Adolescence: A Movie That Showed Mutilated Masculine Mirror – How Cinema Reflects The Crisis Of Adolescent Manhood

Within each young boy is a rich, complex space—a forest of emotions, questions, vulnerabilities, and dreams as wondrous as any natural wonder we battle hard to preserve. But as we fiercely battle to protect the old redwoods and the Amazon rainforest, we too readily forget the equally vital worlds developing within our sons, brothers, and friends. This terrain of emotions so full of life and vital to being human, we too readily cut down in the name of “becoming a man”—an age-old process with such firm conviction we hardly ever pause to consider what it costs.

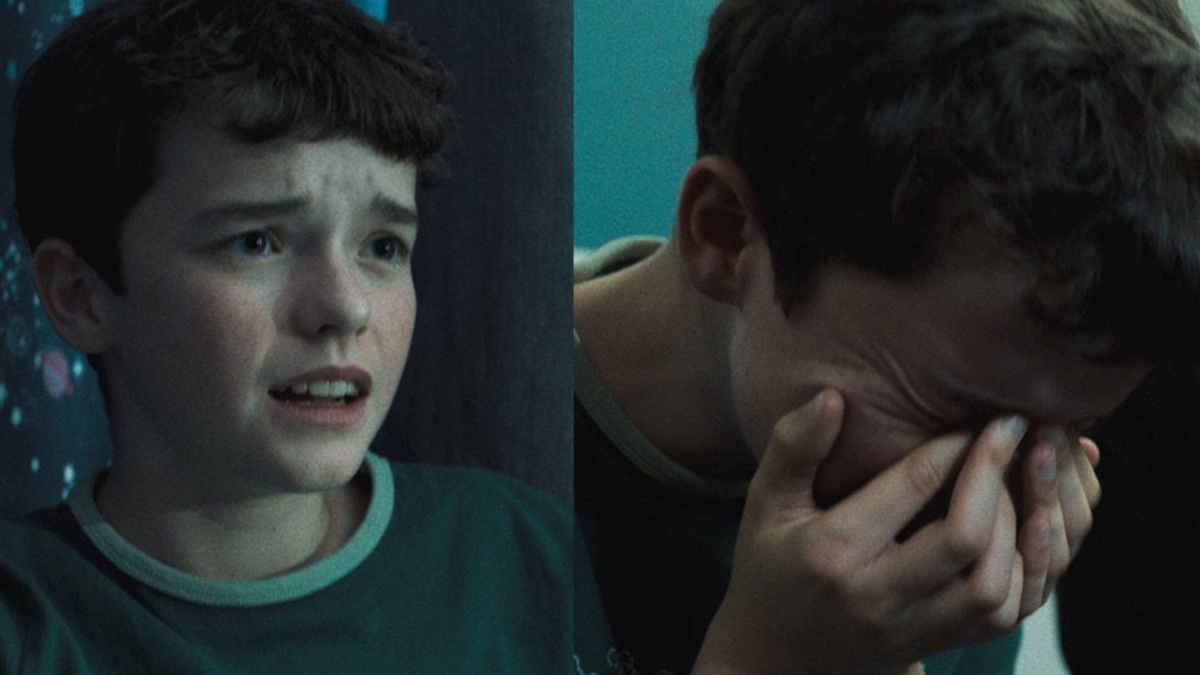

The Netflix movie “Adolescence” worked like a mirror held before us, reflecting not only the challenging journey of its protagonists but also the common narrative of masculinity that has evolved over many young lives.

What touched me the most about this movie wasn’t a thrilling plot point or a huge cinematic moment, but the aching truthfulness in how it portrayed how boys silently shatter. There isn’t a thunderous crash, no one specific moment when all goes out of way; instead, cracks slowly develop, nearly imperceptible, tiny fissures spreading under the surface where no one will look, where everyone is too caught up celebrating the false facade of “strength” to catch sight of the face behind it crumbling.

Think for a moment about something that we pay little attention to: most of the men in our lives are adult boys who were never allowed to fully feel. They were given strength at a very early age not as something to foster, but as something to wield without complaint or question. “Keep it strong,” they are taught from the age that they can understand. “Never let it go, even when you are tired, even when you do not know what you are fighting for.” In this implicit lesson of boyhood, crying is weak, having time to think about feelings is lazy, and feeling deeply a failure.

The acts we most want to label as problematic in adolescent boys like experimenting with drugs, acting out, and the rage that bursts out sometimes are not wild times or personality defects to be fixed by stricter rules. If we listen, we may recognize these as shrewd survival strategies.

These are the shifts that occur when a boy is instructed to “grow up” but not taught what exactly that means, aside from keeping his real feelings hidden. As James Baldwin wrote, “Children have never been very good at listening to their elders, but they have never failed to imitate them.” What are our boys learning when they watch the men in their lives? Too often, it’s the way of shutting down their feelings.

The actual tragedy isn’t what we’re teaching boys to be, but what we’re teaching them to leave behind. We’re not actually raising boys in our society; we’re conditioning them to perform; toughening them up for their work as providers, warriors, and champions, but not allowing them to become complete human beings who are able to feel all sorts of emotions. Shakespeare wrote to us that “all the world’s a stage,” but for young boys, the play continues and continues, the curtain never falls, and the actor never gets to exit their part, even when alone.

This is not so much a crisis of manhood, though some would argue that. The problem is not being male; instead, it’s the profound silence regarding what it means to be a man. It’s emotional deprivation disguised as discipline, packaged as strength, and enforced through shame.

Listen carefully to the quiet places of “Adolescence,” and you’ll hear the unspoken truth that boys live without a named grief, a narrative, and tragically, without a safe place. That unnamed grief becomes the unseen support of their manhood, shaping their decisions, relationships, and sense of themselves in ways that they may never fully comprehend. This is where the true agony lies, not in the expression of violence, but in the interior breakdown that leads to it.

“Adolescence” made us think of something bigger than one movie. We so desperately need to create a world where boys don’t have to yell or stay silent to get through their feelings. We need places where they can be bewildered without shame, where they can be exposed without being punished, and where they can be silent without being condemned. They need to be able to just be boys—messy, changing, sometimes perplexing, and whole—for as long as possible, without being punished for not conforming to strict ideas of how they should feel at a certain age.

The history of human beings is the story of how we’ve known and become human. Traditional communities in ancient times went through the deep shift from boy to man through initiation—initiatory rituals marking the seriousness as well as beauty of such a transition. In cultures all around the globe, there were rituals marking the emotional and spiritual aspect of becoming a man, rather than the economic or physical aspect. These initiation rituals reminded us of something that we’ve lost: that to become a full human being requires guidance, community, acknowledgment of fear, and a place where one can be vulnerable.

But in our haste to be more efficient and up-to-date, we simplified this process in ways that have left men feeling hollow. We traded wisdom for getting the job done, ritual for routine, and meaning for metrics. Now, a boy’s journey to manhood is less following a well-trod road through the woods with map and companion, and more being abandoned in the woods with only a vague command to “be a man” echoing in his mind.

More recent research in psychology and neuroscience has begun quantifying what many have intuited, that suppressing emotions can cause serious damage to mental and physical well-being. Research indicates that men who adhere to strict traditional norms about masculinity, which suppress the expression of emotions, have elevated levels of depression, alcohol and drug abuse, and suicidal ideation. The statistics cry out: men kill themselves far more frequently than females in most nations and age groups. Each of these statistics is a tale that likely started when they were boys, with instructions on what feelings were acceptable to express and which were not.

This is not about building a generation of weaker, less capable men. It’s actually the opposite; it’s about acknowledging that strength is being able to feel, being emotionally able, and connect authentically with other human beings. It’s about acknowledging that vulnerability is not a weakness but the basis of courage, as Brené Brown has so clearly explicated in her research. The boy who is able to identify and admit his feelings does not become less of a man—he becomes more human. It has nothing to do with physical strength and everything to do with emotional and psychological strength.

When I think about how this film resonates with people, I remember that this speech is not just about entertainment; it speaks to something essential about who we are and who we might become.

This is not just about a Netflix movie that affected us; it’s about the boy one might have been, with weights that were too heavy to say. It’s about the friend who slowly pulled in on himself until one day we didn’t know how to reach him anymore. It’s about the son we might raise or the brother we no longer call because he always says he’s “fine.” These boys and men in our lives don’t need advice or orders; they need space. Space to breathe, to feel, to fail, to share, to step back, and to emerge again on their own terms.

As we move forward, the most effective way to love the boys in our lives may be to simply be present for them; to observe their path without attempting to alter it. We may require less “manning up” and more gentle support that their emotions, whatever they are, are valid and worth something. Perhaps the inner lives of our boys are not untamed territories to be conquered but living systems to be cherished; complicated, messy, always worth something.

Finally, “Adolescence” is not merely exposing our failure to adequately care for boys; it is also a chance to examine what could have been if we were brave enough to approach masculinity not as unfeeling but as mixing it in a considered manner. If we could perhaps learn to see strength not in quiet but in having the courage to tell our truth, to ask for assistance, and to be receptive even when it hurts. The film suggests what many of us have known but hardly ever said—namely, that the change we need won’t come from reversing gender roles but from reclaiming our shared humanity, with all its beautiful, messy, and indispensable feelings.