Pandemic And Nature: To What Extent Are Humans Responsible For The Spread Of Pandemics?

The increase in outbreaks is due to an increasing tendency of more individuals to congregate in urban areas. She also emphasises that the yearly loss of millions of acres of natural habitat contributes to this rise. This is especially relevant since around three-quarters of new infectious illnesses begin in animals and then spread from species to species until they may infect humans under specific situations.

According to the adage, “prevention is better than cure.” Nothing better exhibits this concept than “Disease X.” It’s been just a year since the economy was back on track as the world coped with the deadly pandemic; it seems we are sitting on the blanket of another one! Yes, you read that right. Global health experts have warned that COVID-19 might be a starting point for a more devastating Disease X Pandemic. Dame Kate Bingham, the head of the UK’s Vaccine Taskforce, expressed appreciation that COVID-19 was not more lethal and warned that the next pandemic might kill at least 50 million people.

As COVID-19 becomes a more regular and recurring health condition, UK doctors are preparing for a new pandemic known as “Disease X.” They warn that the impacts of this new virus may be equivalent to those of the 1918-1920 Spanish Flu. They warn us that the next pandemic might kill 20 times as many people as the coronavirus did. More than 2.5 million people died worldwide since the COVID-19 outbreak began in 2020. The World Health Organization has dubbed this “Disease X Pandemic,” to combat it, vaccines will need to be produced and distributed on time again. However, there is no guarantee that this will happen.

Some public health experts anticipate the next Disease X will be zoonotic, which means it will begin in wild or domestic animals before spreading to people. So far, the lethal Ebola, HIV/AIDS, and COVID-19 pandemics have all been zoonotic. Similarly, while new zoonotic infections must be studied, the prospect of an engineered pandemic pathogen cannot be overlooked. The emergence of such viruses, whether by laboratory accident or as an act of bioterrorism, may also result in a terrible Disease X, which has been identified as a global catastrophic danger.

According to Bingham, the increase in outbreaks is due to an increasing tendency of more individuals to congregate in urban areas. She also emphasises that the yearly loss of millions of acres of natural habitat contributes to this rise. This is especially relevant since around three-quarters of new infectious illnesses begin in animals and then spread from species to species until they may infect humans under specific situations.

But how the migration of people from rural to urban provinces is responsible for the pandemic?

Every day, the globe becomes increasingly urban, and this trend has been continuous since the 18th-century Industrial Revolution. The quick influx of people is not universal, and industrialised nations are already urban. Still, Asia and Africa are predicted to have the greatest increase in urban population over the next 25 years. Urbanisation presents several problems to global health and infectious disease epidemiology. New megacities can act as incubators for recent outbreaks, and zoonotic diseases can spread quickly and become global dangers.

Chronic diseases are becoming increasingly important in developing countries. In 2011, the significant causes of mortality worldwide were ischemic heart disease, stroke, lower respiratory infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diarrhoeal disorders. However, infectious illnesses continue to have a significant impact in low-income nations. In these situations, the top three causes of mortality are all infectious illnesses: lower respiratory infections, HIV/AIDS, and diarrhoeal disorders. Many low-income nations will likely see significant expansion in their urban populations, posing significant difficulties for governments and health care to stay up with and enhance their social services and health care as these regions grow.

Poor Sanitation.

The growth of new contemporary cities introduces new hazards and problems in the form of developing infectious illnesses. Poor housing, for example, can contribute to developing insect and rodent vector illnesses and geohelminthiases in the urban environment. This is due to insufficient water supply, poor sanitation and waste management. This creates a conducive environment for rodents and insects transporting diseases and soil-transmitted helminth illnesses.

One of the examples where poor sanitation has caused a trigger for outbreaks is the ‘Slum in Mumbai during the COVID outbreak’. Nearly 5.5 million people live in awful circumstances in Mumbai’s slums and are mainly denied access to some of the most basic services, such as safe and clean bathrooms and water. Since 2011, numerous major pockets of slums in the eastern suburbs’ Ghatkopar-Kurla-Govandi-Mankhurd belt and the western suburbs’ Dindoshi region in Malad have increased in size and population density, surpassing Dharavi. With further migration and slum spatial growth, this ratio will only deteriorate in the future.

While Mumbai’s slums have now been recognised as the city’s largest COVID-19 clusters, overused and poorly maintained enormous communal toilets within these slum pockets were considered the “major reason” for the city’s COVID-19 outbreak. Due to the lack of separate toilets in each slum home, these decaying mega-sized community toilets have become the sole sanitary facilities available to millions of slum dwellers. At those times when adhering to social distance standards in densely populated slums was difficult enough, it was practically impossible for individuals to avoid intimate contact with each other in the multi-story community toilet facilities that they must use regularly.

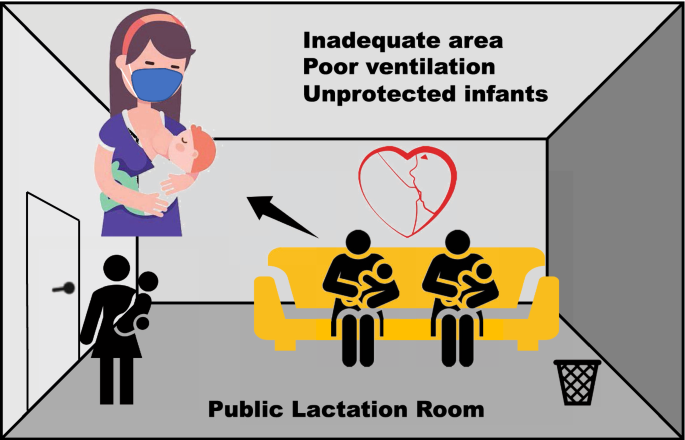

Poor Ventilation.

Respiratory tract infections can be obtained if buildings lack efficient fuel and ventilation systems.

Examples are there to demonstrate how poor ventilation can be a contributor to outbreaks. The 2003 worldwide SARS epidemic, the growing potential threat of bio-terror attacks through deliberately releasing agents like anthrax or smallpox, the H1N1 influenza epidemic in 2011, and MERS in 2013 have all highlighted the potentially serious threat of airborne infection in buildings to human health. Growing urbanisation, deteriorating overcrowding in modern megacities, and quickly expanding global transportation networks may hasten the transmission of airborne infectious illnesses. Most airborne transmission happens in interior situations, where most individuals spend more than 90% of their time.

Since the SARS epidemic, the function of ventilation in limiting airborne illnesses has received much attention. Previous research has thoroughly investigated the dispersion process of airborne droplets/droplet nuclei in space, the risk calculation of airborne infection, the function of airflow rate, the influence of airflow patterns, and so on. Many researchers and studies believe that this virus may also be transmitted through the air and survive for up to three hours in the air. This raises the question of whether enough is being done in terms of ventilation to limit the possibility of the spread of this or other airborne infections.

Consumptions of contaminated eatables and fluids.

Due to microbial toxins and zoonoses, contaminated water can transmit disease, as can improper food storage and preparation. The recent example of the Nipah outbreak in Kerala can be the best example of how contaminated food and storage can catalyse virus outbreaks. Though the investigation is still ongoing, there has been a hypothesis that the virus could have been spread by consuming the fermented date palm syrup contaminated by bat urine and saliva.

How loss of natural habitats can be a catalyst for outbreaks?

Evidence reveals that emerging infectious illnesses, such as COVID-19, start in animal species and that land-use change is an essential channel for pathogen transmission to people, according to a paper released in April 2021. Land conversion and habitat fragmentation, for example, increase the likelihood of animal-human contact and, as a result, disease transmission. Research indicates that “deforestation resulting in crop monocultures is particularly problematic for elevating infection risks in susceptible nearby populations”. All these consequences of animal habitat loss and fragmentation enhance contact between wildlife and humans, increasing the likelihood of zoonotic disease spillover.

The illicit wildlife trade, a multibillion-dollar industry, has worsened significantly during the last decade. The trade has gotten more organised, but authorities have not intervened sufficiently. Following the global breakout of COVID-19 in March, the Chinese authorities imposed a permanent ban on the trade and eating of wild animals. Wildlife markets, however, are not the main source of zoonotic infections. Humans are contributing to the spread of illness by continuing to change natural habitats and infringe on them for hunting and gathering.

Another notable example is the incredibly lethal Ebola hemorrhagic fever, which first appeared in West Africa in 1976 and has since caused multiple outbreaks with fatality rates of up to 43%. A study of 40 Ebola outbreaks that occurred after 2004 discovered that they were strongly associated with the recent destruction of mature forests and natural habitats, which resulted in more frequent interaction between humans and sick animals.

Another is the Marburg virus. Both the Marburg and Ebola viruses are Filoviridae (filovirus) members. Despite the fact that they are spreaded by distinct viruses, the two illnesses are clinically identical. Both diseases are uncommon and have the potential to generate large-scale outbreaks with substantial death rates.

Fruit bats have drawn attention as a natural reservoir for the Nipah virus when it came out in Kozhikode, Kerala. This implies that the virus may persist in the bat’s body without producing sickness, allowing it to spread to vulnerable animals such as people or pigs when bats come into touch with them. As agriculture and urbanisation destroy bat habitats, bringing them into human residences, such interaction is becoming more common.

Furthermore, rapid industrialisation and population growth have resulted in the degradation of forests all over the world. Fruit bats experienced constant hunger when their native home was lost, causing psychological stress in these creatures. Hunger and stress caused Nipah viruses to multiply quickly within fruit bats’ bodies; hence the transfer of the virus to humans is again faster.

Another possible outbreak, the Lassa fever, is a severe viral hemorrhagic fever resulted by a zoonotic virus that spreads to people from rat reservoirs on a regular basis. It is still unknown how climate and land use changes may influence the virus’s endemic range, which is now restricted to portions of West Africa.

Experts demonstrate how temperature, precipitation, and the existence of pastures impact ecological appropriateness for viral circulation by investigating the environmental variables related to virus occurrence using ecological niche modelling. They discovered that regions in Central and East Africa will likely become suitable for Lassa virus circulation over the next decades based on projections of climate, land use, and population changes, and they estimate that the total population living in ecological conditions suitable for Lassa virus circulation may drastically increase by 2070.

Is this the first warning of this new pandemic?

May 2023– The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 no longer a global emergency on May 5, 2023, putting a stop to the pandemic that killed at least 7 million people globally. Only days later, experts are concerned that a new ‘Disease X’ may unleash an even deadlier pandemic.

June 2022– British health experts allegedly urged the UK government to be prepared for ‘Disease X’ following reports of poliovirus detection in sewage samples in London, monkeypox, Lassa fever, and avian flu in recent years.

2017– The WHO originally issued a list of diseases in 2017 that potentially create a “deadly pandemic” and then undertook a prioritising exercise the following year. Currently, the list includes the following.

- COVID-19.

- Marburg virus disease and Ebola virus disease.

- Lassa fever.

- MERS and SARS.

- Nipah.

- Zika.

- The latest entry to the list is “Disease X.”

What efforts can be taken to deal with these future outbreaks?

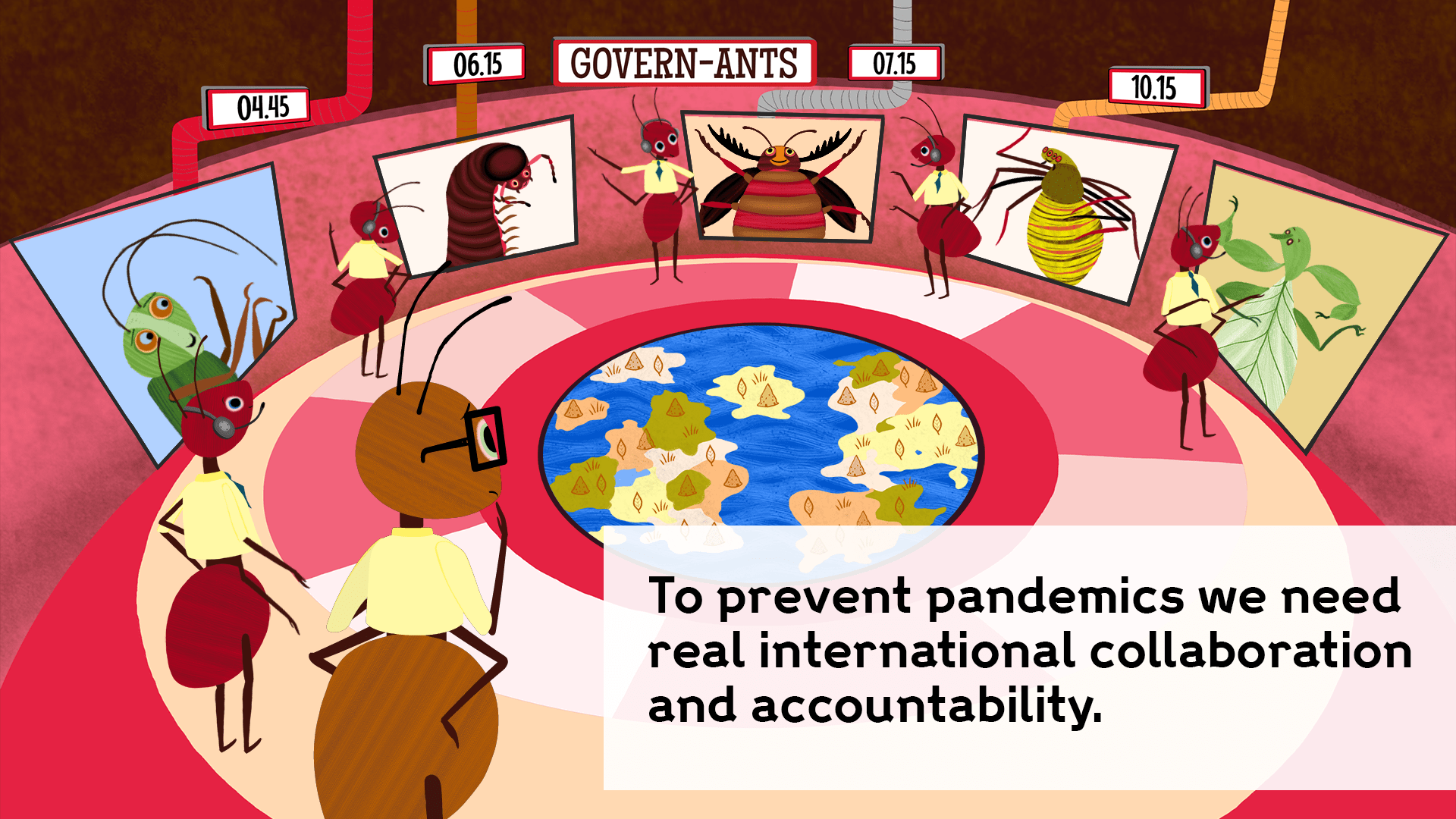

Pandemic planning and response are classic examples of “global public goods”: until the new virus is managed everywhere, the risk of pandemic revival persists. One of the first steps, according to Bingham, is to assign the appropriate financial resources, basically placing “the money on the table.” As stated by Bingham, the monetary penalty of inactivity is seismic. After all, even COVID-19, a weaker virus than Disease X, managed to cost us $16 trillion in lost production and public health spending.

Despite increasing mobilisation during the Ebola outbreak in 2014-2016, funding for pandemic planning and response has been insufficient. Given the “global public good” character of such investment, it is in the interests of governments to spend more and better on pandemic preparation in other countries. Setting up mechanisms to track such flows can greatly improve efficiency. Global mobilisation to combat the health effects of COVID-19 has been tremendous, but more has to be done. The function of development cooperation in limiting disease transmission in poor and middle-income nations is critical. In addition to obtaining additional funds, it can concentrate on developing and disseminating knowledge of solutions, as well as promoting best practices in response.

For the first time, governments throughout the world recognise the need for pandemic preparedness. While the G7 and G20 may have reached wide agreement on some of the actions required to avert – or at least minimise – the next pandemic, one of the most critical concerns remains unanswered: how will we pay for it? Is there a rational and painless approach to accomplish pandemic readiness, given the economic ramifications of the Ukraine war and with many nations still hurting from the fiscal effect of COVID-19?

Innovative financing, development financing, and preparing better economic packages are some of the measures that can be taken by the authorities that can help the nation deal with these terrible outbreaks.

Conclusion.

Large intensive livestock farms can cause “spillover infections” from animals to humans, and increased transportation of animals and animal products has also added to the threat of new illnesses. Every year, new strains of avian influenza spread in wild birds across the world. Intensive poultry farming practices enhance the likelihood of wild bird infection of domestic birds and consequent transfer to poultry workers.

Encroachment into virgin forests for mining and lumber production can potentially expose humans to pandemic infections such as Ebola. Other sources include disease amplification in healthcare settings at the start of a pandemic when infection prevention and control measures are insufficient, increased spread in densely populated cities, and inadequate biosecurity measures in laboratories conducting research on high-risk pathogens, which results in accidental release. The growth of technology and information on bioweapon development raises the possibility of the purposeful release of a biological agent as another feasible scenario. And the list doesn’t end here; there are many to add on.

The Coronavirus pandemic will not be the last in our lifetime. Scientists warn that the threat presented by zoonoses (infectious illnesses that spread from animals to people) is growing. And the threat of a new pandemic is greater than ever. So as the article started, ‘preparation is better than cure’ is the only possible way to save the human race from the possible future pandemics!