The 2022 elections could decide Narendra Modi’s fate in India’s largest state

Uttar Pradesh begins its elections on Thursday, February 10. The stakes are high. The population of Uttar Pradesh would make it one of the most populous countries in the world if it were a country. Approximately 15 per cent of seats in India’s lower house of parliament come from votes in the state.

According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Director of the South Asia program, Milan Vaishnav, India’s most significant political prize to date, barring a general election.

It is believed that the upcoming elections reflect broader sectarian tensions when Prime Minister Narendra Modi is midway through his second term in office. The Modi administration has also received criticism for how it handled the pandemic, which has killed over 500,000 people and led to the collapse of the health care system.

“The Indian public views the elections as a referendum on his rule,” Vaishnav says — particularly on Modi’s Hindu nationalist agenda.

In India’s Muslim minority, hate speech and disinformation have risen under the BJP’s watch. Hindu hardliners have openly called for an anti-Muslim genocide, and lynchings and attacks on Muslims are widespread in Uttar Pradesh and across India. Jammu and Kashmir, the country’s only Muslim-majority state, threaten to lose its historic autonomy following a discriminatory law passed by the Indian parliament in December.

Yogi Adityanath, politician-cleric and chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, has threatened to kill someone playing with the honour of Hindu women who mingles with other faiths. At Ayodhya, in eastern Uttar Pradesh, there are also plans to build a temple on the site of the destroyed mosque.

According to Delhi journalist Dhrubo Jyoti, a contributor to The Hindustan Times, the city is home to these Hindu holy sites, which in many ways have served as the nerve centre of the BJP’s Hindu politics. According to the BJP, if it fails to retain this state, it would be a symbolic defeat for the Hindutva agenda, at the very least.

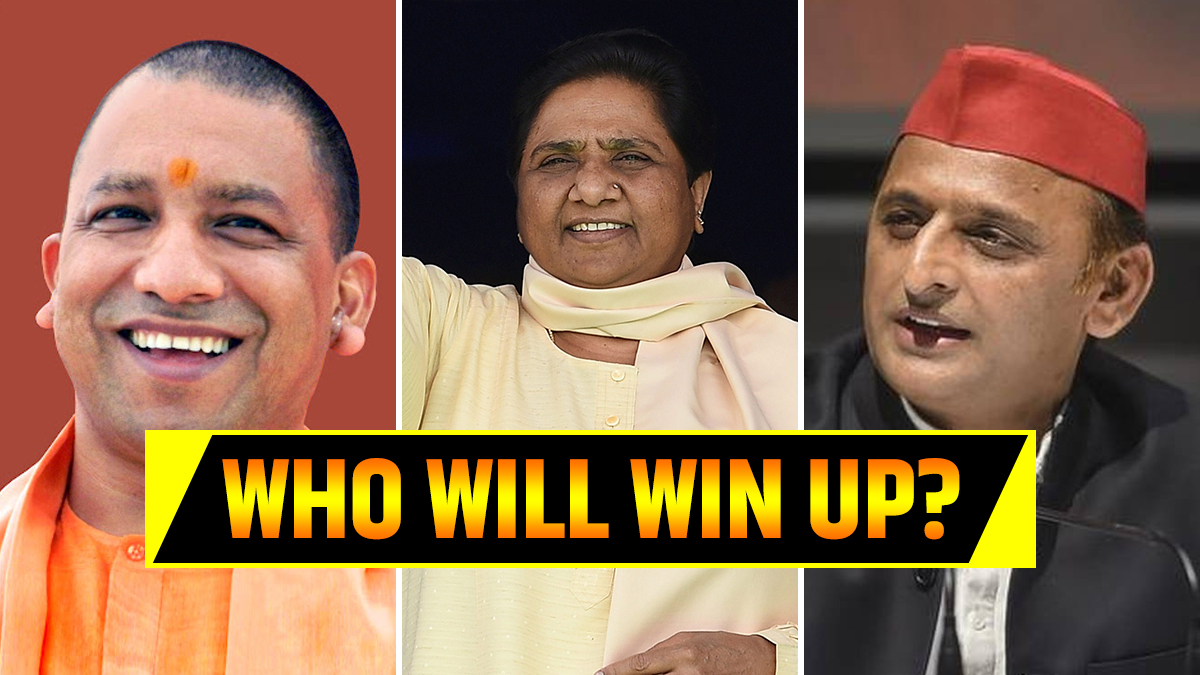

Who will run, and who will do well?

In Uttar Pradesh, where the BJP is currently in power, analysts expect it will win again with a narrower margin. However, analysts say that shouldn’t pose a problem given the extent of its previous victory. On March 10, ballots will be counted after voting has been phased out over the last few weeks.

The 2014 and 2019 national elections and the 2017 state elections were easily won by the BJP. According to Neelanjan Sircar of the Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research, “The BJP is so far ahead that it can lose a significant amount of votes and still prevail.” Sircar spent time in Uttar Pradesh as part of his research into voting trends and reports that so far, his research shows a shift away from the BJP, although it’s too early to tell if the race will be competitive.

The Samajwadi Party, led by Akhilesh Yadav, is the primary opponent of the BJP in Uttar Pradesh. Compared to rivals, the former chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, 48, has proven to be a more effective politician.

The people who dislike the BJP are looking for a party that will combine the Hindu vote with the Muslim vote to get the most votes, says Vaishnav. Samajwadi Party, which has long drawn support from disadvantaged minorities, is most likely to achieve this goal, compared to the centre-right and long-established Congress Party (INC).

It has worked hard to form alliances with smaller parties. These alliances may prove helpful for the Samajwadi Party. A few thousand votes can mean a lot in a state with many communities, says Jyoti.

Who is the current minister?

Yogi Adityanath is a Hindu hardliner from Uttar Pradesh who campaigned aggressively for the BJP in 2017 and was subsequently appointed by Prime Minister Modi, even though he lacks experience in government.

As a Hindu vigilante who used violence and intimidation against the minority community, he became famous for riling up the Hindu base and demonizing Muslims,” Vaishnav says.

Adityanath pursued Hindu supremacist policies during his tenure. These policies included renaming cities and towns that were Persian or Islamic in origin with Hindu names, whitewashing Mughal history in textbooks, and banning “Love Jihad” — the supposed conversion of Hindu women to Islam through marriage to Muslim men, in a bid to tilt the demographic balance in favour of Islam. No basis exists for the notion, which is a Hindu conspiracy theory.

According to political analysts, a victory in the state election will be viewed by the BJP as an endorsement of its heavy-handed tactics. Sircar argues that in the future, the ruling party might see Adityanath’s approach as “the model for a successful chief minister.”

In addition to cementing Adityanath’s political future, a BJP victory would also boost his popularity. Among BJP leaders, Yogi Adityanath will become the third tallest leader after Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah if the BJP wins Uttar Pradesh-and particularly if it holds a decisive majority.

Yogi Adityanath has been speculated as to the next leader of Uttar Pradesh and India as a whole.

What are the most pressing issues?

Voters will likely be most concerned about sectarian issues. In India, there is a polarization between Hindus and Muslims that has a negative impact on national politics. Whether this polarization of Muslims will work as an electoral strategy will be the critical question.

In a Pew survey of almost 30,000 Indian adults conducted between late 2019 and early 2020, nearly two-thirds of Hindus say being Hindu is essential to being genuinely Indian. The BJP draws its power from Hindu voters who see being Indian as having a solid relationship and speaking Hindi. In contrast, only 33% of Hindu voters value these aspects of national identity.

It’s a popular idea among BJP rhetoric that Hindus are treated as minorities in their own country. In a city where the legacy of partition still looms large, there are all these dog whistles based on a sense of Hindu victimhood, Vaishnav says. According to him, these slogans have resonance because there has been religious violence and riots in the past.

The economic performance of the BJP has also become a hot topic.

According to economists, there is a crisis due to rising prices, increasing unemployment, and rising inflation. According to Al Jazeera English, the unemployment rate jumped from around 7% in November and below 5% in 2017 to almost 8% in December.

According to Al Jazeera English, nearly thirty million Indians aged 20 to 29 constitute the majority of those unemployed, as reported by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. Sircar says the unemployment and jobs crisis has affected much youth who have been associated with the BJP and Modi. It will be a significant change if discontent around the economy disrupts voting patterns associated with Hindu-Muslim polarization in Uttar Pradesh since elections there have “not been fought on economic grounds for a very long time.”

In addition, the ruling party has been concerned about widespread opposition to agricultural reforms that have been criticized for favouring big agribusiness over smaller producers. Farmers in western Uttar Pradesh also mobilized against the laws despite most protests occurring in Punjab and Delhi. After a year of protest, Modi repealed the measures in November, but it is unclear whether this will be enough to restore goodwill among these farmers, who are still calling for increased support for their products.

A devastating COVID-19 wave swept through last spring in this election. A mass grave was found in Uttar Pradesh, and oxygen and hospital beds were in short supply. Rather than targeting state and national officials, analysts suggest most of the discontent may be directed at district officials.

According to Sircar, the effects of the farmers’ protest and the pandemic may be limited indirect political impact. The farmer protests or the pandemic do not determine whether or not he will vote for a particular party, he says.

Modi’s results: what do they mean?

BJP’s objective would be to make 2024 seem inevitable with a victory in Uttar Pradesh, says Vaishnav, while causing turmoil among opposition parties, which may shuffle their leadership. Akhilesh Yadav’s popularity will be mainly tested in Uttar Pradesh.

Despite an opposition victory in Uttar Pradesh, Jyoti warns that Modi’s appeal isn’t guaranteed to be undermined significantly by it in 2024. Despite poor performance in Indian state elections, the BJP often performs well in those same areas for national elections.

The BJP might consider reevaluating its strategy and whether Yogi Adityanath is the right candidate for chief minister if it loses, though it is unlikely. Sircar says that if Uttar Pradesh falls due to its long history of Hindu Muslim polarization, there will be serious questions about the BJP’s ability to turn it around. Modi’s position can likely remain secure regardless of what happens. Vaishnav says, “there is no one who can stand up to Modi at the national level.”

However, that’s not always the case; things may change as India needs a better and more educated government.

Edited and published by Ashlyn Joy