Why Credit Default Swaps Are the Culprit Behind Europe’s Banking Turmoil?

There are markets, such as the single-name CDS market, that are highly opaque, immensely shallow, and extremely illiquid. Even with just a few million (euros), the concern spreads to the banks, which have trillions of euros' worth of assets and affects both stock prices and withdrawals of deposits.

Why Credit Default Swaps Are the Culprit Behind Europe’s Banking Turmoil?

Credit default swaps have come under scrutiny due to the turbulence in Europe’s banks that followed the collapse of 167-year-old Credit Suisse and runs on local banks in the U.S.

Investors have severely discounted the shares and bonds of several of Europe’s most recognizable banks, including Deutsche Bank, Germany’s largest lender, out of concern over which bank would be the next to fail.

The actions came after a spike in the price of credit default swaps (CDS), which are used to insure against default on debt held by Deutsche Bank, to a more than four-year high last week.

The volatility of Deutsche Bank’s instruments, particularly CDS, was cited by Andrea Enria, the head of banking supervision at the European Central Bank, as a concerning indication of how readily investors could be alarmed.

There are markets, such as the single-name CDS market, that are highly opaque, immensely shallow, and extremely illiquid. Even with just a few million (euros), the concern spreads to the banks, which have trillions of euros’ worth of assets and affects both stock prices and withdrawals of deposits.

WHAT EXACTLY ARE CDS?

Credit default swaps are derivatives that protect from the possibility that a bond issuer—such as a business, a bank, or a sovereign government—will fail to pay its creditors.

Bondholders anticipate receiving interest and their original investment back when the bond matures. They must take the risk of holding that debt because they have no assurance that one of these things will occur.

By offering some sort of insurance, CDS assists in reducing the risk. The International Swaps and Derivatives Association estimates the CDS market to be worth $3.8 trillion. Yet, according to ISDA data, the market remains much below the $33 trillion it reached during its peak in 2008.

In comparison to the equity, foreign currency, or global bond markets, where there are more than $120 trillion in outstanding bonds, the CDS market is modest. According to the Bank for International Settlements figures, the average daily volume of foreign exchange is close to $8 trillion.

These derivatives can have sporadic trading. According to data from the Depositary Trust & Clearing Corporation, even for large corporations, the average daily number of CDS trades can occasionally be in the single digits (DTCC).

Due to this, it is difficult to manage the market, and even a little CDS trade can result in a significant price change.

How do Credit Default Swaps operate?

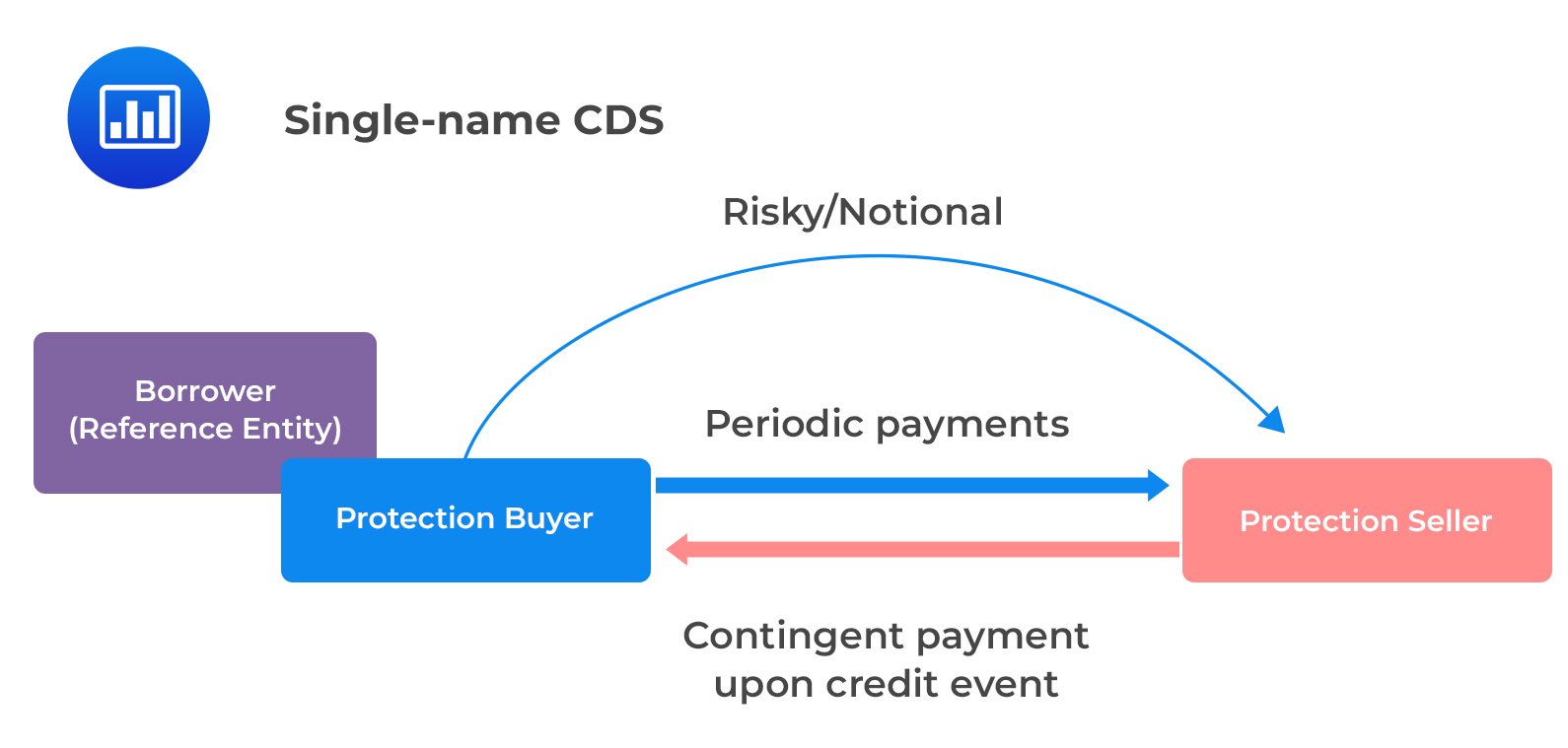

A derivative transaction known as a credit default swap transfers the credit exposure of fixed-income instruments. Bonds or other types of securitized debt, which are derivatives of loans sold to investors, may be involved.

Consider the scenario when a business sells a bond to a buyer with a $100 face value and a ten-year maturity. The company can agree to make the $100 repayment after ten years, along with ongoing interest payments.

As the issuer of the debt cannot ensure that it will have the funds to pay the premium, the burden of that risk falls on the investor. A debt purchaser may purchase a credit default swap (CDS) to hedge against the risk of a loss in the event of a default by the debt issuer.

Debt instruments sometimes have longer maturities, which makes it more difficult for investors to calculate the risk of an investment. A mortgage, for example, can have a 30-year term. It is impossible to predict whether the borrower will be able to make payments for that length of time.

These contracts are, therefore, a well-liked method of risk management. Up until the contract’s maturity date, the CDS buyer makes payments to the CDS seller. In exchange, the CDS seller promises that in the case of a credit event, it will reimburse the CDS buyer for the value of the security as well as all interest payments due between that point and the maturity date.

WHO PURCHASES CDS?

Through an intermediary, frequently an investment bank, investors in bonds issued by corporations, banks, or governments can purchase CDS insurance. The investment bank locates a financial institution to issue an insurance policy on the bonds. These transactions are “over-the-counter,” meaning they bypass a central clearing house.

The counterparty will get a regular fee from the buyer of the CDS and will thereafter assume the risk. In exchange, much like an insurance payout, the seller of the CDS pays out a specific sum if something goes wrong.

Credit spreads, which represent the number of basis points that the derivative’s seller costs the buyer in exchange for offering protection, are used to quote CDS. The spread widens in proportion to the estimated risk of a credit event. For every $100 in bonds that the owner of a CDS quoted at 100 basis points holds, insurance will cost them $1.

WHAT COULD CAUSE CDS?

A “credit event,” such as the bankruptcy of a debt issuer or the non-payment of bonds, might cause a CDS payout to occur.

To allay investor worries that CDS would not cover actions made by governments to aid distressed companies, especially banks, a new category of credit event known as “Governmental Intervention” was launched in 2014.

CDSs are actively traded, just like any other financial asset. Demand for a debt issuer’s CDS rises as risk perception around it does, increasing the gap.

The government sector is the largest market for CDS. According to DTCC data, Brazil leads the list with $350 million in daily notional average trades.

According to DTCC data, Credit Suisse’s CDSs saw the greatest activity on the corporate front in the final quarter of 2022, with $100 million exchanged daily.

KEY ROLE IN THE CRISIS OF 2008

One of the financial products at the heart of the 2008 financial crisis was CDSs. Among the many banks that provided CDS to investors on derivative products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which are mortgages combined into one package, were Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers.

A wave of mortgage defaults resulted from the steep increase in U.S. interest rates that occurred during 2007, making MBS and other bundled securities worthless to the tune of billions of dollars. Lehman and Bear Stearns, among other institutions, received substantial CDS payouts.

A REPEAT OF 2008?

No. Since that time, a lot has changed. During that time, various derivatives, including CDS, were much more frequently employed and covered a more comprehensive range of assets, many of which experienced losses.

The current turbulence does not correspond to a significant decline in the value of the underlying securities for the CDS. Rather than actual risk, it is more about perceived risk.

As investors worried about the soundness of the more extensive European banking system, CDS on Deutsche Bank’s five-year debt increased to above 200 bps last week from 85 bps just two weeks prior.

According to Enria of the ECB, the central clearing of CDS would increase transparency while lowering the risk of volatility. He argued that it would already be a significant advancement if these markets were centrally cleared instead of using OTC, secretive transactions.

Investors purchase credit default swaps to lessen the risk of underlying asset defaults. They were heavily utilized in the past to lower the risks associated with investments in mortgage-backed securities and fixed-income products, which aided in the development of the 2007–2008 Financial Crisis and the crisis of sovereign debt in Europe.

Investors continue to utilize them, but because of laws passed in 2010, trading has considerably decreased. In the first quarter of 2022, the global derivatives market transacted more than $200 trillion in derivatives, with credit default swaps accounting for around $3 trillion, or 1.9%, of that total.

Edited by Prakriti Arora