How did the war between Russia and Ukraine trigger a food crisis?

Russian aggression in Ukraine prevents wheat from leaving the “breadbasket of the world “and raising food prices elsewhere, endangering shortages, starvation, and political instability in underdeveloped nations.

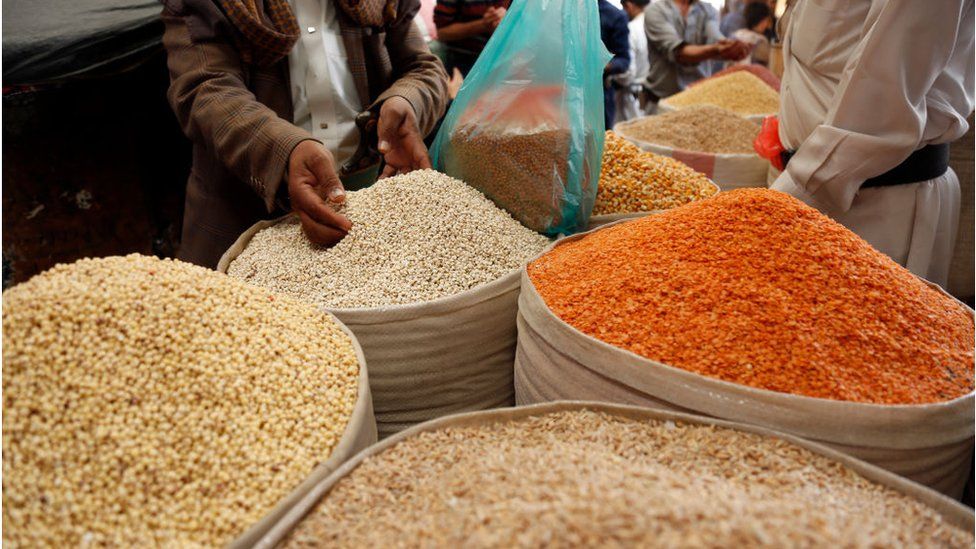

Together, Russia and Ukraine export more than 70% of the world’s sunflower oil, about a third of its wheat and barley, and significant amounts of corn. The world’s largest producer of fertilizer is Russia.

Due to the war, around 20 million tons of Ukrainian grain was unable to reach the Middle East, North Africa, and certain regions of Asia, further driving up global food costs. The urgency is growing as the summer harvest season approaches and after weeks of talks on securing routes to export grain from Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, which have made little headway.

The Kyiv School of Economics’ board member and student of crisis management at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Anna Nagurney, declared that “this needs to happen in the next few months (or) it’s going to be horrible.

She claims that 400 million people rely on the Ukrainian food supply globally. According to the U.N.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, up to 181 million people in 41 countries could do so experience a food crisis or even greater levels of famine this year.

What’s the situation?

Russian blockades of the Black Sea coast have prevented 90 percent of the wheat and other crops from Ukraine’s fields from reaching global markets by sea. The quantity of grain being diverted across Europe through rail, road, and rivers is negligible in comparison to marine routes.

The delays in the cargo are partly a result of Ukraine’s rail gauges not being compatible with those of its western neighbors.

Markian Dmytrasevych, the deputy minister of agriculture of Ukraine, asked EU legislators for assistance in increasing grain exports, including expanding the use of a Romanian port on the Black Sea; constructing more cargo terminals on the Danube River; and reducing red tape for cargo crossing at the Polish border.

To return to the Mediterranean now, you must travel the entire length of Europe. According to Joseph Glauber, a senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute of Washington “has added an incredible amount of cost to Ukrainian grain.

According to Glauber, a former great American economist Department of Agriculture, Ukraine has been able to export approximately 1.From 5 million to 2 million tons of wheat each month since the conflict, more than 6 million tons.

Russian grain is also not leaving the country. Moscow claims that Western sanctions against its banking and shipping sectors prevent Russia from exporting food and fertilizer and are deterring foreign shipping companies from doing so.

To deliver grain to international markets, Russian officials request that sanctions be repealed.However, according to Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, and other Western officials, food is unaffected by sanctions.

What are the sides saying?

In response to Lebanon and Egypt’s refusal to buy its food, Ukraine has accused Russia of bombing agricultural infrastructure, setting fields on fire, stealing grain, and then attempting to sell it to Syria.

Maxar Technologies captured satellite photographs of Russian-flagged ships parked in Syria with their hatches open after loading grain in a Crimean port in late May.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the president of Ukraine, claims that Russia is to blame for the current food crisis. The West concurs, according to authorities like U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and European Council President Charles Michel, who both claim that Russia is turning food into weapons.

According to Russia, shipments can continue once Ukraine clears the Black Sea of mines and approaching ships can be screened for weapons. Sergey Lavrov, the foreign minister of Russia, said that his country would “make all necessary efforts to guarantee that the ships may depart there freely” and would not “abuse” its naval superiority.

Western and Ukrainian authorities have doubts about the guarantee. Mevlut Cavusoglu, the Turkish foreign minister, stated last week that since the locations of the explosive devices are known, it would be possible to build secure passageways without first having to clear sea mines.

However, there would still be unanswered issues, such as whether insurance companies would cover ships. The only option, according to Dmytrasevych, is to beat Russia and open up the ports. “No other interim measures, like humanitarian corridors, will address the issue,” he told the EU agricultural ministers this week.

Before the invasion, food prices were rising as a result of factors including poor harvests and severe weather that were reducing supply, while the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant positive impact on worldwide demand.

Glauber mentioned a year with weak wheat harvests in the United States and Canada as well as a drought that reduced Brazil’s soybean crops. A record heat wave in India in March reduced grain yields and the Horn of Africa is currently experiencing one of its worst droughts in four decades, both of which are being exacerbated by climate change.

This has precluded other major grain-producing nations from filling the gaps, combined with rising fuel and fertilizer prices. The poor nations that are most at risk from price increases and shortages are the primary recipients of Ukraine and Russia’s basic exports.

Wheat, corn, and sunflower oil from the two warring countries are greatly relied upon by nations like Somalia, Libya, Lebanon, Egypt, and Sudan. The poor are bearing the burden, according to Glauber. Without a doubt, that is a humanitarian disaster.

In addition to the risk of hunger, many nations face the possibility of political instability due to rising food costs. They contributed to the Arab Spring, and there are concerns that it may happen again.

According to Glauber, the governments of emerging nations must either allow food prices to grow or subsidize expenses. He said that Egypt, the top importer of wheat worldwide, can afford to tolerate rising food prices.

Famine and starvation are prevalent in that region of Africa. While millions of animals that households depend on for milk and meat have perished, prices for basic commodities like wheat and cooking oil have, in some cases, more than doubled. The Russia-Ukraine war occurred on top of years of local problems in Sudan and Yemen.

UNICEF warns that there would be an “explosion of child deaths” if the world merely pays attention to the conflict in Ukraine and does nothing. According to estimates from U.N. agencies, 19 million Yemenis will likely endure food insecurity this year, 18 million Sudanese might experience severe hunger by September, and more than 200,000 people in Somalia risk “catastrophic famine and starvation.

Antonio Guterres, the secretary-general of the United Nations, has been attempting for weeks to reach a deal that would allow Ukraine to move goods out of the vital port of Odesa and unblock Russian deliveries of grain and fertilizer. But development has been gradual.

In the meantime, a sizable amount of grain gets trapped in Ukrainian silos or fields. And there’s more to come: the winter wheat harvest in Ukraine will shortly begin, placing more strain on storage facilities despite the likelihood that some fields will remain UN harvested due to conflict.

Due to the disruption of transportation lines, Serhiy Hrebtsov cannot sell plenty of grain at his farm in the Donbas area. Prices are so low because there are so few purchasers that farming is not viable.

To handle the differing rail gauges between Ukraine and Europe, U.S. President Joe Biden said he is collaborating with European allies on a proposal to erect temporary silos on Ukraine’s borders, notably those with Poland.

Grain may be moved into the silos with this theory, and then “into vehicles in Europe, transporting it to the ocean, and then transporting it throughout the world. However, it takes time. In a speech on Tuesday, he stated

According to Dmytrasevych, after Russian soldiers demolished silos or captured locations in the south and east, Ukraine’s grain storage capacity was cut by 15 million to 60 million tons.

WHAT IS MORE EXPENSIVE?

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization predicted that the global output of wheat, rice, and other grains will reach 2.78 billion tons in 2022, down 16 million tons from the previous year and the first fall in four years.

According to the FAO’s wheat price index, wheat prices have increased by 45 percent in the first three months of the year compared to the same period last year. Prices for sugar, pork, milk, fish, and vegetable oil have all increased by double digits. Vegetable oil has increased by 41%.

The price hikes are causing global inflation to accelerate, driving up the cost of food and forcing price rises on restaurant operators due to rising costs. Some nations are responding by attempting to safeguard domestic sources.

India has prohibited the shipment of live chickens, upsetting Singapore, which imports a third of its poultry from Malaysia. Malaysia has also limited the export of sugar and wheat. According to Grow Intelligence, a provider of agriculture data and analytics, Steve Mathews, a second danger is the scarcity and high cost of fertilizer, which might result in less productive fields as farmers cut corners.

Two of the key compounds in fertilizer, of which Russia is a major source, are particularly deficient. We will experience declining yields if the current potassium and phosphate scarcity persists.

edited and proofread by nikita sharma