Byju’s failure to publish accounts prompts scrutiny of edtech giant

Byju’s failure to publish accounts prompts scrutiny of edtech giant

In the wake of India’s most valuable startup’s rapid expansion, investors and government officials are concerned.

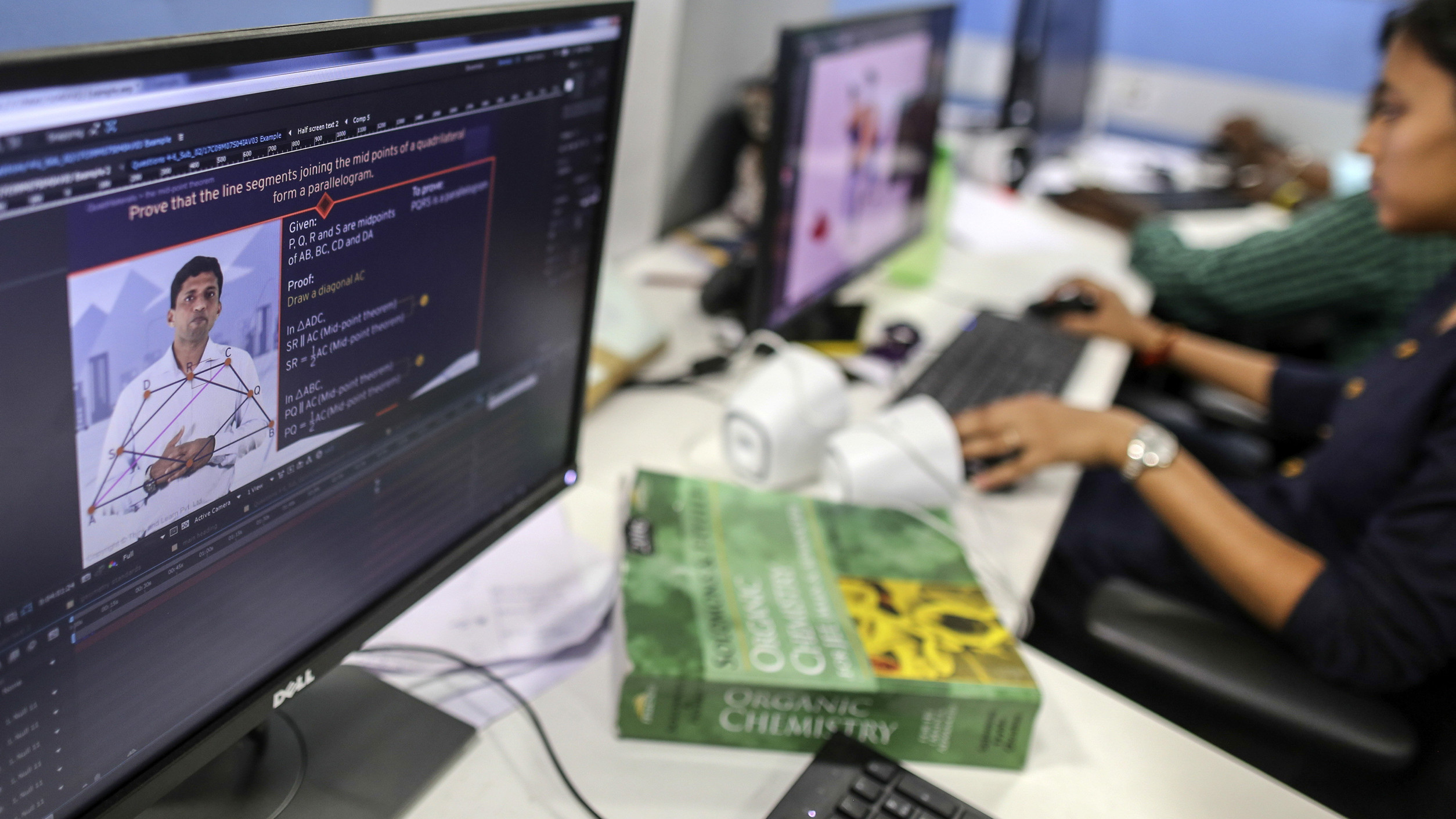

Due to repeated failures to publish its accounts, Byju’s, India’s most valued start-up, is under scrutiny from the government, investors, and creditors as financing and revenues for the once-burgeoning educational technology sector dry up. After collecting over $6 billion from investors over numerous rounds, including renowned private equity firms General Atlantic and Tiger Global, the online teaching company, which benefitted from stay-at-home Covid limitations, is now valued at $22 billion.

Furthermore, it has borrowed $1.8 billion. According to those with knowledge of the situation, the startup with its Bangalore headquarters has not yet received money totalling at least $250 million from two investors.

Additionally, it hasn’t submitted its data by the deadline for its fiscal year, which ends in March 2021. The corporation was questioned by India’s Ministry of Corporate Affairs last month over the approximately 18-month delay. In response to a request for comment about Byju’s noncompliance, the ministry remained silent.

Byju has claimed time and time again that the intricacy of reporting the more than $1.1 billion in acquisitions it made during the 2021 fiscal year prevented its auditor, Deloitte, from approving its financial statements. Two investors questioned its quick foreign expansion and aggressive acquisition approach after being contacted by the Financial Times.

As kids return to traditional schools and as India and other nations leave the pandemic, the edtech industry is being hammered particularly hard. Former and present workers of Byju’s said that the firm decreased people and finances this year in several departments, despite claims that it was still a “net hirer” from the company. Neha Singh, the co-founder of Indian data company Tracxn, said that other [edtech] firms besides Byju’s have seen an impact as a result of our opening and people going back to traditional institutions. In July 2020, Byju’s bought out Whitehat Jr.

Byju’s was reportedly in discussions to go public in the US as recently as last December. This would have involved a merger with Spac, a firm that writes blank checks, and would have been supervised by Michael Klein’s Churchill Capital.

Since then, attitudes toward startups and Spacs have significantly shifted. According to Tracxn statistics, in the third quarter of 2021, financing for Indian start-ups reached a new high of $14.8 billion. But as the economy deteriorated, financing fell by three-quarters, reaching only $6.8 billion in the second quarter of 2022, a 31% decrease from the same period in the previous year. Byju Raveendran, a co-founder, spearheaded the financing of his company’s most recent capital round with a personal contribution, which was an unprecedented move.

Like many new businesses, Byju’s parent organization, Think & Learn Private Limited, is struggling to make money. Losses were estimated at Rs2.6bn ($32.5mn) in the company’s most recent public reports for the fiscal year that ended in March 2020. Its primary source of income was the “selling of educational tablets and SD cards,” which brought in Rs16.8 billion. Markets and creditors are growing apprehensive due to the absence of performance updates. According to Bloomberg statistics, a $1.2 billion loan that the business raised in November was trading at barely 69 cents on the dollar on Wednesday following a sell-off that began in April but accelerated this week.

The charming former teacher Raveendran became one of India’s youngest billionaires when the firm he founded in 2011 experienced a meteoric rise in value. According to Tracxn, Byju’s first offered pre-recorded English classes in India before fast expanding to Southeast Asia, the US, and Latin America while purchasing 20 Indian and international edtech start-ups.

The company’s worth increased as a result of the hypergrowth strategy, rising to $22 billion at the time of the most recent investment round in March from just $5.5 billion before the pandemic in mid-2019.

The quantity of acquisitions, however, has raised worries from two investors, who hypothesized that Byju’s was trying to “buy revenues” to support its high value as the pandemic wave subsided and demand fell. “I’m not sure why they feel the need to acquire so many companies. I believe their primary business will succeed in India, but I’m not sure if their business model is successful abroad “a long-term investor who requested anonymity to talk about a portfolio company said.

A firm of our size needs to decide whether to “build or buy” when it enters a new market or region, Byju told the Financial Times. It said that since the acquisition three years ago, Osmo’s revenues, a maker of educational games, had increased five times.

The foreign growth was scaled back and budgets were reduced by more than 50% in certain areas after Byju’s funding did not materialize fully this year, according to a former operations executive. Dozens of employees in India who worked on the project were also let go without much notice. It was deemed “inaccurate” by Byju that there had been huge layoffs. According to the statement, which added that it had hired 3,000 workers in the previous year, “although there have been significant cuts in a few areas, there have also been substantial gains in employment in many other departments.

The start-up reported that first-quarter sales for the current fiscal year had increased by 50% year over year and that it planned to announce “annual financial results” this week. It claimed that by expanding into in-person seminars and courses through its subsidiary Aakash, it had shielded itself from the internet slump. Whole-spectrum education majors like Byju’s are continuing to expand, it claimed, while pure-play edtech firms are facing a correction following the pandemic surge.