What is Japan’s answer to coal in 2021? Blue hydrogen: a solution to climate change?

Japan: As one stand on a hillside overlooking Tokyo Bay. Takao Saiki is beside him, a kindly man in his seventies usually mild-mannered.

Saiki-San is upset today.

In perfect English, he says, “It’s a total joke.”. It’s just ridiculous!”

A 1.3-gigawatt coal-fired power station under construction is blocking his view across the bay, the cause of his distress.

Rikuro Suzuki, Saiki-San’s friend, says, “It seems absurd to have coal burned for electricity generation.”. One plant alone will emit more than seven million tonnes of carbon dioxide annually.”

Suzuki-san’s point is well taken. When coal’s impact on the climate is so highly contested, shouldn’t Japan be cutting its coal consumption?

What’s the deal with coal? Hydrogen? Fukushima, the nuclear disaster of 2011.

A third of the electricity in Japan came from nuclear power in 2010, and more nuclear power is planned. After the 2011 disaster, Japan shut down all its nuclear power plants. Most of them remain closed – and reopening them is fraught with difficulty.

Instead, gas-fired power plants in Japan have been working overtime. However, natural gas is expensive, as Britain discovered recently.

Consequently, Japan built 22 new coal-fired power plants powered by coal imported from Australia. The move was economically sound. However, it was not environmentally friendly. Currently, Japan faces intense pressure regarding its coal use.

The Japanese answer is to switch to burning hydrogen or ammonia, not shutting down old coal plants and switching to renewables.

Prof Tomas Kaberger, a professor at Chalmers University, says that coal-fired power plants have begun to lose value due to electric power companies’ investments.

“This would create financial hardships for the electric power companies, banks, and pension funds. This would leave Japan in a bind.”

In either case, the plants can be readily converted to burn hydrogen or ammonia, both of which emit no CO2. Using this method seems to be an excellent choice.

There are, however, much bigger ambitions for Japan’s government. In short, Japan plans to be the first hydrogen economy globally.

Toyota is a company that specializes in making cars.

My location is a shiny new hydrogen filling station in downtown Tokyo on a sunny day. A new Toyota Mirai stands on the forecourt. This is a big luxury car about the size of a large Lexus.

My leather-clad cabin is a comfortable place to sit, so I slip into it and unlock the door. There is nothing but water dribbling on the road behind me as the car is exceptionally smooth and silent.

A zero-emission, all-electric Toyota Mirai is the company’s first car. There is no giant battery under the floor of the Mirai, unlike other electric vehicles. As an alternative, it has hydrogen tanks under the back seat and a fuel cell under the bonnet. Hydrogen is converted into electricity during the combustion process, which runs the electric motors. This same technology powered lunar missions.

Many people are baffled by this technology’s choice. Batteries are cheaper, but this technology is more expensive. Tesla’s Elon Musk called hydrogen-powered automobiles “stupid”.

According to Hisashi Nakai, the statement is not valid, Toyota’s manager of public affairs. Fuel cells have many more applications than just cars, according to him.

He tells me, “I know people have different opinions, but the important thing is to realize carbon neutrality. We must look at how to make the most of fuel cells. We strongly believe in hydrogen as an important and useful energy source.”

Toyota is planning for a future where hydrogen fuel cells are everywhere, in homes, offices, factories, and even cars. They hope to lead the charge for the new hydrogen society.

Lastly, and most importantly, what do we need to do to coal? From where is hydrogen going to come to make Japan a zero-carbon country?

Blue hydrogen is the answer.

“Green hydrogen” is hydrogen made from water with renewable energy. The downside is that green hydrogen is costly.

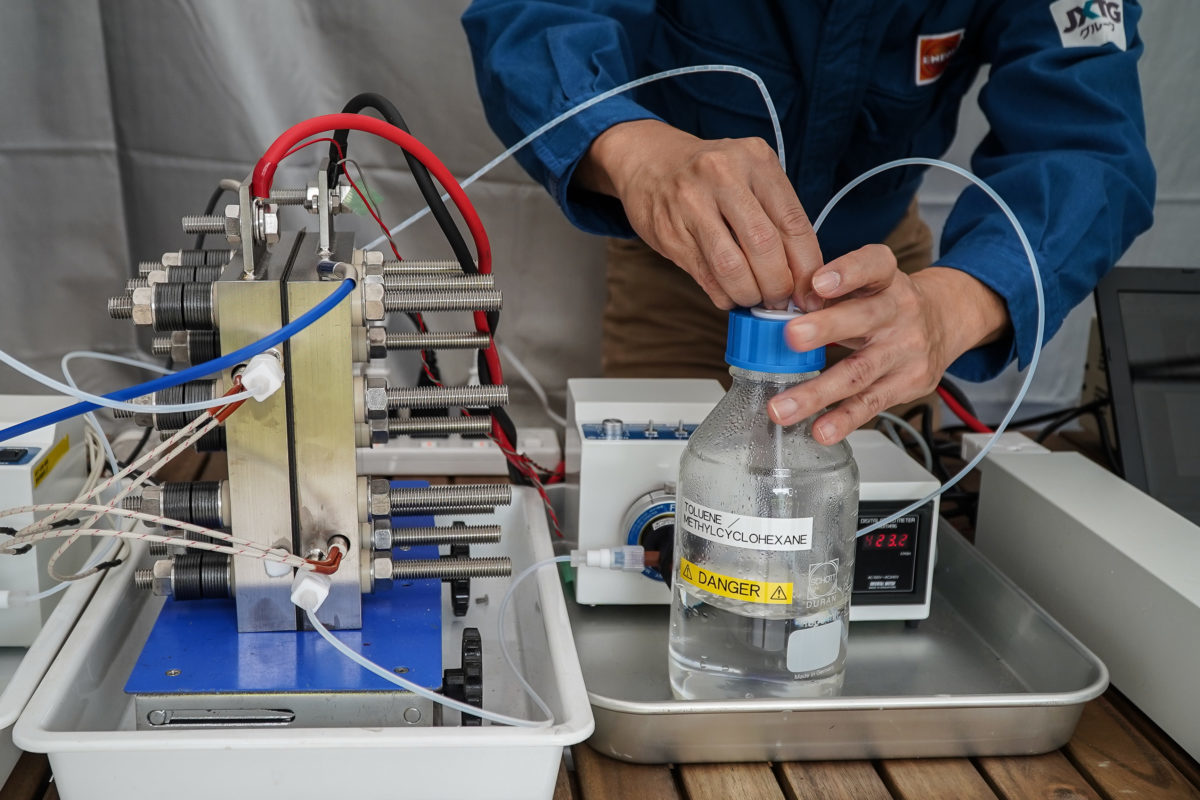

The most common materials for hydrogen production today are natural gas and coal. Both of these are inexpensive, but both produce significant greenhouse gas emissions. It is okay to call it “blue hydrogen” if you capture those greenhouse gases and bury them underground.

According to Japan, this is what it intends to do.

The state of Victoria has just opened up a new joint project between Japan and Australia to create hydrogen from brown coal, a type of coal. Liquified hydrogen is then piped into a specially built vessel for transport to Japan, where it is liquefied to minus 253C.

Where do the greenhouse gases produced at the site go? They are now released directly into the air. On the other hand, Japan and Australia say they will inject the greenhouse gas produced at the Latrobe Valley site into the seafloor off the coast at some point in the future.

These plans are horrifying to climate change campaigners. According to critics of the technology for capturing and storing greenhouse gases, Japan will have to continue digging up vast quantities of brown coal for decades to come.

Professor Kaberger says that the biggest problem with the plan is economical.

Despite technically being possible, he adds, it will always be expensive. There will always be a cost premium associated with using fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage, and renewable electricity is already cheaper than fossil fuels in many parts of the world.”

According to Prof Kaberger, the Japanese government opted for blue hydrogen ten years ago when renewables were expensive, and they are now stuck with a strategy that does not work.

He says that Japan needs cheap electricity to compete, and it needs clean electricity to have international credibility. The Japanese economy will suffer if this development is delayed.

As of yet, construction continues on Tokyo Bay’s edge. In 2023, a giant new coal-fired power plant will be operational. Approximately 40 years are expected for it to run.

Activist Hikari Matsumoto, 21, stands with us on the hillside to observe from below and admits she is ashamed of her country.

It’s so frustrating,” she says. While young people protest in other countries, Japanese youth remain silent. Our generation must speak up.”

EDITED AND PROOFREAD BY NIKITA SHARMA