Covid’s harmful effects on the brain surfaces years later: Study 2022

Covid’s harmful effects on the brain surfaces years later: Study 2022

Many scientists were curious about how COVID-19 will affect the lungs when it first emerged. However, other people, like Ravindra Nath, medical director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, thought COVID-19 might have an essential effect on the brain. These initial theories have been verified by brain autopsy information from COVID-19 fatalities, which reveals inflammatory cells and damaged blood vessels.

Less was understood about the direct impact on the brain of those who experience Long Covid, a condition in which symptoms last for weeks after the primary infection. According to Yale University neurologist Serena Spudich, what first appeared to be a long array of neurological problems has been narrowed down into the main groups.

Search to find how scientists and medical professionals have been deciphering how COVID-19 affects the brain and researching remedies to relieve symptoms.

Several survivors have reported being at high risk for developing the most serious mental disorders and many other conditions of a similar nature for at least two years of their lives. This assumption is based on a study that highlights the highest burden of all chronic illnesses that may still exist to be a result of the pandemic.

Even though anxiety and despair are more common after Covid than after other respiratory illnesses, the risk usually disappears in two months, according to Oxford University researchers. A study published on Wednesday in the magazine Lancet Psychiatry found that longer-term cognitive and brain health concerns, like epilepsy, seizures, and cognitive deficiencies commonly known to be the “brain fog,” continued to be more prevalent 24 months later.

The results, which are based on data from more than 1.25 quarters of patients, add to mounting evidence that the virus has the potential to seriously harm the brain system and increase the burden of dementia around the world, which is estimated to have cost $1.3 trillion during the year the disease outbreak started. In March, Oxford researchers presented that even a mild instance is linked to brain shrinkage that is equal to up to ten years of healthy ageing.

“The results have big implications for both patients and medical facilities,” said Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry and the study’s lead author. “It shows that reported cases of neurodegenerative conditions linked to Covid-19 contagious diseases are likely to occur for a considerable period after the global pandemic has subsided.” He claims that the work highlights the need for more research to ascertain the reasons why this happens and what may be made to prevent and address these issues.

What Experts Know About “Long Covid” and Who Gets It

The study looked at data on 89 million people, with ages ranging from children to seniors, and de-identified data on 14 mental and neurological conditions. Throughout the two-year study, a control subject of 1.28 million new cases with another respiratory ailment acted to be the complement for the 1.28 million people with a confirmed Covid diagnosis.

In contrast to adults, children had a decreased risk of receiving most psychiatric and neurological disorders after Covid. Unlike adults, kids did not have a higher chance of developing mood or anxiety problems, and any of the cognitive impairment they did have tended to be temporary.

It is alarming.

The reason that there is no rise in the probability of these illnesses in children and that the higher risk of anxiety and depression diagnoses following Covid is rather short-lived is encouraging, according to co-author Max Taquet. However, even two years later, it is bothering because some other disorders, like dementia and seizures, are still detected more commonly following Covid.

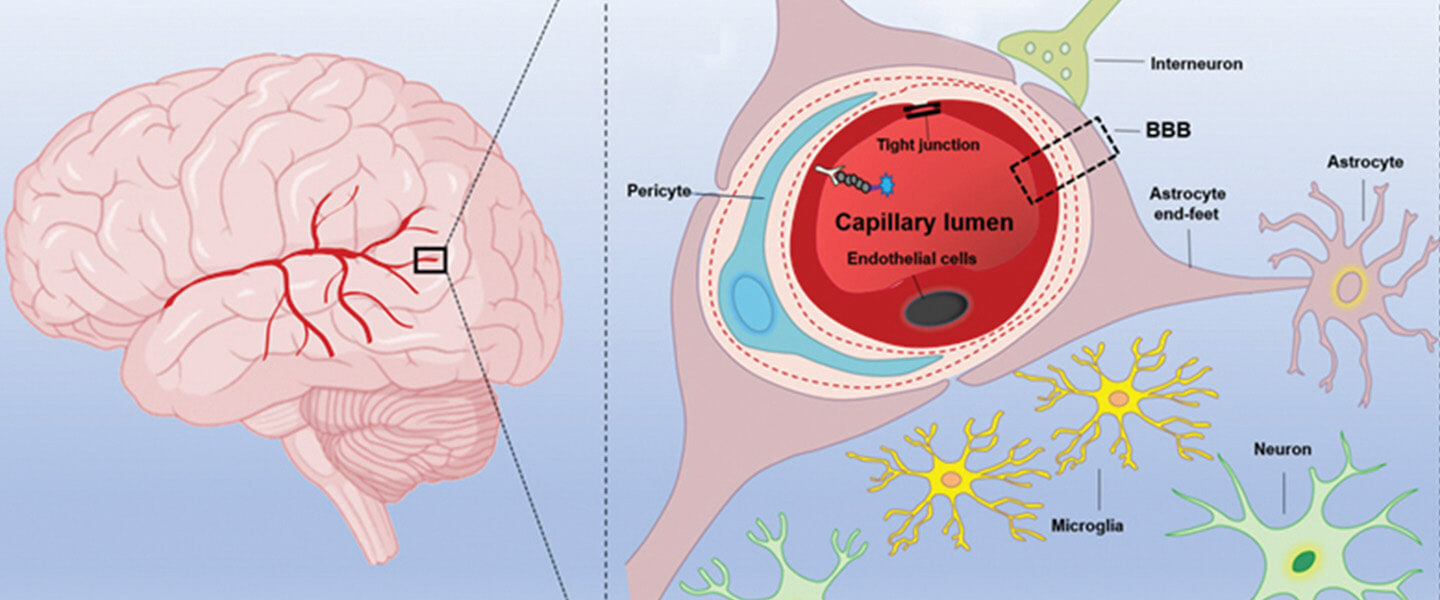

The fact that these hazards have been raised over such a prolonged period shows that the underlying mechanisms were causing them to continue long after the acute infection, according to the researchers. Blood clots and blood-brain barrier leaks are two potential causes. Blood vessel lining damage is another.

The majority of cognitive or neurological consequences, claim the authors, are related to reduced or unaffected risks from past immunization. Even after the creation of the beta and omicron variants, the prevalence of these issues maintained, indicating that coronavirus illnesses may continue to induce mental conditions even when they result in less severe diseases.

According to Glyn Lewis and Jonathan Rogers from University College London, the study is the first that attempts to look at some of the different and enduring neurological and mental effects of Covid in a sizable dataset. The authors stated that the study “highlights some clinical aspects that specifically demand further examination” and that extra studies are required to confirm the results.

Researchers in the UK have exposed that COVID-19 may have long-term brain damage and may be the reason for certain COVID-19 patients’ loss of taste and smell. Scott Gottlieb, MD, a former FDA director, stated on CNBC’s The News with Shepard Smith that the study “suggests that there may be some long-term loss of cerebral cortex from COVID, and that would have major long-term repercussions.”

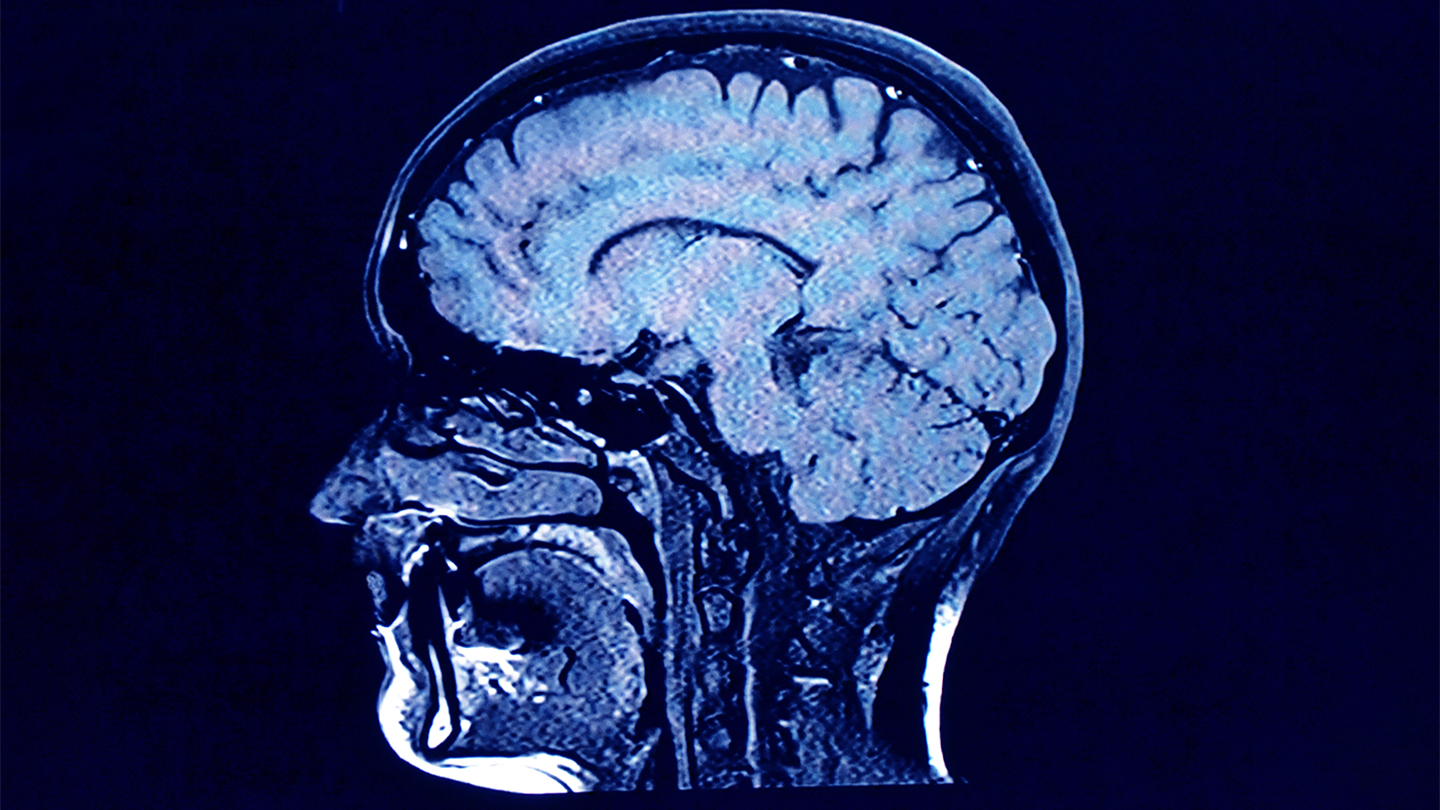

According to the study, brain imaging tests performed on around 40,000 people before the coronavirus pandemic began were accessible to scientists in the United Kingdom. They have requested the return of hundreds of those people in 2021 for additional brain imaging. Nearly 800 people gave their opinions. Of those people, 404 had COVID-19 testing results that were positive, and 394 had brain imaging that was both before and after the epidemic was still useful.

The areas of the brain responsible for smell and taste showed “significant repercussions of COVID-19 in the brains with a decrease of grey matter” when the initial planning brain scans were reviewed.

The main or second cortical skill that is developed and sensory regions in the left hemisphere are where the study identified “all relevant results using grey matter metrics (volume, thickness). A loss of smell and taste is one of the symptoms of a COVID-19 sickness. According to research, it can last for up to five months after the infection first manifests.

Millions of people around the world have now perished to be the result of the SARS-CoV-2 global epidemic. The effects of slight COVID-19 over the long term have drawn more attention from the medical and scientific communities.

The following are some pieces of compelling evidence concerning brain disorders, some of which may be brought on by viral systems that facilitate malware-induced neuroinflammation. The neurological symptoms are visible in more than 80% of the most serious forms, which is supported by radiographs and post-mortem tissue examinations. This shows that COVID-19 has impacted the brain and could have been circulating in the nerves. Patients may have cognitive problems.

In particular, the disruption in olfaction and gustatory in COVID-19 patients is a constant clinical characteristic that can manifest before the start of respiratory symptoms. In a recent study, 100% of those with chronic illness and 86% of those with or more hypogeusia showed signs of gustatory dysfunction (hypogeusia).

Grey matter loss in olfactory-related brain areas could result from such a loss of acute olfactory input to the brain19. Olfactory cells, either supporting or neuronal, which are collected in the olfactory bulb, are especially sensitive to coronavirus penetration, and this appears to be the case, specifically with SARS-CoV.

The maximum of COVID-19 brain imaging studies to date have focused on acute cases and radiological news stories of single cases or case series using tomography ( ct (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. White matter enhanced, hypoperfusion, and indications of ischemic events all through the brain, but more often in the cerebrum, have all been identified to be gross cerebral abnormalities in these studies.

With the probable exception of the ganglia and the middle or posterolateral cerebral artery areas, the majority of participants in one or two bigger studies that employed CT or MRI to check for brain injury in their patients presented no evident abnormalities and, more critically, showed no spatially defined propensity.

Imaging cohorts of COVID-19, which compare the participant data quantitatively by automated preprocessing and image co-alignment, are substantially more uncommon. In the case of people with COVID-19 who were diagnosed in a subacute stage and had fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) hypometabolism.

For a moment, frontoparietal involvement was seen, according to a recent PET cohort research based on correlates of cognitive impairment. Another glucose PET scan exposed a unilateral slow pace in the right lateral reticular formation and the lateral orbital rectus.

In over 50 previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients, a multiorgan neuroimaging study26 (and its brain-focused follow-up study27) found minor T2* anomalies in the left and right thalami when compared to matched controls. It is yet uncertain, though, if any of these anomalies existed before SARS-CoV-2 infection. Instead of being a result of the COVID-19 illness process, these consequences could be linked to a pre-existing enhanced brain susceptibility to the harmful effects of COVID-19 and/or a big propensity to display more pronounced symptoms.

We employed a longitudinal design with the data from this sizable, multifunctional brain imaging study, where participants had already been checked to be the part of UK Biobank before contracting the disease.

After some of them either possessed COVID-19 medical and public data or had tested diagnostic for SARS-CoV-2 times using fast antibody tests, they were photographed once more, on the median of 38 months later. Then, those subjects were paired with control people who had gone through the same continuous imaging process but had come back negative using the quick antigen test or had no history of COVID-19.

This study had 384 control people matched in age, sex, ethnicity, and time between the two scans and 401 people with SARS-CoV-2 infection who had useable camera images at both periods. These big numbers may allow us to identify minor but recurrent geographically distributed areas of infection-related damage, highlighting in vivo potential disease-effects spreading pathways across the brain.

Therefore, the following was the general strategy used in this study: (1) use brain imaging data from 785 people involved who visited the UK Biobank image processing centres for two scanning meetings, on average three years apart, with 401 of these having contracted SARS-CoV-2 between their two scans; (2) estimate, from every of the participant’s multimodal brain imaging data.

Hundreds of different brain imaging-derived phenotypic traits (IDPs), each of which is a measure of one aspect of the brain, the framework or function; (3) model befuddling effects, and estimate the relative contribution of confounding factors. (4) Identify important SARS-CoV-2 comparisons with the control subgroup variations in these intricacies, accounting for multiple comparison tests across IDPs, and estimate the long-term change in IDPs between both the two scans.

It did this for both an exploration set of analyses taking into account a much larger number of IDPs that covered the entire brain and a focused set of scientific theory IDPs, evaluating the assumption that olfaction is especially susceptible in COVID-19.

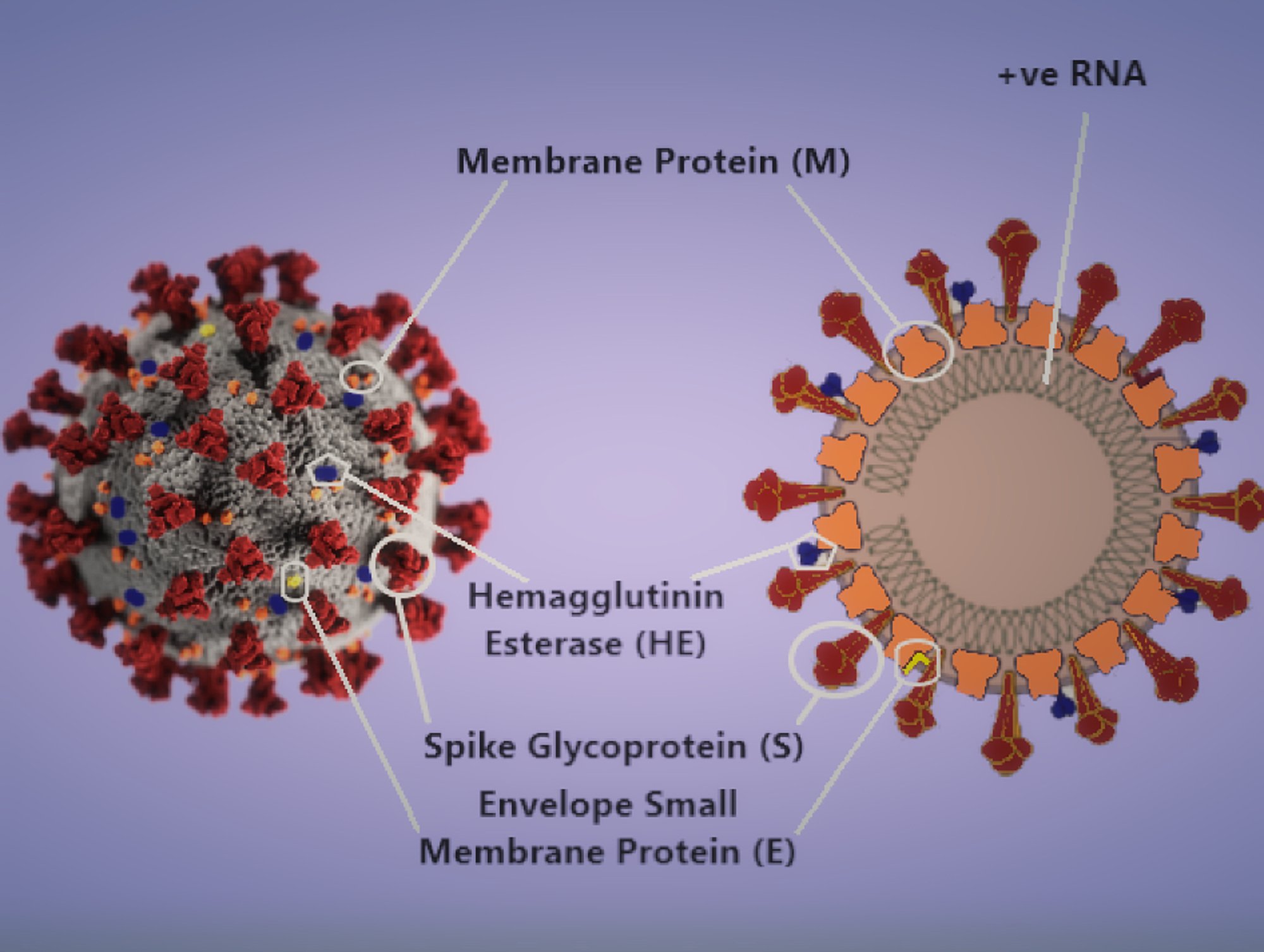

The global community was interested in the 2019 Corona Virus Infection (COVID-19) pandemic that started in Wuhan, China, in December (Thompson, 2020). Coronavirus 2 extremely severe acute syndrome is the name of the virus (SARS-CoV-2).

Patients with severe conditions are more likely to experience neurological symptoms than those with mild or mild diseases (Mao et al., 2020). Additionally, post-mortem studies on deceased patients showed partial neuronal degeneration and edema in the brain tissue (Xu et al., 2020).

Additionally, on March 4, 2020, Beijing Ditan Hospital opened a case of viral encephalitis brought on by a brand-new coronavirus (CoV) that attacked the central nervous system for the first time (CNS). By genome sequencing, the researchers checked the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in the cerebral fluid.

It presented the potential for COVID-19 to harm the neurological system (Xiang et al., 2020). Making practitioners aware of the effects of different CoV diseases on the CNS is especially important in the situation of the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic. This article examines the epidemiology, probable neuroinvasion processes, and treatment options for CoV infections that may affect the neurological system.

The term “brain fog” is not an understood medical term. However, it accurately represents a lack of clarity of thought that can occur to be the result of multiple sclerosis, cancer, or chronic exhaustion. The illness recently made attention due to claims that it affects people who are recovering from COVID-19.

The symptoms of COVID that affect the brain extend beyond the simple mental fog. They span a spectrum that includes odour and taste abnormalities and headaches, anxiety, sadness, hallucinations, and vivid dreams. Seizures and strokes included. According to one study, neurological problems affected more than 80% of COVID patients.

The Society for Neuroscience (SFN) 50th annual meeting is taking place virtually this month after a pandemic hiatus in 2020. Several as-yet unpublished research discoveries on the COVID-causing SARS-COV-2 virus’s entire journey in the brain—from gained major traction to the dispersion in brain areas to interruption of complete input presented.

Since the cell surfaces of nerve cells do not appear to have the structural anchor points needed for a forceful incursion into the cell core—like those in lung tissue, for example—researchers have struggled to pinpoint the virus’s point of entry into these cells. An article that appeared in Science the other year mentioned yet another potential point of entry. It presented how the furin enzyme interacts with the NRP1 receptors, which are located in the nerve cells of the brain and the olfactory tract, to allow the entrance of viruses.

It was still unclear, though, if this was the preferred entrance to a cell. A computer analysis of gene and protein data found the presence of NRP1 and furin on cells in some areas of the brain, specifically the hippocampus, the main memory and learning locus, according to research presented at an SFN 2021 press briefing by scientists from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences-Patna.

The peripheral nerve system, which carries sensory and motor signals from muscles, organs, and skin to the spinal cord and brain, may serve as another doorway. A mouse model of SARS-COV-2 infection was employed, and Jonathan Joyce, a doctorate student in Andrea Bertke’s lab at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, explained how his research team prepared the viral RNA (instructions for creating proteins), viral proteins, and the virus itself after the infection.

They were ensnared in groups of the nervous system that had not previously been thought to be potential entry locations. Some links went out to different parts of the brain from these groups of nerves. According to Joyce, “These channels may be employed by SARS-COV-2 to enter the brain,” and they could assist to explain the tingling and pain in some COVID patients’ nerves.

There is by no means the proper agreement on what exactly happens when a virus invades the brain. During a separate SFN 2021 press conference, Walter J. Koroshetz, head of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, stated that there is “controversial” proof that SARS-COV-2 has infected neurons.

Koroshetz added that if he were the director of the NIH, he “would probably bail and say we’ll have to see how the facts come out in the end.” Other studies have hypothesized that the neurological symptoms of COVID could be brought on by inflammation, blood-brain barrier leaking, or mucosal cell death in the nose’s mucosa, which would then kill neighbouring neurons.

Edited by Prakriti Arora