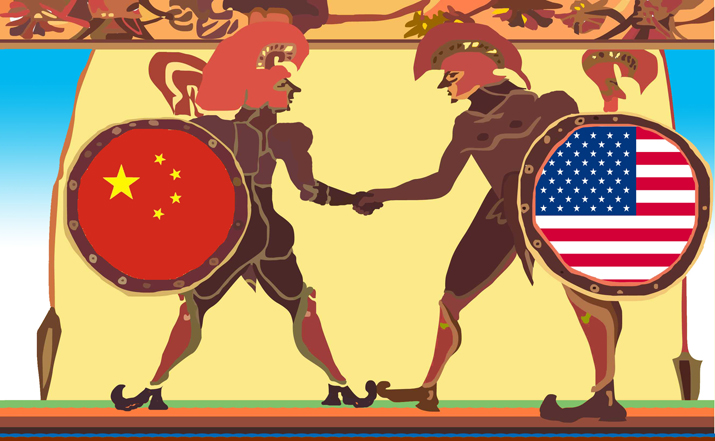

The Thucydides Trap : The United States and China

What is Thucydides Trap?

In “History of the Peloponnesian War”, Thucydides, the Athenian historian of the ancient times, did something that no one had ever done before: tell the story of a conflict without divine or magical interventions, solely based on the motivations of the protagonists. The central idea of the work is that “it was the rise of Athens and the fear that inspired Sparta that made the war inevitable.” The confrontation between an established power and another one in its ascent as the origin of war is what is called “the Thucydides Trap”.

In “Destined for War. Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?” Harvard professor Graham Allison wonders if the US and China are doomed to go to war or if there is hope that they will stop sooner.

The first thing you need to know is that a rising power can be described with a very traditional term: “baseball player.” Before criticising China’s actions on its path to hegemony, it is necessary to remember how intractable the United States was at the beginning of the 20th century. Allison remembers what was the foreign policy of the most imperialist President of all, Theodore Roosevelt: it provoked the Spanish-American war to eliminate the presence of a European power on the nearby coasts of Cuba and, already put, he stayed with Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.

He forced Britain, Germany, and Italy to settle their differences with Venezuela through arbitration rather than with gunboats, letting them know in passing that they were no longer welcome in the Western Hemisphere; fostered the independence of Panama, because he was determined to build a canal there and Colombia, the legitimate owner of the territory, did not see it clearly; imposed on Canada a completely biased arbitration for the delimitation of its border with Alaska, which the Canadian press openly and rightly called “theft”; American troops intervened in the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Cuba to defend the economic interests of American businessmen; William Taft, blatantly intervened in Mexican politics.

Roosevelt’s example may be extreme, but in principle, every rising power is called to step on a few calluses – either on purpose or unintentionally – simply because it calls into question the status quo that had come so well to the hitherto hegemonic power.

Allison highlights how China differs from the United States. Traditionally, China has seen itself as the Middle Empire, the land that mediates between heaven and earth and to which its neighbours pay homage, offer tribute and whose civilisation they admire and try to emulate. Her vision of the international scene was hierarchical: all other kingdoms had to recognise China’s superiority, a superiority that was expressed in civilising and ethical terms. The 150 years from the decline of the Qing Dynasty to China’s reappearance on the international scene have been a time of collective humiliation. The message from today’s Chinese leadership, which resonates with the entire population, is: “never again”.

To describe the Chinese world view, Allison turns to Huntington and his clash of civilisations, a book with more mistakes than hits. According to Huntington, Confucianism reinforces “the values of authority, hierarchy, the subordination of individual rights and interests, the importance of consensus, the avoidance of confrontation, ‘saving face’, and, in general, the supremacy of the State over society and society on the individual. ” It is true that many of these traits can be applied to China, but to attribute them to Confucianism is too simplistic. On the other hand, this reading is left out to the “legistas”, a group of thinkers who were like Machiavelli.

The West understands international relations as an order of States that are sovereign and equal. We all know that equality is more an aspiration than a reality, but we pretend that we don’t realise it. The Chinese vision is one of the hierarchical and harmonious relations, in which China occupies the top of the pyramid.

But the fundamental difference between China and the United States has to do with time and history. China prides itself on an uninterrupted history spanning five millennia. That gives them an idea of permanence (China has always been there) and a very long-term view of events, allowing them to distinguish the urgent from the important. Thus, for example, in the 1980s Deng Xiaoping chose to freeze the controversy with Japan over the Senkaku / Diaoyu islands for a generation because it simply was not the time. What western politician would have been capable of something similar?

Faced with this vision that measures things in terms of millennia, the United States, which has not yet completed 250 years, is seen as the result of a historical experiment, as a new beginning, not as the result of an immemorial historical process. The United States pays little attention to history and each challenge seems new and unprecedented. Its politicians are increasingly attentive to the newscast cycle and confuse strategy with bullet-points full of colourful and, if possible, alliterative statements.

At the geostrategic level, China is the country of realpolitik. It is the logic of power and the concrete situation that marks their actions. International law, religious or ideological considerations, do not enter their calculations. Their world view is holistic: everything is connected to everything. They prefer a policy of small gradual steps, which improve their position almost imperceptibly.

To understand his way of conducting geostrategy, compared to the West: our traditional strategic game is chess, where using brute force one tries to take control of the centre of the board; whereas they have the weiqi. The goal in weiqi is to surround the opponent. It requires long-term planning and gradually improving one’s position. In weiqi, there are no such blows in which one surprise eats the queen of the other and turns the game around.

Another simile to understand the differences between China and the US at the geostrategic and military level is to look at its main strategic thinkers: von Clausewitz for the West and Sun Tzu for China. Von Clausewitz privileges the key battle in which one annihilates the forces of the adversary; Sun Tzu prefers stratagems and his ultimate goal is to bring about the demoralisation of the opponent so that he surrenders without having to defeat him on the battlefield.

The Thucydides Trap that US and China find itself in, with the world as the witness, will require more time with the unfolding circumstances to ascertain who will stay on the top.