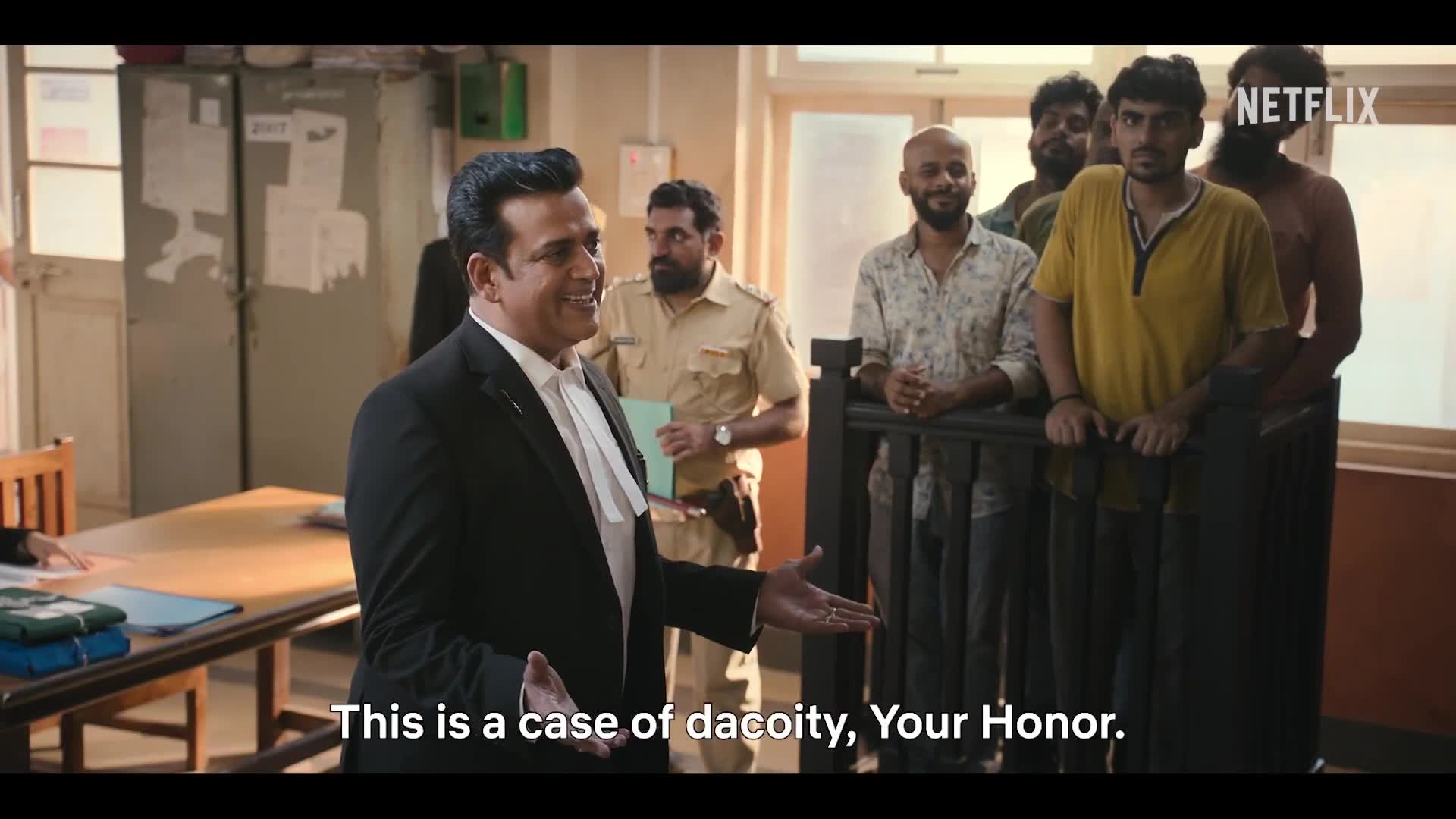

Maamla Legal Hai- How A Netflix Show Displayed The Brutal Reality Of Indian Legal Landscape And Broken Machinery Of Indian Judiciary!

Justice Delayed Is Justice Denied: How Netflix's "Maamla Legal Hai" Accidentally Became The Most Honest Legal Documentary

Remember when we were kids and played “court-court”? One would be the judge wearing a black towel as a robe, another the stern prosecutor pointing dramatically, while the defendant would cry theatrically before being sentenced to the terrible punishment of standing in the corner. Little did we know that our childish game captured the essence of the Indian legal system far better than any textbook ever could – theatrical, arbitrary, and ultimately resolving very little. Netflix’s “Maamla Legal Hai” has now done what countless legal reform commissions have failed to do: showcase the absurdity of our judicial system in a way that’s simultaneously hilarious and heartbreaking.

The show, while marketed as comedy-drama, should frankly be reclassified as a documentary. When young advocate Ananya Shroff enters the profession with starry-eyed idealism only to be met with a stipend that wouldn’t cover a month’s worth of court commutes, it isn’t creative storytelling – it’s Tuesday for most junior lawyers across India. According to a deeply depressing 2020 survey spanning seven High Courts, over 79% of lawyers with less than two years at the Bar earn less than ₹10,000 monthly.

That’s right, folks. The people entrusted with upholding our constitutional rights are earning less than what many pay for their monthly Netflix, Amazon Prime, and food delivery subscriptions combined. In 2024, the Bar Council of India recommended a minimum stipend of ₹20,000 for junior advocates in urban areas and ₹15,000 in rural regions, which sounds magnificent until you realize it’s about as enforceable as a pinky promise in kindergarten.

In one particular scene, interns are paid ₹6,000/month plus a samosa – the samosa presumably being the nutritional support needed to carry the multiple kilograms of case files they lug around daily. And then we wonder why brilliant law graduates from prestigious National Law Universities abandon litigation faster than passengers jumping from a sinking ship. When the Chief Justice of India publicly questions this exodus, one wonders if His Lordship has ever tried living in Delhi or Mumbai on what amounts to loose change found between couch cushions. As the Hindi saying goes, “Pet puja, phir kaam duja” (feed the stomach first, then work) – a revolutionary concept that seems to have bypassed the legal profession entirely.

But wait a minute. The financial struggle is just the beginning of this challenging journey. The main source of suffering is the judicial system itself. Recall the first episode where the arrest took place in the wrong section and bail was granted? A clerical error sets a potential criminal free while the victim returns to being vulnerable; a plot twist so common in Indian courts that it barely raises eyebrows anymore. Meanwhile, as portrayed in another Netflix series “Black Warrant,” thousands languish in prison not because they’ve been proven guilty but because they lack the financial means to prove themselves innocent. It’s a legal system where justice is less blind and more means-tested.

The scene where court proceedings are halted because the premises are under siege by monkeys – leading to a strike about how to remove said simian interlopers – may seem like comedic exaggeration until you’ve actually practiced in certain district courts. While lawyers and litigants wait endlessly for their cases to be heard, judges apparently find time for cricket matches in the court premises. One can almost imagine the court circular: “All cases listed for today stand adjourned sine die due to the Honorable Judge’s batting average requiring urgent improvement.” As they say in Hindi, “Jiska koi nahi, uska khuda hai” (God looks after those who have no one) – unfortunately, God seems to have a significant backlog as well.

This isn’t a recent development either. Our legal system’s inefficiency has historic roots deeper than the banyan tree outside every district court. When the British made the present Indian judicial system in the 1860s, they purposefully designed a complicated, procedure-heavy machinery geared toward control rather than justice. The purpose was never efficiency; rather, it was to guarantee that ordinary Indians were so scared by legal proceedings that they would hesitate to challenge colonial power. After independence, we embraced political freedom while holding onto colonial legal frameworks with the zeal of a kid clutching a security blanket. We’ve effectively been running a 21st-century country on a 19th-century operating system, then reacting with surprise when it crashes on a frequent basis.

Remember the character of Advocate Mangal Dheema, who runs a beauty parlor because he knows his law degree alone won’t put food on the table? Again, not fiction. Visit any district court in India and you’ll find lawyers doubling as property dealers, insurance agents, typists, notaries, and yes, even beauty parlor owners. The legal license becomes a side business accessory rather than a professional credential. And Dheema’s cavalier attitude about maybe losing his license? That also holds true in a system where regulatory control varies from uneven to nonexistent. The Advocates Act theoretically provides for discipline, but in practice, it’s enforced with all the vigor of a traffic signal in a power outage.

Meanwhile, Advocate Sujata Negi’s character transformation from idealistic lawyer to pragmatic “liaison” represents perhaps the most honest character arc in legal television. When the system consistently rewards those who know which palms to grease rather than which precedents to cite, is it any wonder that legal knowledge takes a backseat to networking skills? One senior lawyer generally gossips with surprising honesty, “In Indian courts, knowing the judge is frequently more essential than knowing the law.” Justice may be blind, but it does recognize familiar voices.

The show also highlights the huge mismatch between legal education and practice. Students in law schools learn how to construct persuasive arguments using precedent-setting rulings and constitutional concepts. After lunch, these grads proceed into courtrooms where the outcome of a case depends on whether the clerk submitted the papers correctly or whether the judge is feeling upbeat. It is comparable to training Olympic swimmers and then putting them in a molasses-filled pool to compete. It seems like technical prowess is considerably less important than the ability to keep afloat under ludicrous conditions.

This disconnection extends to the infrastructure itself. Our Constitution provides for sophisticated rights and remedies, but try exercising them in courtrooms with non-functional fans, missing chairs, and toilets that would make a medieval dungeon seem hygienically advanced. One particularly authentic moment in the show depicts advocates arguing important constitutional points while battling mosquitoes and power cuts. The message is clear. In theory, justice is required, yet it is insufficient to protect basic comforts.

Another form of legal gatekeeping that is so prevalent that we are unaware of it is the language barrier. The language of court proceedings is English, even though many litigants do not speak it. Imagine the pain you have when you are fighting for your rights in a language you barely understand, through a lawyer you can barely afford, in a system you fundamentally don’t trust! As the character Ananya Shroff gradually realizes, the biggest legal fiction isn’t found in hypothetical scenarios but in the phrase “equal justice under law.”

The show’s portrayal of endless adjournments deserves special mention for its documentary-like accuracy. Cases are postponed because files can’t be located, because the opposing counsel has a “personal difficulty”, or because the judge decided midway through the day that they’ve heard enough matters. There’s an old joke among litigators: “In Indian courts, justice delayed is the norm; justice delivered is the exception.” The Supreme Court’s famous declaration that “justice delayed is justice denied” would be profound if it weren’t coming from an institution where cases from 1994 are still awaiting final hearing.

What makes “Maamla Legal Hai” captivating is how it reflects the unique contradiction of the Indian legal practitioner: tired about the system and sentimentally loyal to its ideals. In private talks, most lawyers recognize the system’s deep failure, yet they will strongly defend it against external criticism. It’s rather like complaining constantly about your eccentric family but being deeply offended when someone else points out their quirks. This peculiar professional Stockholm syndrome perhaps explains why meaningful reform remains elusive despite universal acknowledgment of problems.

The talk also discusses the legal profession’s hierarchical structure, which is another medieval relic that we have remarkably faithfully maintained. While novice advocates find it difficult to cover office rent, senior advocates charge outrageous rates. Judges demand respect that verges on reverence, while criticism of court rulings frequently verges on contempt of court. The entire system operates on an unspoken understanding that seniority trumps merit, connections trump competence, and tradition trumps efficiency. As one character astutely observes, “The law is equal for all” – it’s just that some are considerably more equal than others.

Perhaps the most painful truth “Maamla Legal Hai” exposes is the gap between constitutional promise and judicial reality. “We the People” is how our Constitution opens, and it guarantees equality, justice, liberty, and fraternity. However, the legal system that is supposed to uphold these noble principles functions as though it was created expressly to undermine them. Something basic has failed when common people avoid the courts at all costs, choosing unjust settlements above fair judgment. As the show suggests through its characters’ journeys, our legal system has become less about justice and more about managing disappointment.

For those who’ve never had the dubious pleasure of Indian court proceedings, the show may seem like exaggerated satire. For anybody who has waited for their case number for hours on uncomfortable wooden seats just to be told, “Next date,” it’s a documentary that is almost realistic. The show’s depiction of legal oddities may make us chuckle, but for millions of Indians, these absurdities are not amusement but rather harsh realities that ruin lives and deplete resources.

What makes reform so challenging is that the system’s dysfunction serves powerful interests. Delays benefit those who can afford to wait – typically institutional litigants and the wealthy. Complexity benefits lawyers who can charge for navigating it. Opacity benefits officials who can monetize clarity. The system isn’t broken for everyone – for some, it works exactly as intended. As the saying goes, “Jiski lathi, uski bhains” (whoever has the stick owns the buffalo) – in our legal context, the stick is the ability to endure lengthy proceedings, and the buffalo is justice itself.

None of this is news to those within the system. Law Commission reports dating back decades have diagnosed these exact problems and prescribed similar solutions of more judges, better infrastructure, simplified procedures, enhanced accountability. Yet meaningful change remains inaccessible. Perhaps what “Maamla Legal Hai” achieves through entertainment is what countless reform committees have failed to do through earnest recommendations – making people care about legal dysfunction not as an abstract policy problem but as a human tragedy playing out daily in courtrooms across India.

Humanizing a system that has become nearly mechanically callous to human pain may be the show’s greatest accomplishment. Characters battling the psychological and monetary costs of court proceedings serve as a reminder that there is a person whose life is at stake behind every case number. Every adjournment is the result of another anxious month. Behind every delayed judgment is justice that may arrive too late to matter.

So the next time a Chief Justice wonders aloud why talented law graduates aren’t flocking to litigation, perhaps they should bypass the official reports and spend an evening with “Maamla Legal Hai” instead of “12th Fail’!

Sometimes fiction illuminates truth more effectively than fact – especially when that fiction is barely fictional at all. As for solutions, well, that would require another Netflix series entirely – perhaps titled “Maamla Fix Karo” (Fix the Matter). Until then, as lawyers have been saying for generations while pocketing their meager fees and adjusting their bands, “The law is an ass, but at least it’s our ass.” Small comfort for those trapped in its grinding wheels, waiting for justice that seems perpetually scheduled for the next hearing date.