Does The Absence Of Effective Trade In The Indo-Japan FTA Stem From Low-Quality Indian Products And Tariffs?

As per the data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the UNCTAD created by the international trade promotion organisation MVIRDC, India's share of Japan's merchandise imports has increased marginally since the CEPA's implementation, from 0.71% in 2011 to 0.85% in 2021.

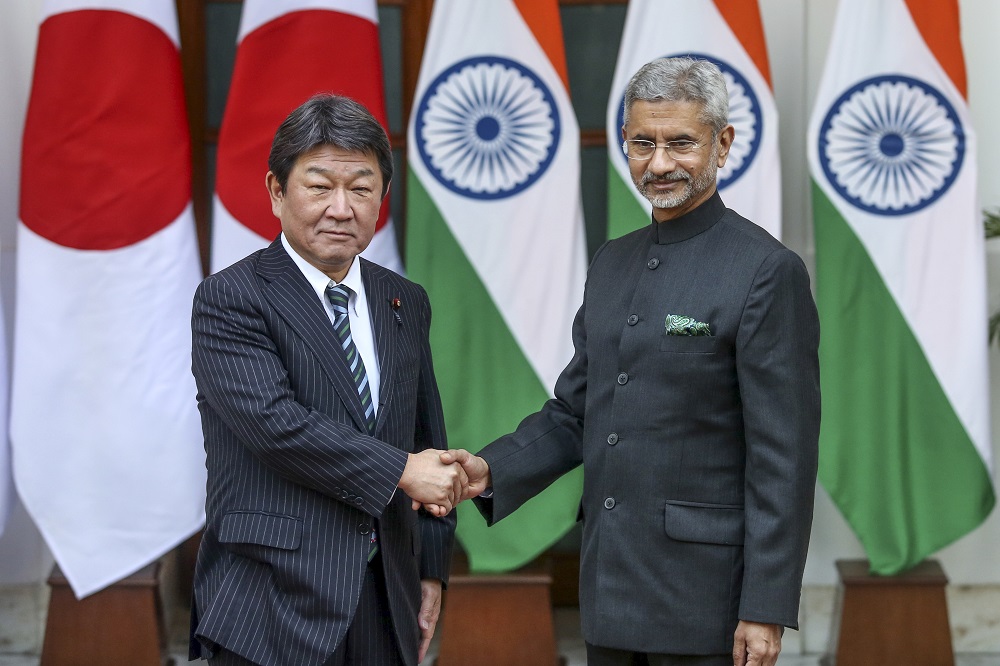

On the margins of the G7 conference in Hiroshima in May, Prime Minister Narendra Modi met with his Japanese counterpart, Fumio Kishida, to explore ways to strengthen bilateral collaboration in a variety of sectors. The Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, the CEPA between the countries is one topic worth discussing.

This 2011 free trade agreement, the FTA intends to abolish tariffs on 90% of Japanese exports to India (like auto components and electric appliances) and 97% of Indian imports (like agricultural and fishery goods).

The purpose of the treaty was to enhance bilateral trade dramatically. According to the most recent commerce ministry figures, trade between India and Japan reached a decadal high of $20.57 billion in fiscal year 2021-22. This suggests that the CEPA was a success.

However, when the data is examined closely, the story shifts dramatically. India’s exports to Japan were $6.18 billion in fiscal year 2022, while imports were $14.39 billion. This demonstrates that India’s exports have not increased as much as its imports. Why?

As per the data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the UNCTAD created by the international trade promotion organisation MVIRDC, India’s share of Japan’s merchandise imports has increased marginally since the CEPA’s implementation, from 0.71% in 2011 to 0.85% in 2021. In 2021, India’s percentage of exports to other G7 countries was 1.35% for Italy, 0.87% for France, 1.50% for the UK, and 2.47% for the US. As a result, some argue that India did not benefit as much as it should have from the Japan arrangement.

Notably, Japan is the only country in the G7 group with whom India has a specific trade deal. The 2011 FTA addresses goods trade, services trade, investments, intellectual property rights, customs processes, and other trade problems. According to reports, New Delhi’s delegates highlighted concerns about Tokyo’s restrictive practices during a World Trade Organisation (WTO) trade policy review in May. According to the representatives, the limitations have raised the cost burden, created impediments to exports from India to Japan, and stifled the expansion of bilateral economic cooperation.

Is Quality requirements an issue with Indian products?

Over the years, stringent quality standards and non-tariff barriers have hampered India’s exports to Japan, says Vijay Kalantri, Chairman of the MVIRDC World Trade Centre Mumbai. Other specialists share this viewpoint also. Aside from trade restrictions, Japan has enhanced product-specific and technical criteria for the items it imports. According to trade experts, many small and medium-sized businesses in India cannot produce such high-quality goods. As a result, they are having difficulty exporting items to Japan. Sorry to say we do not have such high-quality standards!

According to industry stakeholders, India’s exports to Japan are low-value commodities, while its imports are high-value items, resulting in a trade deficit. According to trade ministry data, India’s exports to Japan were $5.18 billion in the fiscal year 2022-23, while imports from Japan were $11.97 billion. Between 2011-12 and 2021-22, imports increased at a CAGR of 1.6%, while exports decreased by 0.3%. The trade gap has developed unfavourably for India, not just because of industrial inefficiencies but also because of the lack of an environment to foster the necessary competencies.

Let’s use the example of India’s toy sector to demonstrate how the government has failed to capitalise on the CEPA. Lab-verified compliance with Sections IV and V of the Japan Food Sanitation Law (JFSL) is required for eligible children’s goods before they may enter the Japanese market under the Japan Food Sanitation Law (JFSL). Furthermore, all conforming toys must have the Safety Toy Mark (ST Mark). The Japan Toys Association has designated agencies to test and certify toys for the Japanese market. Regrettably, no agencies or laboratories in India are accredited to conduct such examinations. Because of this market gap, no Indian firm, particularly MSMEs, could obtain direction to acquire the necessary competencies.

As a result, toy producers must send their complete shipment to Japan for lab testing and certification, causing unnecessary delays and hefty extra expenses for exporters. This also implies that if the shipment is refused there, the producer or exporter will cover the cost. This is a problem since India’s toy exports have risen by 61% in three years, from $202 million in FY19 to $326 million in FY22. However, the government has been unable to leverage this with Japan.

Exports from India are competitive.

According to experts, India’s exports to Japan are less competitive than other large exporters such as China. This is primarily due to India’s higher basic input costs. High logistics, electricity, and capital expenses add to exporters’ burden. India must concentrate on enhancing the quality of its exporting products to enter mature markets such as Japan.

According to WTC Mumbai’s study report, India’s export growth to Japan has been the weakest among the G7 countries, increasing by just 8.7% from $5.6 billion in 2011 to $6 billion in 2021, with a CAGR of only 0.76% over the previous decade.

According to experts, one of the critical reasons for the poor development of Indian exports is the high most favoured country (MFN) tariffs. Tariffs on imports from FTA countries are lower. On average, India’s MFN tariff is over 15%, whereas Japan’s MFN duty is around 3.5%, yet both countries already have bilateral trade. Now that Japan has dropped tariffs to zero, India’s exporters gain 3.5%, but they won’t be able to flood the market to take advantage of it. On the other hand, 15% is a significant hurdle for Japanese exporters. They might flood the market with items once India’s tariffs are reduced to zero.

First, know the need.

According to a former Indian Trade Service official, there was a lack of awareness of what the Japanese wanted. Hence specific export categories were unable to capitalise on the trade potential. He cites the textile industry, where India is a worldwide leader, to demonstrate how the chance was lost.

India and Japan removed all garment tariffs on the first day of the FTA. India anticipated an increase in exports, but that did not occur. Between 2007-09 and 2019-21, India’s garment exports climbed from $121 million to barely $197 million. Despite the FTA, exports have not increased. While customers from the EU or the US search for Indian companies that follow their rules, the Japanese focus on process improvement on the supplier’s shop floor.

Because the market is limited, most Indian exporters did not think it profitable to fulfil the criteria of prospective Japanese customers, and not enough study was done on the requirements of Japanese buyers and zero tariffs were considered as a “good enough” benefit. Because Indian exporters have generally focused on the Western market, they have been unable to expand their presence in Japan even when there was a chance. Now, China and ASEAN have already captured the Japanese market.

The export potential has yet to be realised.

According to the WTC report, India has a $20 billion untapped export potential in Japan. “In theory, under the current trade agreement, India has an untapped export potential to Japan of $119 billion.” This is Japan’s surplus import from other countries over what India supplies. More practically, India’s genuine untapped export potential may be roughly $20.5 billion for 474 commodities that India may investigate in the near to medium term.

The textile and apparel industries have the most untapped export potential ($7.2 billion), followed by chemicals and pharmaceuticals ($4.6 billion) and energy ($3.4 billion). According to the research, India has demonstrated global competitiveness in these commodities, with above 5% world share in each of these 474 goods.

Experts say that India-Japan CEPA should be reconsidered. To eliminate supply-side rigidities and make India’s export competitive worldwide, policymakers must implement comprehensive manufacturing reforms, including land, labour, and capital, they argue. When it was first launched in 2011, the trade agreement included about 1,962 tariff categories from India that were eligible for zero import charges. The number of tariff lines in the zero-duty category climbed 13% in 2021, from 1,962 to 2,218. However, the importance of the commodities covered by the zero-duty band has dwindled during the last decade.

These 2,218 tariff lines’ percentage of India’s worldwide product exports declined 10.9% from 47% in 2011 to 36.1% in 2021. Their percentage of Japan’s global import basket fell 4.8% during the same time, from 20.6% to 15.7%.

Experts suggest India should identify sectors where Japan’s imports are expanding and consider how to market such items. Export promotion councils collaborate with local firms to better understand many elements of product, quality, and Japanese customer criteria. These product items should also receive specific interventions. The councils should send product-specific delegations to Japan to actively sell the items. Programmes such as exhibits and trade fairs can augment this. Such actions may present chances for Indian exporters.

Policy emphasis.

According to experts, more and more district-level industrial groups should take the initiative and send delegations to Japanese enterprises. MSMEs should take the initiative in meeting Japan’s demands. There is a wide range of commodities available, including marine items, textiles, spices, grains, and iron and steel products.

Conclusion.

Industry watchers also believe that India might benefit from policy changes. Consider the case of textiles to illustrate that duty drawback benefits allow firms to export at a lower price than what is available in the domestic market. This decreases the supply of inputs for high-value-added garment exports. Remove any incentives for low-value-added input exports. Increase the number of factories that are fast fashion industry (FFI) certified. There are 1,200 complying plants in India that offer cotton goods to FFI and other significant clients.

As they take most orders, they aim to make more units FFI compatible. The Japan CEPA teaches policymakers what they should not overlook when signing FTAs. If these lessons are not learned, a bilateral agreement will only benefit one party.

Proofread & Published by Naveenika Chauhan