Do Not Book A Judge By His Cover. Dig Deeper To Know The Dark Chapters!

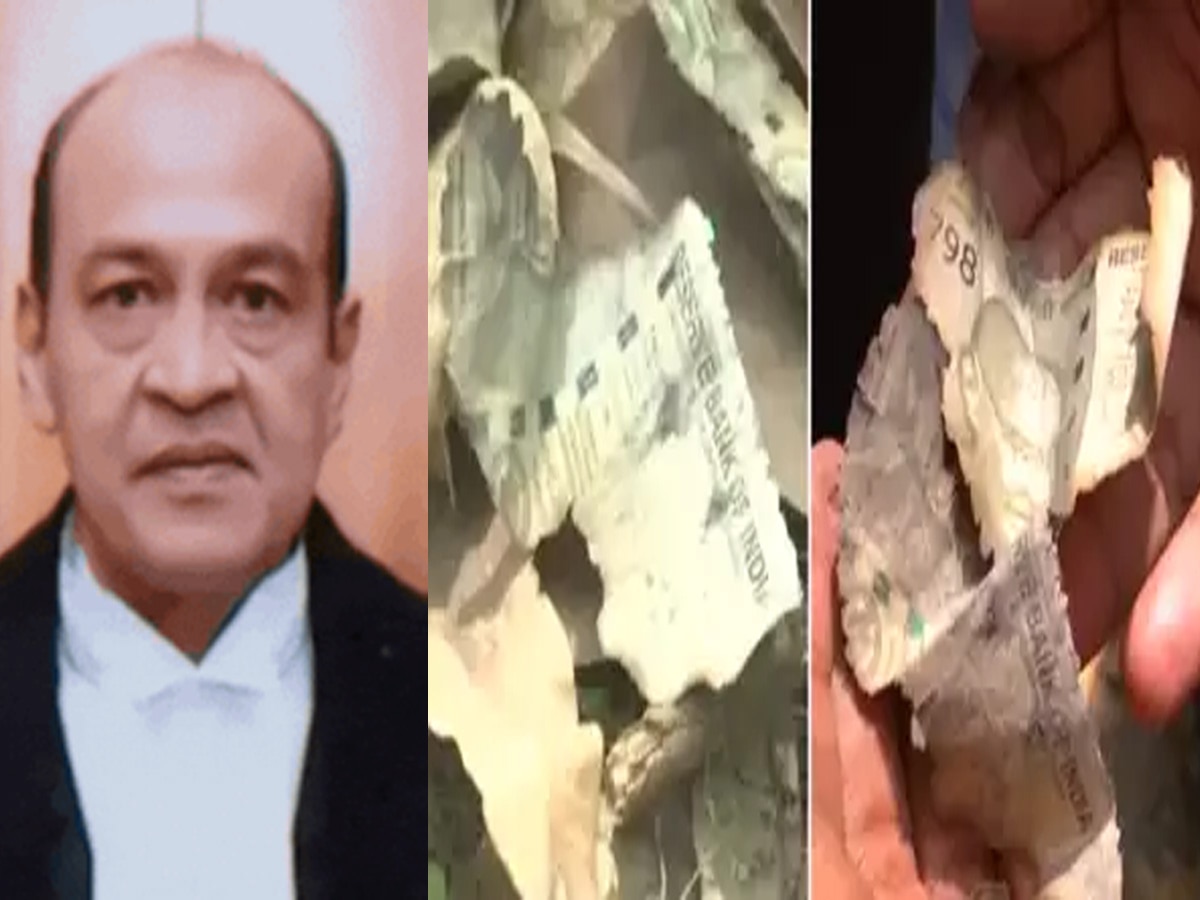

The recent incident of cash burning at Justice Yashwant Verma’s home of Delhi High Court is no small matter; it is a cyclone that holds even deeper levels of danger that could shake India’s judicial confidence.

Imagine you are entering a judge’s home, the second sacred place where truth is held supreme and justice is believed to be blind (earlier) and impartial. Then suddenly, you notice something strange brewing behind those holy walls- not a handful of rupees, but burning a huge pile of cash!

While you start ignoring that this as an open secret, the Delhi Fire Department’s head comes and declares ‘there is no cash found’. You again ignore this as harsh reality. Then again the apex court of the nation releases video of burnt cash. A common man again ignores this as brutal reality and moves ahead in his day towards work.

At every point, where WE, THE PEOPLE OF INDIA, should be worried about these situations, we have accepted them as ‘something usual’. Why?

- How could we accept the ‘illegal cash’ found at a judge’s home to be normal?

- How could we believe that the fire department head’s words were normal?

Perhaps, because, we, the citizens of India has accepted ‘corruption as an inherent property of judiciary‘, and nothing will happen because, the last point of justice, temple of justice, if jeopardised, then we have no road to justice! When a large sum of cash is seized from politicians, builders, or bureaucrats, citizens accept it as normal since they see it in their everyday lives.

Corruption affects all parts of a community. When bureaucracy, politics, medicine, engineering, media, and accounting all have their fair share of corruption, it is unusual for just one component – the judiciary- to be immune to the virus that is afflicting society. It is like seeing a sad and hilarious show where the punchline is how our democratic institutions are crumbling bit by bit. If a society has become calm about corruption scandals over the years, this is not a good sign of democracy.

How does the system handle it?

With an extremely Indian solution – a hush transfer. They transfer the problem away, cover it up, and act like nothing is happening! The Supreme Court Collegium’s reaction is like that eternal Indian uncle who, when confronted with an unpleasant reality, just shifts the discussion or tells the troublemaker to get out. “Beta, let’s not discuss this” – but “beta” here is a sitting high court judge, and “this” is a potential breach of judicial integrity. Social media is already speculating on how this will finish, much like a regular high-level investigation that would span years, with people forever waiting for specifics of the crime to be revealed and the penalty elusive.

However, one key subject that has received little attention due to the ivory tower in which the court is housed is resurfacing: the collegium system, which allows judges to nominate themselves. Many have described it as an exclusive club of a few unelected individuals with immense power. Following the revelation of this episode, Harish Salve, a senior lawyer, and Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar both questioned the collegium method of selection.

The problem here is not one judge or one case. It is one of a rot that has been festering in our justice system for decades. The Indian judicial appointment process is more like a handbook for a secret society – opaque, cryptic, and seemingly answerable to no one. The Collegium system, which sounds more like a mysterious global council than a judicial selection mechanism, is so opaque that Cold War-era spy rings would be transparent by comparison.

The founding fathers did not anticipate Collegium. The Indian Constitution does not allow for it, therefore to guarantee that the judiciary receives additional protection, constitutional revisions are more stringent than in other parts. This grouping emerged in the 1990s, when the Supreme Court, in the second judge’s case, pulled from the ‘fundamental structure theory’ to conclude that consultation did not imply acquiescence.

Experts have stated that the fundamental structural doctrine that resulted from the Kesavananda Barati case was problematic due to the procedure by which the majority’s viewpoint was reached. Since the 1990s, the Parliament has sought at least four times to give itself a role in judicial appointments.

Do you remember the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC)? It was a good idea for more transparency, however, it was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court leaning on the basic structure doctrine even though both the houses of Parliament and majority of states endorsed it. The Supreme Court quickly killed it to preserve the ‘judicial independence’ of the courts. But independent of what? It is like a chef not allowing anyone to see the kitchen and yet trusting diners to believe the food without question.

The Collegium does not publish formal criteria, nor do they record debates or provide public justifications for appointments, promotions, or transfers. For example, when a judge is passed to the top in the Supreme Court, the Collegium is under no need to disclose any rationale. This confidentiality simply adds to concerns that judge nominations are based on personal loyalty, ideological alignments, and internal politics rather than merit. Aside from judicial appointments, the promotion of advocates to “Senior Advocates” takes place behind closed doors. There is no explanation as to why an advocate is raised or held back. The elevation method is sometimes criticized for being motivated by corridor politics, resulting in inexplicable exclusivity.

Another hotly debated issue is the public disclosure of assets by members of the judiciary. The Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act of 2013 requires public servants to declare their assets and liabilities, as well as those of their wives and dependent children. “Public servant” refers to someone who works for the government or is paid by the government to fulfill public duties. While this includes MPs and military people, it also includes anyone authorized by law to perform judicial tasks. As a result, it is applicable to judges from all backgrounds.

While judges declare their assets, unlike other public officers, these declarations are not automatically open to the public. According to official statistics from 2024, just 98 of the 749 judges who are now serving in 25 high courts have assets that are publicly disclosed. The disparity in treatment between public officials and the court clearly establishes a class inside a class whose existence is baseless.

Compare it with what is done all around the world. In America, after Watergate scandal, judges had to disclose their finances. As a result, the financial disclosures of judges and their family are publicly available on the United States Courts website. Importantly, judges are also safeguarded by warning the public that using these financial data for any illegal or commercial purpose other than news and communication media broadcast to the general public is prohibited. The European Union also has such open laws. But India? We are still shying away from open debate on judicial accountability, concealing it more than we are concealing our nuclear codes.

The most infuriating part isn’t really the lack of transparency – it’s the subtext. By not publishing asset declarations, the judiciary sends a chilling message: “Trust us because we say so.” But trust isn’t something you need; it’s something you earn.

Each no rational transfer of judge, each enigmatic pile of cash, each secretive, sometimes seductive, favourable appointments chips away at the public’s trust in our judicial system.

We are not calling for a witch hunt. No one wants judges to feel constantly under observation. But in a democracy, public officials – especially those wielding the vast authority of interpreting the law – must be held accountable. Their integrity is not a personal virtue; it is the foundation of our constitutional system.

The response is simple. Transparent appointment procedures. Compulsory and publicly available asset disclosures with proper privacy protection. Uncomplicated disciplinary procedures that do not use the handy “transfer” trick. These are not challenges to judicial independence; they are the tools that help defend it.

Judges possess immense power, and with great power, comes great responsibilty, and accountability!

The gravity of their responsibilities requires appropriateness. Will this incident serve not only as a reminder but also as a catalyst for implementing long-overdue judicial reforms?

As ‘bhartiya janta’, we observe the slow disintegration of our institutions, switching between black humor and honest worry.

- Will the courts correct themselves?

- Will real change come from within?

- Or will we just keep playing this complicated game, where responsibility remains a mirage?

The fire in Justice Varma’s home might have been calmed, but the fire of judicial decay continues to burn. And until we address these fundamental questions, our faith in justice will be as fragile as a house of cards in a monsoon wind!