Will your state government be able to provide a vaccine for your safety now?

The National Vaccine Administration Expert Group (NEGVAC) was formed for the first time on 20 August last year. The Commission declared that all procurements would be carried out centrally, and also gave a very specific directive to countries requesting that they not determine different procurement paths. Since then, the NEGVAC has convened 23 times, without ever discussing any amendments to this Central Procurement Order. However, the Center reversed this decision at a meeting chaired this week by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and now permitted both the private sector and states to purchase vaccines directly. This means that our Covid-19 vaccination policy can now move from a closely regulated procurement and delivery model to a décentralized model where the quantity, price and vaccine provider will be determined for each state, each hospital chain and each pharmacy. In several cases, this drive towards decentralized procurement is an important improvement step, albeit it is a little late. After all, every state has a different population profile, prevalence of diseases and capacity for the health system. However, the ensuing dash to procure vaccines in the midst of a pandemic needs to be seen such as given all the complexities, what could be the inventory holding of each state? Does each state have sufficient capacity to identify which viral variants are the most common and then assess which vaccine will be the most appropriate?

States in Competition

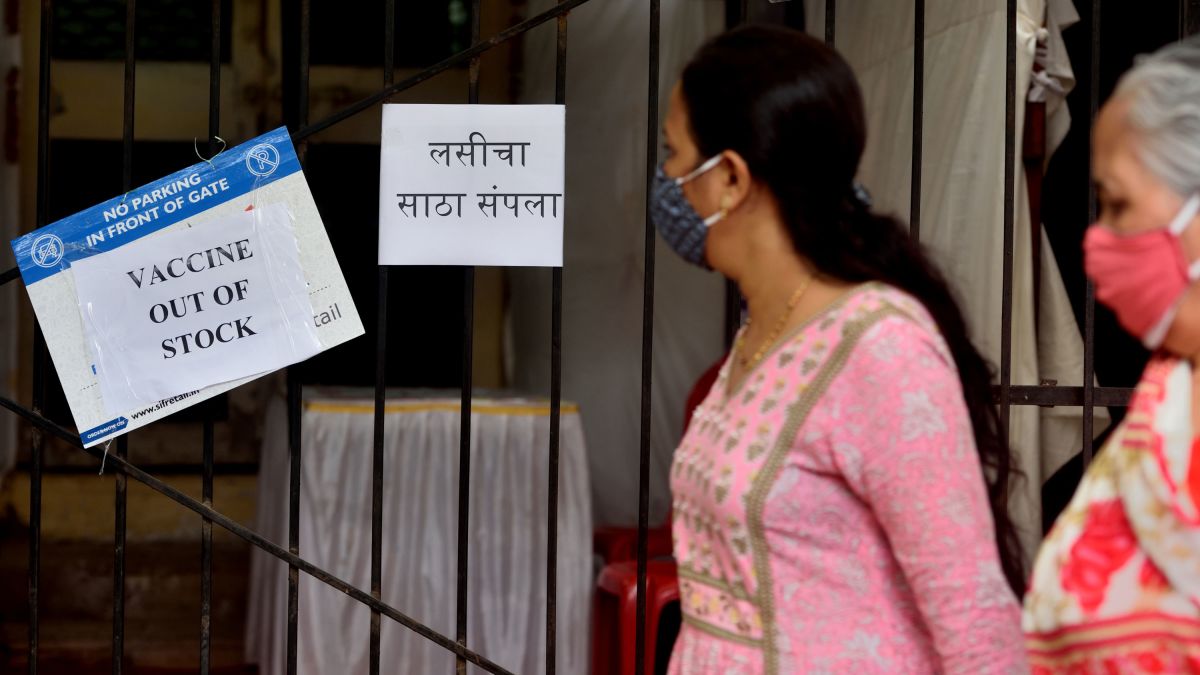

We’re in the middle of a second wave that just hit the country and seems to be more disastrous than the previous one. There have been many new virulent strains of the virus, but the government has dragged its heels on population vaccination. The ramifications are now imported with the transition to a decentralized model. In the early stages of the pandemic, a similar crisis was created in the United States, where a severe shortage of PPE and ventilators led to extreme rivalry between states trying to outbid each other to obtain essential resources. If anything like this happens in India in the coming months with regard to the acquisition of vaccines, the result will be extremely unfair, as big and rich states such as Maharashtra profit, while smaller states with less funding will lose out.

It has been shown that 60% of combined doses were taken from 12 April in only eight states, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Kerala—even during the ongoing vaccination process. At least six states are in acute trouble, as they now account for more than 50% of the daily load of infections. There will be no space for rough negotiations between these states. They would pay a premium price than the states who can wait a little longer to deal harder. Will the troubled areas then tend to stock up and buy something that the economy offers? Will this not just lead to weaker states being supplied less?

There have been several instances of drug and vaccine manufacturers imposing strict pre-conditions when states have negotiated directly, especially when stocks are in short supply. This puts a lot of pressure on smaller states, which typically have a weaker drug-handling infrastructure. State-level procurement processes are incredibly complex. The much-heralded Tamil Nadu model of a fully centralized pooled procurement process is based on a complex network of factories, transportation services, and an IT-based inventory tracking scheme. Kerala does so on a much larger scale. Both of these southern states have invested large sums of money to improve their healthcare infrastructure. Maharashtra also has a decentralized distribution system in place, which purchases almost 2,000 medicines in the open market. Buying directly would not be a challenge for these three states, unlike many others who have little financial and human resources.

Moreover, large-scale vaccine wastage will be a major concern in the coming months. Resource storage would be unreliable, and demand forecasts would be weak. In several of India’s states, this is the reality. There is also the acute problem of overdue payments, harassment of bills and corruption accusations all around. Such transaction costs will only boost the unit price of vaccinations in some states at the state level. For this, there is precedence. One best case in point is how different areas purchase medical equipment within the framework of the National Health Missions (NHM). The device manufacturers will handle various different states differently, depending on size, historical connections, accessible health facilities, reimbursement assurances, corruption levels and compensation arrangements. For example, it is inevitable that the Maharashtra government will wield tremendous power over Serum Institute in the coming months, just as the Telangana government will wield power over Bharat Biotech. In many ways, these state governments would have the first right of refusal.

Vaccination race

Will the fact that different states purchase different vaccines lead to confusion among citizens? In the midst of the country’s already severe vaccine hesitancy, this plethora of suppliers will result in a new influx of WhatsApp messages and rumours about people suffering side effects. We’ve had enough scepticism for only two vaccine labels.

With vaccine apprehension playing a large role in low vaccination rates, the most ambitious estimates suggest that by December 2021, India will have vaccinated 40-50 per cent of its population. Covid-19 vaccination coverage varies by state. By May 2022, India will be able to vaccinate 60 per cent of its population at the current estimated rate of about 3.5 million doses per day, ensuring that the rate of vaccines remained constant. Three-fifths of the population would be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity, which will take about 1,450 million doses.

What choices do the states have now that this current system is in place? Does a state chief minister have a political option? The Uttar Pradesh chief minister, Yogi Adityanath, was the first to speak out, pledging free vaccines to everyone above the age of 18 in his province. Recently, the Prime Minister himself promised the same to everyone in Bihar. Each government will also be required to follow suit. Alternatively, you risk losing the next election. As a result, each state will be dedicated to free compulsory vaccination in one way or another. The issue would be the capacity to produce and the difficulty of persuading sceptics to take the vaccine.