Ghibli Obsession: How Indians Are Now Consuming More Cartoons Than Critical Thinking?

How Indians Found Time to Chase AI Cartoons While Real Problems Wait in Line!

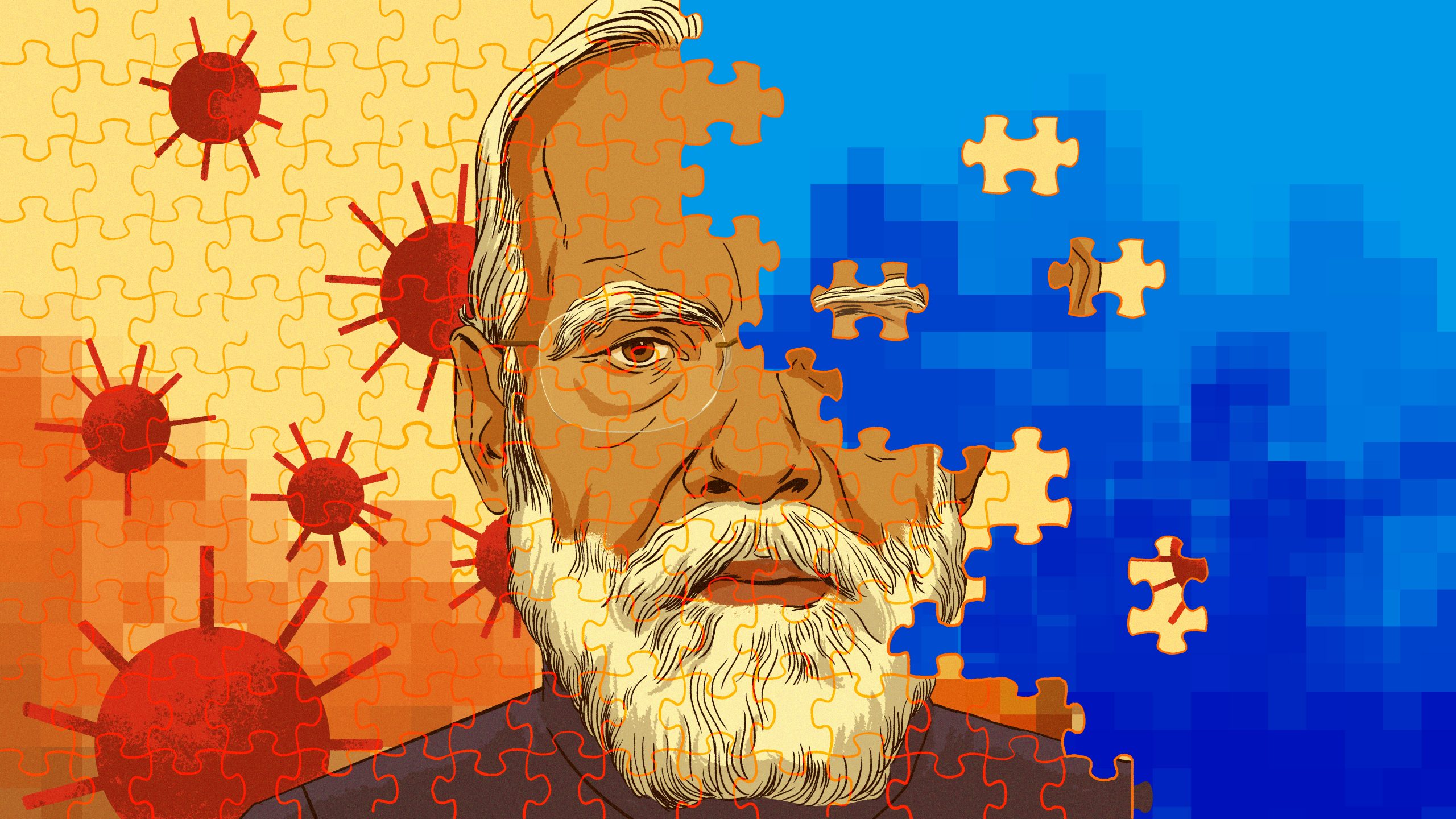

In a twist that would make even the most dedicated satirist chuckle with bewilderment, India, a nation grappling with unemployment, infrastructure challenges, and environmental crises, has somehow managed to become the fastest-growing market for OpenAI’s ChatGPT. The platform’s chief operating officer Brad Lightcap proudly announced this achievement on X, as if becoming the world’s most enthusiastic consumers of AI-generated images should be counted among our national accomplishments, right up there with space missions and cricket victories.

OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman joined the chorus, declaring India “a global leader in artificial intelligence adoption.” One can almost hear the collective sigh of relief from generations of freedom fighters who surely envisioned this exact moment when they imagined an independent India.

The primary impetus for the surge in usage is not to address climate change or income inequality. Rather, it’s creating Ghibli-style images, which are soft and dreamy cartoons like in Japanese animated movies. Over 700 million of these images have been created since March 27. That’s the reality that while issues arise like Delhi’s air and Chennai’s water worsen by the day, Indians are employing AI to create cute cartoon images of themselves in fantasy meadows.

One must not forget that Studio Ghibli’s real images typically have more profound undertones regarding being nice to the environment, lessening consumerism, and preserving cultural heritage. These undertones appear to be overlooked by the millions of individuals who are actively making their next profile picture while actual environmental and cultural heritage sites decay around them.

The geographical distribution of this obsession has an interesting story to tell in itself. According to Google Trends data, this cyber obsession is not a global phenomenon but rather South Asia-specific, led by Bangladesh followed closely by India.

Across India, Gujarat scored a neat 100 on search interest in AI “Ghibli art,” the clear reigning champion of cyber distraction and putting in doubt about the ‘so-called Gujarat Model of Development‘!

Next in line were Andaman and Nicobar Islands with 81 points, followed by Odisha, Assam, and West Bengal too, who also showed a high level of interest in turning photos into anime-style sketches rather than, for instance, tackling their local concerns of coastal erosion, flooding, or unemployment. Just imagine the irony; West Bengal became proud to become the Top 5 in Ghibli trend, and on the other hand, thousands of teachers in West Bengal lost their jobs because of what can be considered one of the biggest teaching scam of the decade.

The northeastern Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh, and Mizoram states showed the least, perhaps, they are having too many real-world problems (like, the Manipur plight) to be part of the cyber juggernaut—or maybe they’re just too intelligent to recognize a fad when they see one.

This speaks to a lot about what our country is interested in and how we use technology. While countries around the world are trying to make productive uses out of artificial intelligence to solve real social issues, South Asia, India in particular, stands out as using the lowest-level applications one can imagine. The world heat map of Google Trends attests to this discrepancy, with Western countries and Sub-Saharan Africa having less interest in this feature. One could say that these places are either too busy with utilitarian applications of technology or do not have the luxury to toy with such digital novelty—either way, they have eschewed our special brand of AI thrill.

Previous generations have often faulted young people for what they see as frivolous interests. When books became common in the 18th century, some adults worried that young people, especially women, would be corrupted by reading fiction and forget their responsibilities. When radio was the mass medium in the early 20th century, older people complained that young people were too worried about listening to shows instead of getting something productive done.

The introduction of television raised similar fears, with critics warning that young people would be “zombies” watching screens instead of learning something or engaging with other human beings. Video games in the 1980s generated new fears, as parents worried their children would spend too much time in arcade shops. And we shouldn’t forget worry in the early 2000s that texting would kill reading skills and concentration.

But there is something quite ironic in this distraction. India has long been regarded as a coming technology center, with government programs like “Digital India” and a booming IT sector that has created global tech behemoths. Indians have been urged to acquire tech skills that would fix the nation’s problems and provide employment opportunities. And yet, the majority of them appear to be squandering their time and tech expertise on creating cartoon representations of themselves and the world around them, which is nothing but a classic example of the choice of fantasy over reality. This enormous distraction comes at a peculiar time in our history.

India has extremely high youth unemployment rates, with millions of educated young people unable to find good jobs. The World Economic Forum pointed out India’s skills gap by noting that even though India has one of the largest youth populations in the world, many young people do not have the practical skills needed for new job markets. One might well wonder: If we can become the fastest-growing market for AI picture-making, couldn’t we apply that same energy and interest in technology to solve real problems? If millions can learn to make the perfect Ghibli-style self-portrait, couldn’t they also be interested in learning programming, data analysis, or digital problem-solving?

This is a trend that reflects what some call the “Bhed chaal” (herd mentality) in certain aspects of Indian culture—a tendency to follow what others are doing without using critical thinking. Just as previous generations rushed to get their children admitted to engineering or medical schools regardless of their aptitude or interest, youth today also seem to be eager to adopt digital fads. When someone puts up a Ghibli-style makeover on Instagram, many will immediately try to do their own versions, creating many cartoon avatar-like faces that ironically lose the uniqueness they are supposed to showcase.

Some apologists will perhaps say that this is just harmless fun, a fleeting diversion in otherwise difficult lives. But when a country of India’s potential and necessity becomes world-renowned for its use of digital frivolity, one cannot help but wonder if we’re getting ourselves ready for long-term success or merely constructing high-tech diversions from the work that really needs to be done. As the ancient Roman poet Juvenal cynically remarked about the values of his own people, we’ve become a people satisfied with “panem et circenses” (bread and circuses)—or in our own contemporary example, biryani and AI filters.

It is paradoxical that the young people using AI image generators are also worried about AI replacing them in the future. Instead of cultivating the special human abilities that would protect them from unemployment—like creativity, handling tough situations, and learning about feelings—they focus on technology that creates the same images using algorithms, even when it claims to be original. It is like being afraid of a big wave while swimming happily in the small water that comes ahead. So what does this portend for India’s future?

Are we bound to be a people of digital consumers, not producers? Will we continue to judge our technological advancement by how rapidly we adopt useless apps instead of how well we address genuine challenges? The answer probably lies between hope and despair. Each generation has its diversions, and maybe this Ghibli thing is just that, a short distraction along the way to greater interaction with technology. Or maybe it’s a canary-in-the-coal-mine warning sign of a deeper cultural drift toward digital escapism that needs to be reckoned with.

Either way, a lot of Indians are creating cartoon images of themselves in virtual spaces. Meanwhile, the actual India, with its pollution, poverty, infrastructural needs, and unrealized potential, waits for its youth to return from their virtual daydreams.

They must redirect some of that energy in the real world beyond their screens. As the adage goes, “Time and tide wait for no man”—and a country’s issues won’t wait, no matter how adorable the diversions.