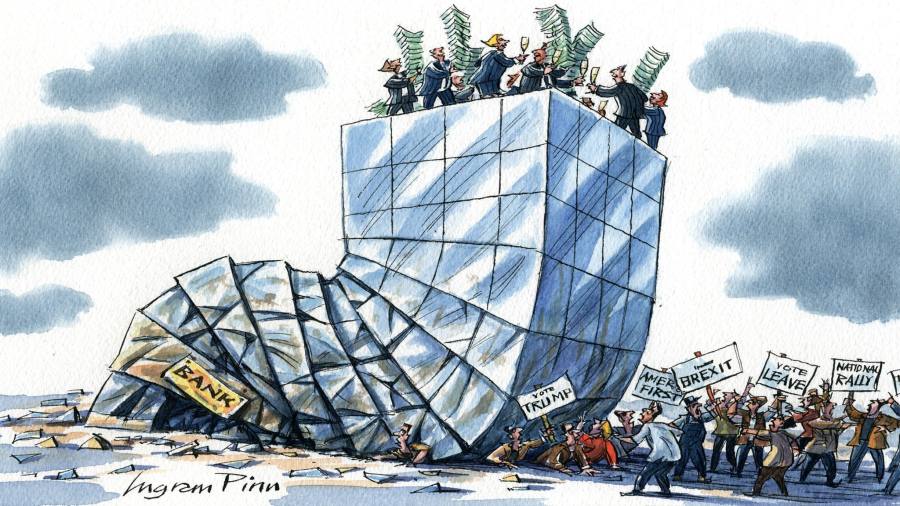

The financial disaster that troubles UK’s serves as a warning to the rest of the globe.

Politics, inflation and rising interest rates are combining to endanger the UK’s financial system, sending shock waves across international markets and alerting governments worldwide to the perils of the new economic period we are approaching.

Just over a week ago, the new British government lowered taxes unexpectedly, raising investor concerns about the country’s economic stability and causing the pound and gilt market to fall. In market reporting, superlatives are plentiful, but the unrest during the last week was remarkable.

The longest-dated gilts, which mature in 50 years, lost a third of their value in four days, in addition to the huge fluctuations in the pound. Then, following the Bank of England’s emergency bond purchases intended to stop a cycle of forced bond sales by pension funds, their value soared by more than a quarter in a single day. For comparison, the largest four-day decline in the past had been halved that amount, and the largest daily gain had been 15%, both times when pandemic lockdowns closed the economy.

Global markets were immediately impacted by such large shifts, which resulted in rising dollar and Treasury rates and falling stock and commodity prices. London usually has an unduly large influence on global markets due to its function as a significant financial center, a hub for international investors, and the fact that the sterling-dollar exchange rate is the third most traded currency pair globally. The greater concern is that the United Kingdom may serve as the canary in the coal mine, alerting other industrialized nations to impending risks.

There are three different risks. Is the UK a unique situation or just the first victim of the recently awoken bond vigilantes (investors who penalize spendthrift governments with increased borrowing rates) in the near term? Is the United Kingdom, which is expected to adopt a lax fiscal policy that increases inflationary pressure, going too far with this strategy in the long run?

The Federal Reserve is rumored to raise rates until something breaks, according to an old saying. The Fed’s part in all of this is that it helped the dollar soar by switching to much higher rates, which hurt sterling and raised global rates even before the selloff sparked by tax cuts. Something is broken right now, and perhaps other things will follow suit.

Start with the mistakes made before addressing the immediate problems. The unexpected unfunded tax reduction by the government, which benefited the wealthy the most and amounted to around 1.8% of GDP annually, served as the catalyst. It isn’t much in the grand scheme of things. But the larger context of skyrocketing interest rates, excessive debt, poor communications, and the degradation of the nation’s institutional integrity meant that the cut had such a significant impact. The majority of those problems are present in most industrialized nations, albeit to varying degrees.

Investors are nervous because interest rates are rising practically everywhere. The Bank of England must take more action because borrowing to boost the economy when inflation is in double digits and the central bank is hiking rates to try to bring things down puts monetary and fiscal policy at odds. With its €750 billion ($735 billion) Next Generation EU stimulus program just getting started, Europe has chosen to spend more rather than tax less.

After the Senate rejected President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better plans and the inflation that followed last year’s massive stimulus package, the United States has moved away from fiscal support. The Inflation Reduction Act, which is more fiscally responsible, includes elements of the previous scheme.

Due to the anticipated $140 billion ($140 billion) subsidy of energy bills for individuals and companies, from a base of 95% of GDP last year, Britain’s debt was already forecast to soar. According to the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel, that was the biggest subsidy of any nation in Europe up until Germany went even bigger on Thursday, equal to 6.5% of the UK’s GDP.

The subsidy, however, didn’t bother the markets because it was a one-time measure to counteract the increase in energy prices brought on by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; in contrast, the tax cuts and the resulting decline in government revenue are intended to be permanent, which is why there was a rush to sell.

The debt situation is made worse by the necessity of borrowing from foreigners due to Britain’s enormous current account imbalance. However, it continues to allow borrowing in its own currency, a fundamental aspect of mature markets. To tempt foreign lenders, it must, however, borrow more money, which results in a weaker currency, higher interest rates, or, as of this past week, both.

The way the tax cuts were communicated was appalling. The administration opted to not discuss the effects on public finances, instead focusing on its desire for faster development, which it said the tax cuts would contribute to.

Investors and economists couldn’t agree. After the market’s appalling response, Prime Minister Liz Truss remained mute for many days before attempting to attribute the decline in U.K. assets to external forces. Denying what any investor can perceive to be true is a bad tactic for influencing people’s opinions.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, a body that typically reviews new tax and expenditure proposals, was ignored and did not receive the customary prior examination. Ms. Truss had spent most of the summer criticizing the traditional economic approach used by the U.K. Treasury—an approach that had calmed bond markets but that she attributed to the country’s lackluster development over the previous ten years.

One of the new administration’s first actions was to fire the finance secretary, a highly rare action in the politically neutral British civil service.

The concept of a return to normalcy came after Brexit, Boris Johnson, the previous prime minister, and Brexit, Richard Robb, co-founder of investment manager Christofferson Robb & Co., with Ms. Truss, who has offices in New York and London. “Then: hold on, it’s not going back to normal.”

These issues are present in various countries in some form or another. The UK, however, serves as a warning to other governments since no other big economy has been so reckless about what the markets want. Even while Britain is the canary in the coal mine, its trembling tells other countries to handle the bond markets better.

In the long term, the answer appears more obvious: yes, inflationary pressures will increase globally in the future. The post-2010 secular stagnation, which saw weak development despite extremely low interest rates, was best exemplified by Britain. With budget cuts and a highly strict fiscal strategy, the U.K. went farther than other developed nations with austerity.

The Bank of England tried to counteract this by maintaining historically low interest rates to assist the economy. Given that her unfunded tax cuts are expected to relax the purse strings for many years to come—and result in considerably higher interest rates—Ms. Truss, who loves to compare herself to tax-cutting former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, may wind up serving as an example of the opposite strategy.

Until recently, markets did not agree and assumed that, after taking inflation into account, there would be a period of very low global interest rates similar to the period of secular stagnation that followed the 2008–2009 crises. Although inflationary pressures may be substantial, they are believed to be transient. This has changed in recent months as investors gambled that inflationary forces would drive central banks to maintain rates higher for the foreseeable future, driving up long-term real yields on U.S. Treasury inflation-protected securities.

Investors ought to be quite concerned. Holding treasuries and growth stocks, similar to the major technological firms, “may earn big profits owing to the ultra-low interest rates,” as it was first said, and “in the case of a return to the so-called “new normal,” “may make massive gains.” Treasurys and growth stocks are expected to suffer from upcoming rate increases and inflation, which will make cash the obvious victor and best “value” investment. As compared to the rest of the stock market, equities are performing well.

The most terrifying possibility is that Britain is only the first significant country to see rising rates. Financial issues were frequently brought on by previous Fed tightening cycles, most notably the global financial crisis that started with the collapse of the subprime mortgage market in 2007, but also numerous crises in emerging markets, the collapse of the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, and the implosion of the overnight borrowing market in September 2019.

As is usually the case, problems arose in a place that was deemed secure. An effort by a pension fund to lessen the impact of interest rate fluctuations was unsuccessful when rates increased and bond prices fell, further reducing expenses.

Perhaps there won’t be any more seismic incidents, and Britain’s woes will only turn out to be a small earthquake with a few casualties. Nowhere else has the precise issues that Britain does, and no other country’s policymakers have been as eager to court market anger.

I don’t anticipate anything of the same magnitude as the financial crisis. But given how difficult the situation is and how serious the threats are, I would be surprised if we made it over the next two years without seeing at least a few smaller crises and perhaps more central bank bailouts.

edited and proofread by nikita sharma