Scientists Believe the Discovery of Hidden Genes In COVID-19 May Prove A Useful Addition to Our Biology

Scientists Believe the Discovery of Hidden Genes In COVID-19 May Prove A Useful Addition to Our Biology

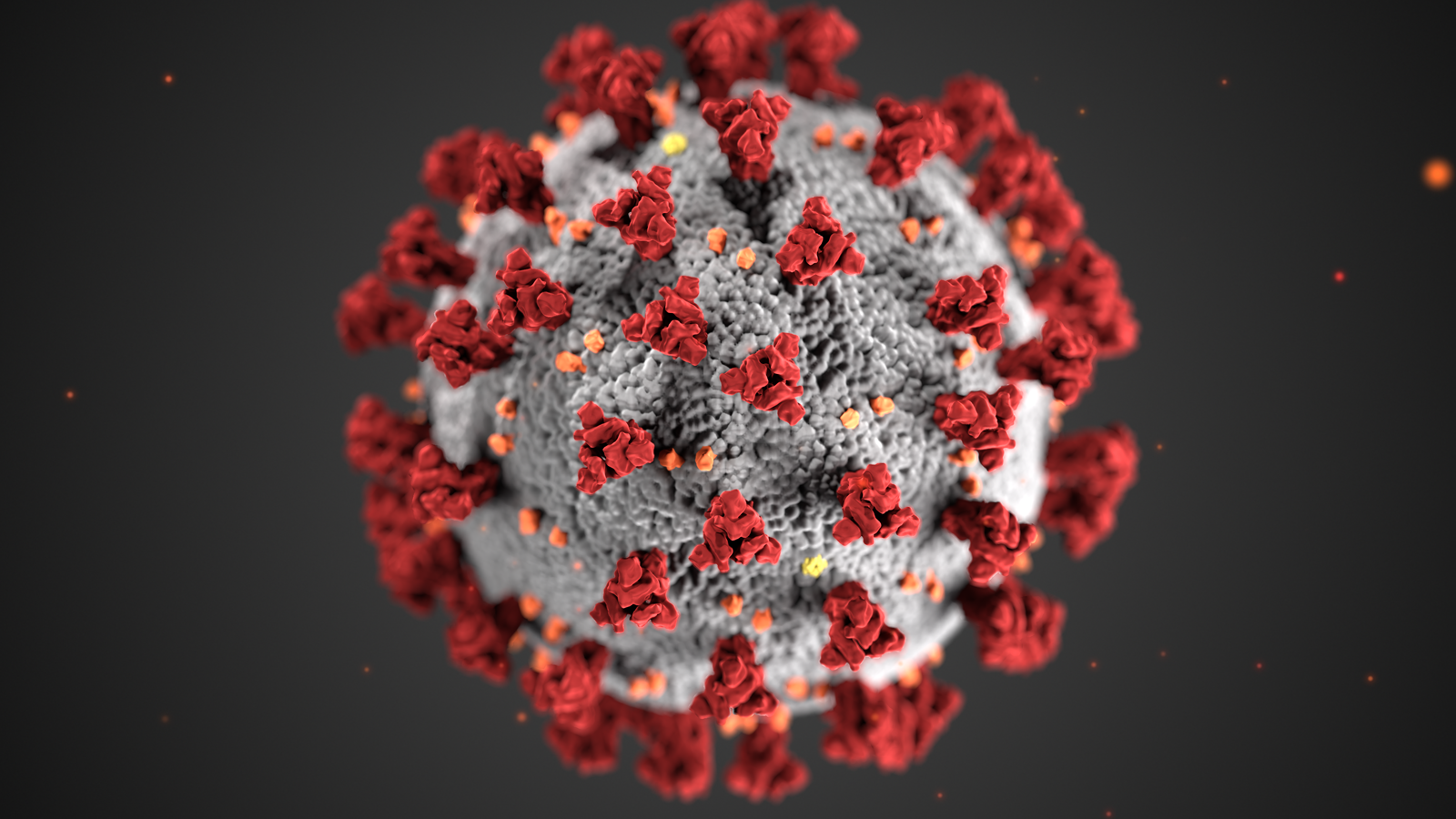

Scientists have recently uncovered a hidden gene present in the Covid-19 genome which may contribute to the unique biology and pandemic potential of the novel strain; according to the scientists, including those from the American Museum of Natural History in the US, knowing more about the 15 genes that make up the coronavirus genome could have a significant impact on developing drugs and vaccines to combat the virus.

Published in the journal eLife, the current study shows that researchers described overlapping, nested genes – or “genes within genes” – in the virus which they believe play a role in the replication of the virus within host cells. The research team identified a new overlapping gene – ORF3d – in the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 that has the potential to encode a protein that is longer than expected.

“Overlapping genes may be one among an arsenal of ways in which coronaviruses have evolved to replicate efficiently, thwart host immunity, or get themselves transmitted,” revealed the study’s lead author, Chase Nelson, a visiting scientist from the American Museum of Natural History. “Knowing that overlapping genes exist and how they function may reveal new avenues for coronavirus control, for example through antiviral drugs.” They said ORF3d is also present in a previously discovered pangolin coronavirus, indicating the gene may have undergone changes during the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

According to the study, ORF3d has been independently identified and shown to elicit a strong antibody response in COVID-19 patients, demonstrating that the protein produced from the new gene is manufactured during human infection. In addition, ORF3d has been independently identified and shown to elicit a strong antibody response in COVID-19 patients, demonstrating that the new gene’s protein is manufactured during human infection.

“We don’t yet know its function or if there’s clinical significance,” Nelson reported, “but we predict this gene is relatively unlikely to be detected by a T-cell response, in contrast to the antibody response. And maybe that has something to do with how the gene was able to arise. Missing overlapping genes puts us in peril of overlooking important aspects of viral biology. In terms of genome size, SARS-CoV-2 and its relatives are among the longest RNA viruses that exist. They are thus perhaps more prone to ‘genomic trickery’ than other RNA viruses.”

At a first glance, genes seem like they are a written language – in that they are made of strings of letters. For instance, in RNA viruses, the nucleotides A, U, G, and C convey all the information we need to know about that specific RNA strain. But while the units of language – words – are discrete and non-overlapping, genes can be overlapping and multifunctional, with information cryptically encoded depending on where you start “reading.” Overlapping genes are hard to spot, and most scientific computer programs are not designed to find them.

However, they are common in viruses. This is partly because RNA viruses have a high mutation rate, so they tend to keep their gene count low to prevent a large number of mutations. As a result, viruses have evolved into a data compression system of sorts, in which one letter in its genome can contribute to two or even three different genes.

Prior to the pandemic, while working at the Museum of Natural History as a Gerstner Scholar in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Nelson developed a computer program that screens genomes for patterns of genetic change that are unique to overlapping genes. For this study, Nelson teamed up with colleagues from institutions including the Technical University of Munich and the University of California, Berkeley, to apply this software and other methods to the wealth of new sequence data available for SARS-CoV-2.

“The COVID-19 virus belongs to the family of coronaviruses, which are basically a large family of viruses that cause many ailments from the common cold to more severe diseases like Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV). Till date, only six types of coronaviruses are known to infect people. The virus that causes COVID-19 is the seventh and quite unlike the others,” reported The Health Site.

Researchers do not yet know its function or if there’s any clinical significance in the findings. But they predict this gene is relatively unlikely to be detected by a T-cell response, in contrast to the antibody response. And maybe that has something to do with how the gene was able to arise. The group is hopeful that other scientists will investigate the gene they discovered in the lab to define its function and possibly determine what role it might have played in the emergence of the pandemic virus.