Here’s Why Ambani and Adani Won’t Step on Each Other’s Toes 2023

Here’s Why Ambani and Adani Won’t Step on Each Other’s Toes 2023

In the complex tapestry of Indian business, Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani prominently feature as pinnacles of success and wealth.

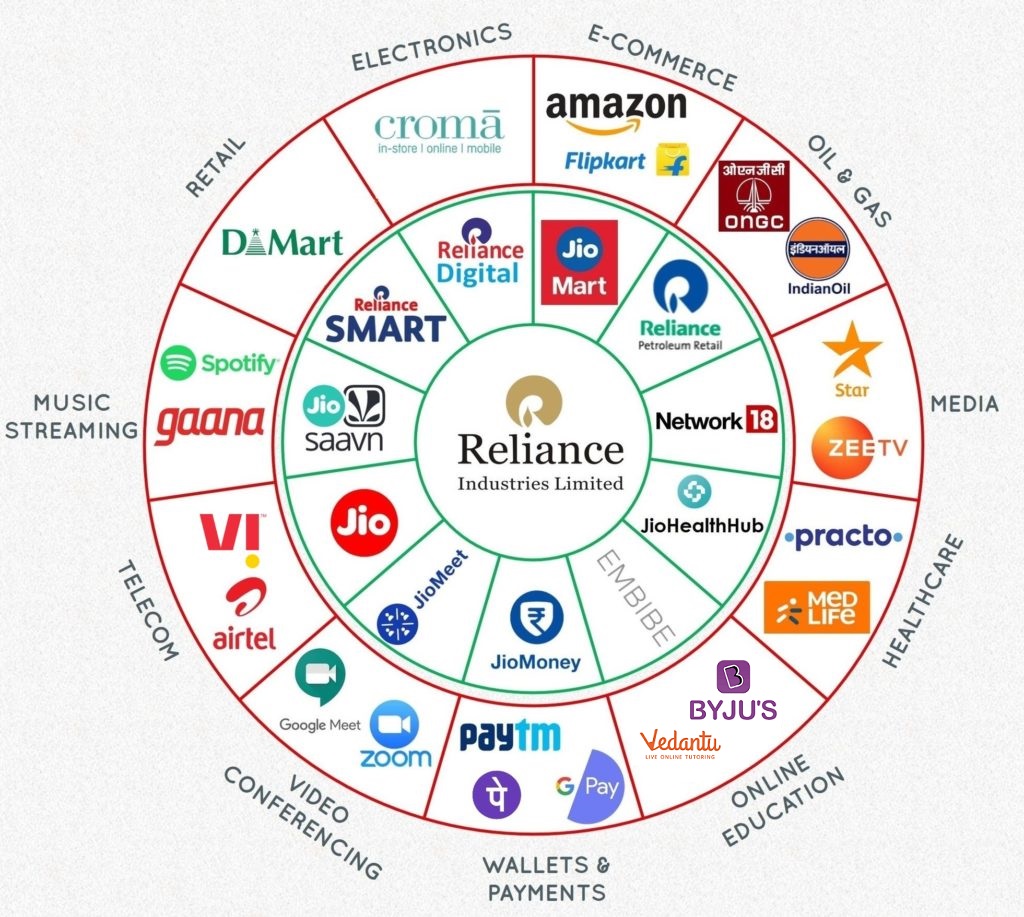

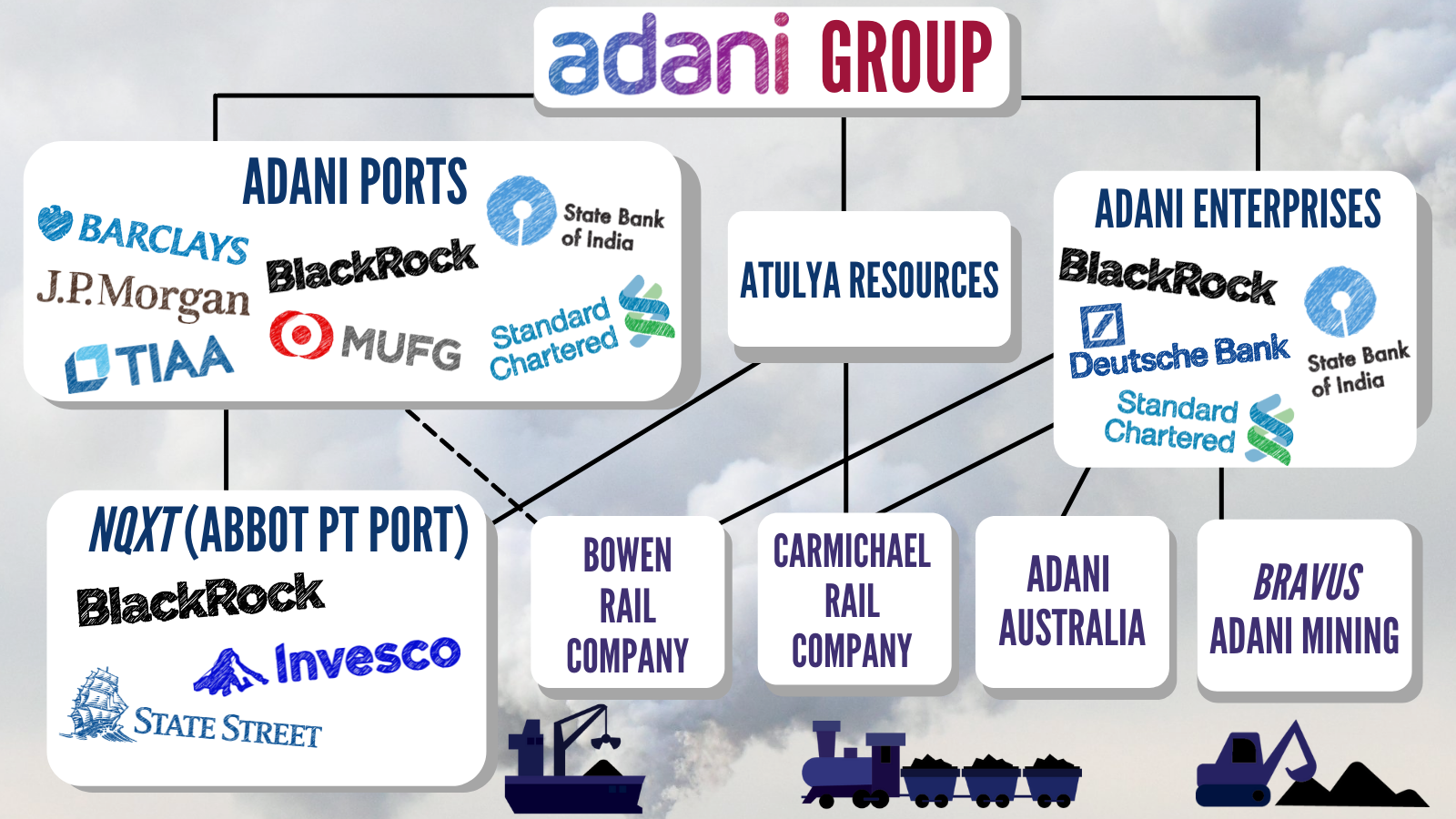

Leading Reliance Industries and Adani Group, respectively, these titans have constructed vast empires that touch numerous sectors, from energy and infrastructure to telecommunications and retail. Despite their overlapping business interests, they have maintained an unusual harmony within India’s fiercely competitive corporate environment.

In the intricate world of Indian business moguls, Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani often stand out for their extraordinary wealth and widespread influence.

These titans, leading the Reliance Industries and Adani Group, respectively, have carved vast empires that span numerous sectors, from energy and infrastructure to telecommunications and retail.

At a casual glance, these conglomerates can be on a collision course, competing fiercely for market supremacy in one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. Yet, despite having sizable and somewhat overlapping business interests, Ambani and Adani remarkably maintain a harmonious coexistence in India’s fiercely competitive corporate landscape.

This defies the expectation that such colossal entities, in their quests for expansion, would inevitably clash in brutal showdowns over market share and influence.

What explains this unspoken détente between two of India’s most influential business figures? Is it a result of a conscious effort to avoid mutual destruction, or is it born out of a strategic alignment of their interests and visions for India’s future? Is there an underlying network of political and social relationships that dictate the boundaries within which these conglomerates operate? Or is it a pragmatic recognition that India’s vast and diverse market has room enough for both giants to thrive without stepping on each other’s toes?

We will delve into the intricate web of factors contributing to this seemingly harmonious relationship between the Ambani and Adani empires.

We will explore their histories, business strategies’ evolution, relationships with political establishments, and approaches to international partnerships and ventures. Additionally, we will examine the subtle but significant ways in which they differentiate their operations to avoid direct and destructive competition and how they have sometimes even complemented each other’s growth trajectories.

Join us as we unravel the complex dynamics between these two giants, and unveil why, in a world where corporate battles are the norm, Ambani and Adani won’t step on each other’s toes.

A pricey diversion is unaffordable to Gautam Adani. Even while his primary infrastructure company is flourishing, the Adani Group has been plagued by governance problems ever since charges made by the New York-based Hindenburg Research.

An Indian billionaire under pressure is reshaping his business to avoid conflict with his larger competitor. That could be a wise course of action. A pricey diversion is unaffordable to Gautam Adani. Despite the success of his primary infrastructure company, the Adani Group has been plagued by governance problems ever since New York-based Hindenburg Research accused it of stock-price manipulation and hidden related-party transactions early this year. Even though the corporation has vehemently denied the short-seller’s allegation, its market value has fallen by more than $100 billion since January.

The June quarter figures revealed record revenue and operational profit; Deloitte Haskins & Sells LLP, the port unit’s auditor, unexpectedly quit on Saturday. Deloitte stated in its full-year audit released on May 30 that an independent external investigation was necessary since the company’s legal advice about the validity of Hindenburg’s claims was insufficient. These worries were underlined in the accountancy firm’s quarterly evaluation from August 8.

The auditor’s departure is a timely reminder that although expansion will stifle governance worries, it won’t eliminate them. India’s market watchdog requested an additional 15 days from the Supreme Court in New Delhi on Monday to complete its investigation into the firm.

The Securities and Exchange Board of India is looking into probable violations of the laws governing related-party transactions, minimum public ownership requirements, and stock price manipulation. The Adani family has raised billions of dollars to maintain investor faith. The corporation has also intensified its growth efforts by acquiring a cement firm and declaring a $3.7 billion capital investment plan for the current fiscal year.

But probably most significantly, Adani has let Ambani know he no longer wants a frontal clash.

At this time last year, the two business moguls would face off across a wide range of industries, including petrochemicals, renewable energy, communications, media, consumer goods, and banking. That danger is fading. Adani is selling his consumer finance business to Bain Capital. He was getting ready to go public with it last year. Ambani recently made a big impression in this sector by separating Jio Financial Services Ltd. from his parent company Reliance Industries Ltd. and establishing a partnership with BlackRock Inc. for asset management.

Adani may also reduce his super-app goal by withdrawing from the consumer banking sector. This move might prevent another possible dispute with Ambani’s digital business, Jio Platforms Ltd.

According to a separate story from Bloomberg News, Adani is considering selling his $2.6 billion stake in Adani Wilmar Ltd., which owns a famous cooking oil brand. Any action the organization has declined to comment on may have two objectives.

The money raised may be better used to upgrade vital infrastructure, including the fast-expanding electricity transmission unit, which requires new stock. By leaving the consumer-focused industry, Adani would be ready to cede the market to his rival. Ambani, India’s biggest retailer, wants to enter the branded consumer products market aggressively.

Last but not least, the most recent post-earnings conference call of Adani Enterprises Ltd., the group’s beachhead for expanding into new sectors, provided the most significant indication that two of Asia’s wealthiest men are headed towards at least a détente.

The chief financial officer provided a summary of this year’s capital spending plan: $1.7 billion will go towards highways, $1.1 billion will go towards airports, $300 million will go towards green hydrogen, $200 million will go towards data centres, $200 million will go towards finishing a new copper smelter, and less than $100 million would go towards water.

The initiative for coal-to-plastics should have been included in this list. The firm has refuted media rumours that it had placed the project, which was perceived as a direct threat to the Ambani group’s legacy petrochemicals sector, on hold during the height of the post-Hindenburg slump in Adani’s stock prices.

In March, the firm had stated that it hoped to reach a financial close within the next six months, at which point full-fledged procurement and construction would start. Although the organization insists that the $4 billion project is ongoing, little has been accomplished since then. On the conference call on August 3, CFO Jugeshinder Singh stated, “We are just going through the different reports preparation, site work, etc. After the results of this quarter, he promised an update.

When they enter their non-overlapping orbits, clean energy may still be a topic of interest for both Ambani, 66, and Adani, 61. However, Adani may focus on deploying his anticipated 45 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity by the decade’s end to generate affordable green hydrogen for use in steel factories, ammonia, urea, and methanol. After France’s TotalEnergies SE put its involvement on hold in response to the Hindenburg claims, the business, which will shortly begin work on electrolyzer production to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, is preparing to fly solo on the entire $50 billion green H2 project.

Ambani’s course may take a slightly different turn. Reliance’s oil-to-chemicals facility is one of the primary consumers of dirty or grey hydrogen made from petcoke, a substantial refinery waste. Ambani’s main difficulty will be transitioning to a non-polluting feedstock without sacrificing profitability. He would also try to reduce part of India’s need for motor gasoline. However, according to industry analysts, it would take years for India’s long-haul trucks and intercity buses to switch to green H2. This is related to Reliance’s fuel-retailing joint venture with BP Plc.

The likelihood of a head-on collision had significantly decreased from the previous year when the younger entrepreneur surpassed his more seasoned competitor in the worldwide wealth rankings. Adani is still the second-richest business ruler in India, but with a post-Hindenburg net worth of $62 billion, he trails Ambani by a third in terms of wealth. At least for their investors, that’s fortunate. Given that Adani and Ambani have plenty of potential to grow in India’s consumer economy and infrastructure, it would be a good idea for the billionaires to avoid stomping on one other’s toes.

Ambani and Adani emerged from different backgrounds, with Ambani inheriting a business dynasty started by his father, while Adani, a first-generation entrepreneur, built his empire from the ground up.

Historically, their focus was distinct—Ambani’s Reliance was more entrenched in petrochemicals and refining, while Adani’s roots were in global trade and logistics. These differences in origin and initial sectors allowed them to grow without significant friction.

Ambani’s Reliance has evolved to have a significant presence in telecommunications with Jio, retail with Reliance Retail, and digital platforms. Adani’s conglomerate is heavily invested in ports, logistics, agribusiness, power, and, more recently, data centres and airports. Their diversification paths show a strategic avoidance of each other’s core strengths. For instance, while Adani has ventured into renewable energy, Reliance has announced plans for a green energy giga complex, avoiding direct competition by differentiating within the same sector.

Both business giants maintain robust relationships with the political establishment. While both have demonstrated an ability to work closely with whichever political party is in power, neither has openly opposed the other or used political channels to undercut the other’s business, suggesting an unspoken agreement or understanding between the two.

Instances of collaboration between Ambani and Adani also highlight their complementary business approach. For example, Adani Ports has handled cargo shipments for Reliance Industries, and there have been talks of potential partnerships in the renewable energy space. Such collaborations reveal a strategic choice to pool resources and expertise rather than engage in wasteful competition.

India is a vast and rapidly growing market with immense potential. The sheer size and diversity of the market allow both conglomerates to expand aggressively without necessarily intruding on each other’s territory. Their significant but distinct contributions to India’s economic growth could explain why their competitive spirits have remained in check.

Ambani and Adani also have different approaches to international expansion. Ambani’s Reliance has recently attracted global investment, notably from tech giants like Facebook and Google. Adani, meanwhile, has aggressively expanded port and coal mining operations internationally, particularly in Australia. Their varied international focuses further minimize direct clashes.

Both Ambani and Adani are seasoned business leaders. They understand that a protracted battle between their groups could damage their businesses and India’s economy. It is likely that they both pragmatically recognize the wisdom in peaceful coexistence, given their aligned interests in a prosperous India.

In a world where corporate wars are commonplace, the harmonious relationship between Ambani and Adani stands as a notable exception. Their histories, strategically divergent paths, political acumen, collaborative undertakings, and pragmatic recognition of the vast potential of the Indian market all contribute to this equilibrium. As they continue to carve their legacies, both appear committed to building a brighter, more prosperous future for India—without stepping on each other’s toes.

Their story is a profound lesson in how fierce competitors can coexist, grow, and thrive by understanding and respecting each other’s paths and visions. Observing how this dynamic evolves as India’s economic landscape transforms will be interesting.