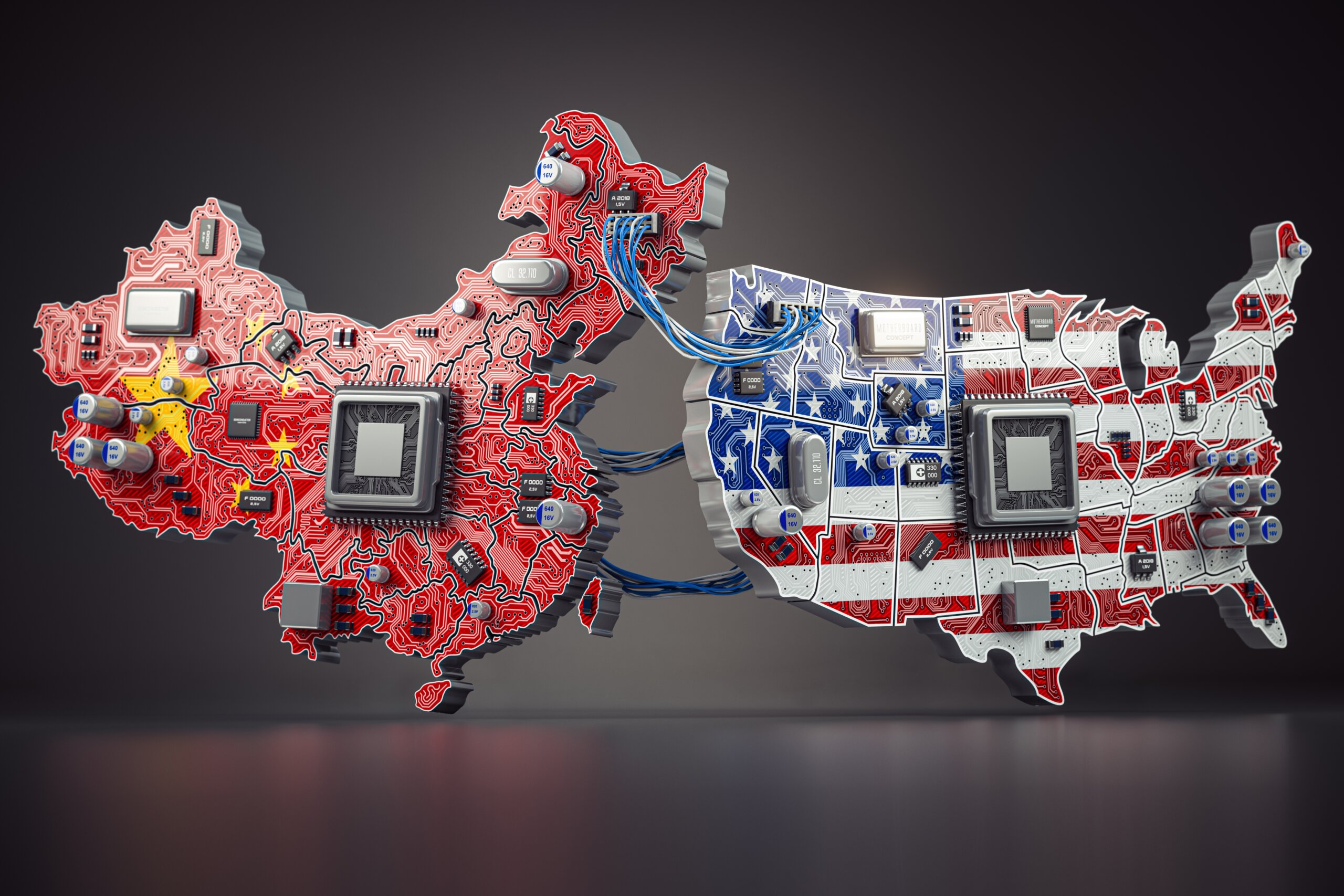

The intensifying competition between China and the United States in the semiconductor industry has sparked concerns over intellectual property and manufacturing disputes. As the U.S. strives to bolster its chip production and utilizes sanctions to hinder China's pursuit of self-reliance in this critical sector, global tensions have escalated. This conflict is centered around the semiconductor industry, a linchpin for technological advancements crucial to economic prosperity and national security. At the forefront of this battle are key players such as TSMC, Intel, and Samsung, each navigating challenges and opportunities in the pursuit of dominance in the semiconductor industry.

China has expressed concerns about the escalating tensions with the United States in semiconductor intellectual property and manufacturing.

The U.S. is actively working to revitalize its chip production capabilities, utilizing sanctions to impede China’s efforts to achieve self-reliance in this crucial industry.

The semiconductor sector, a catalyst for technological advancements like artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, and factory automation, is critical for economic prosperity and national security.

Despite the United States accounting for 25% of global semiconductor demand, its manufacturing capacity is only 12%, a significant decline from the 37% held in the 1990s. This has raised apprehensions about national security risks, particularly considering China’s endeavours to establish a substantial presence in this vital industry.

China’s Sturdy Response

In response to US chip equipment restrictions, China has hinted at the possibility of retaliation, characterizing the American approach as “hegemonic.”

Chinese Ambassador to the Netherlands, Tan Jian, emphasized that the European Union need not be entangled in China’s response to these restrictions, stressing that while China would react to hegemonic treatment, its relationship with the E.U. should remain unaffected.

The Biden administration’s efforts to curtail Beijing’s ambitions in the semiconductor industry have led to an expanded ban on certain high-end equipment sales to China, which recently took effect.

Tan Jian criticized the US, asserting that its notion of security extends excessively, even to non-military matters, and that it exerts pressure on allies to follow suit.

ASML’s cancellation of some machine shipments to China at the request of the US government has intensified the situation. The White House clarified its stance, emphasizing that the US aims to “de-risk, not de-couple” and that decisions on export licenses are tailored to safeguard national security.

In light of the complex situation, Tan Jian urged improved dialogue between China and the Dutch government to prevent further deterioration, highlighting the challenges faced by Chinese companies operating in the European Union, citing increased controls, political pressure, and disinformation as impediments.

What’s The Name Of The Game

ASML, a prominent Dutch manufacturer crucial to the global semiconductor supply chain, has reportedly halted the export of sophisticated microchip machinery to China due to pressure from the U.S. government.

The company, specializing in extreme ultraviolet lithography systems (EUVs) vital for chip production, had its export licenses revoked by the Dutch government before the scheduled shipment of three chip-making machines to China.

These advanced technologies, employing lasers to facilitate chip circuit creation, are utilized by major chip producers like Samsung and Intel. It was revealed that ASML decided to cancel the machine shipment following a request from the Biden administration.

However, a subsequent statement from the company clarified that the Dutch government had “partially revoked” a license for the shipment of two types of lithography machines, impacting a “small number of customers” in China.

ASML mentioned, “In recent discussions with the U.S. government, ASML has obtained further clarification of the scope and impact of the U.S. export control regulations.”

The move aligns with U.S. efforts to curtail China’s semiconductor knowledge and production expansion, encouraging allies to restrict technology associated with semiconductor manufacturing.

Last October, the Biden administration introduced new restrictions to block non-U.S. firms from exporting semiconductor chips and lithography machines containing U.S.-made parts and technology.

In July of the previous year, under U.S. pressure, the Dutch government imposed restrictions on the sales of ASML’s deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography machines, the second most advanced in its lineup, with these restrictions officially taking effect on Monday.

In response to the blocked ASML orders, Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin urged the Netherlands to “be impartial, respect market principles and the law, take practical actions to protect the common interests of both countries and their companies and maintain the stability of international supply chains.” He criticized the U.S. for engaging in “hegemonic and bullying behavior.”

ASML downplayed the impact of the license revocation on its financial outlook for 2023, stating that it does not expect a “material impact.”

The spokesperson highlighted the confusion in European China policy, describing China as a cooperation partner, an economic competitor, and a systemic rival.

The Unending Chip War

Reports emphasise the U.S.-China Chip War, particularly highlighting the CHIPS and Science Act, enacted into U.S. law in 2022. This legislation aims to enhance domestic chip production by allocating $52.7 billion over a five-year period for the development of domestic manufacturing, research and development (R&D), and workforce programs.

Under the CHIPS Act, semiconductor companies are eligible for a 25% investment tax credit when investing in semiconductor manufacturing or specialized tooling equipment.

However, the report underlines the challenges the CHIPS Act may encounter in translating its objectives into tangible outcomes. The Commerce Department introduced conditions in March for companies seeking $150 million or more in funding, incorporating limitations on stock buybacks, profit sharing, and a preference for union labor.

The report warns that such conditions might make it exceedingly challenging for companies to bring cutting-edge semiconductor manufacturing back to the U.S., as they strive to remain below the $150 million threshold.

The former chair and CEO of the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), a major player responsible for 90% of the world’s most advanced processor chips, estimates that producing leading-edge chips in the U.S. could cost up to 50% more than in Taiwan, attributing this to labour costs and differing worker norms.

The report notes that most semiconductor companies, being highly profitable entities globally, may not require additional funding. Consequently, it suggests that only less-profitable chip companies may be more inclined to engage with the CHIPS Act in its current form, potentially limiting its overall impact on the industry.

In the semiconductor industry, companies opting to manufacture chips in-house are referred to as Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs), and the facilities producing these chips are known as fabs.

Alternatively, some companies follow a “fabless” model, outsourcing the manufacturing process to a foundry, while others adopt a hybrid approach.

According to the Semiconductor Industry Association, the 10-year cost of constructing a state-of-the-art fab is estimated to range between $10 billion and $40 billion, a significant increase from less than $1 billion in 1997.

Only four IDMs—Samsung, Intel, Hynix, and Micron—possess the necessary scale to support the construction of leading-edge fabs. On the other hand, other semiconductor companies, such as Nvidia, AMD, Qualcomm, and Marvel, have opted to outsource some or all of their manufacturing to TSMC.

TSMC stands out as the predominant leader among the five major foundry companies, commanding a robust 58% share of the global market.

In 2021, Intel declared its intention to refocus on the foundry business, aspiring to surpass Samsung and become the second-largest foundry by 2025.

However, the authors of the report identify several impediments hindering Intel’s ambitions, such as stringent design rules, talent turnover, and the fundamental disparity between the foundry business model and Intel’s CPU business.

Simultaneously, TSMC is strategically expanding its fabs beyond Taiwan as a precautionary measure against potential disruptions in the supply chain arising from geopolitical tensions in the region.

It is anticipated that this move will enable TSMC to retain a substantial share of the foundry business, although they acknowledge challenges in establishing a leading-edge foundry in the United States.

Contrarily, Samsung’s foundry business is anticipated to benefit from the CHIPS Act, leveraging its 27 years of foundry experience in the United States.

The U.S.-China chips rivalry employs various strategies beyond the CHIPS Act, including sanctions imposed by the U.S. and its allies on China.

Originating in 2017 with U.S. actions against ZTE, the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security tightened export controls in October on advanced semiconductor production equipment and high-performance computing chips.

These restrictions have constrained China’s ability to acquire and manufacture advanced chips, particularly those utilized in supercomputing and A.I. training.

Notably, the export restrictions also impact non-U.S. vendors and exporters, prompting Japan and the Netherlands to limit their semiconductor-making technologies.

However, despite limitations, China’s advanced semiconductor fabs can still produce chips in limited volumes, potentially leading to additional sanctions.

The European Union has introduced its version of the CHIPS Act known as the European Chips Act (ECA).

With only around 10% of global chip manufacturing situated in Europe, the E.U. aims to double this figure to 20% by 2030. European and international chip makers are committing to R&D and fab expansion plans in Europe, hopeful of accessing funding from the ECA and other sources.

Unlike the CHIPS Act, the ECA lacks restrictive measures, making chip manufacturers more willing to tap into this funding opportunity.

Japan has undertaken its initiative to establish semiconductor production facilities, outlined in the 2022 Economic Security Promotion Act, which outlines a framework for combined public and private financing totaling ¥10 trillion over 10 years.

Despite accounting for 12% of global semiconductor consumption, Japan’s share of production capacity is notably low. The semiconductor industry in Japan is witnessing a surge in activity, driven by expectations of increased demand for Japanese-made chips as supply chains diversify away from Taiwan.

Japan is actively encouraging foreign companies and foreign capital to play an active role, with notable entities pursuing investment and collaboration, including TSMC subsidiaries, Taiwan-based PSMC, and U.S.-based Micron.

The Last Bit, the U.S.-China Chip War unfolds as a complex interplay of legislative initiatives, technological prowess, and geopolitical considerations.

The CHIPS and Science Act in the United States, coupled with sanctions on China, reflects the multifaceted strategies employed to secure supremacy in the semiconductor industry.

TSMC emerges as a dominant force, overcoming challenges in expanding its global footprint while Intel grapples with transforming its foundry business model.

As nations worldwide vie for semiconductor self-sufficiency, the ramifications of this chip war reverberate across economies and industries, stressing the critical importance of semiconductor technologies in the contemporary global atmosphere.