Government claims a V-shaped recovery while critics a an L-shaped pattern. Who do we believe at last ? What is with these 2 alphabets of growth?

V-shaped recovery or L-shaped pattern, who do we believe?

India’s quarter one gross domestic numbers just came in last week, and everybody is running confused as to how to make sense of it. While experts have outrightly claim not to take percentages at their face value due to the low base effect and look at the actual numbers instead, the government and critics present two very extremely opposite ends of the story. The purpose of this discussion is to show that it is none of these two extremes, and somewhere in the middle. Let’s see how.

Last week, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation released information on the state of the economy, with their official quarterly calculations of the gross domestic product and gross value added. The said report had information on various verticals of the contributors of the supply side, i.e., the sectoral performance, and the credentials of the engines of demand.

Based on this information, the country could assess the weak areas, the recovery areas, and the areas that have a doubtful trajectory in the near future. It is important to properly study and analyze these figures because they form the basis of government policies for the near future, and the expert estimates for the year. However, this figure has turned out to be rather controversial, for both the ruling government and the opposition have begun to use it to further their political agenda.

A while ago, we discussed the report that the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation released and we assessed that there are two ways to read the report- on per year-on-year basis or as per quarter-on-quarter basis. According to the former, growth is measured in comparison to the same period in the last fiscal year, i.e., quarter one of fiscal year’ 21. The latter, however, draws growth on the basis of comparison from the last quarter, i.e., quarter four of financial year’ 21.

Even though the year-on-year comparison is the generally accepted and practised form of comparison in India, experts suggested that it might not be the best mechanism to study quarterly growth, and the general recovery trajectory, this time. This is in effect from the peculiar conditions that the country faced in the first quarter of last fiscal year when we were stuck in a nationwide lockdown and the economy had contracted by record numbers.

The quarter-on-quarter analysis says that the economy had contracted 17 per cent in comparison to the last quarter, while the year-on-year comparison says we have grown 20.1 per cent. Both these comparisons show conflicting implications and the political parties have started to pull on each of these extremes to further their agenda. Who, however, is correct?

Well, none of them. Both the government’s claim of a V-shaped economy and the critics’ claims of an L-shaped recovery is faulty and misleading. If you’re not sure why we are fighting over these alphabets, well, you’re not alone. Let me clarify some things for you.

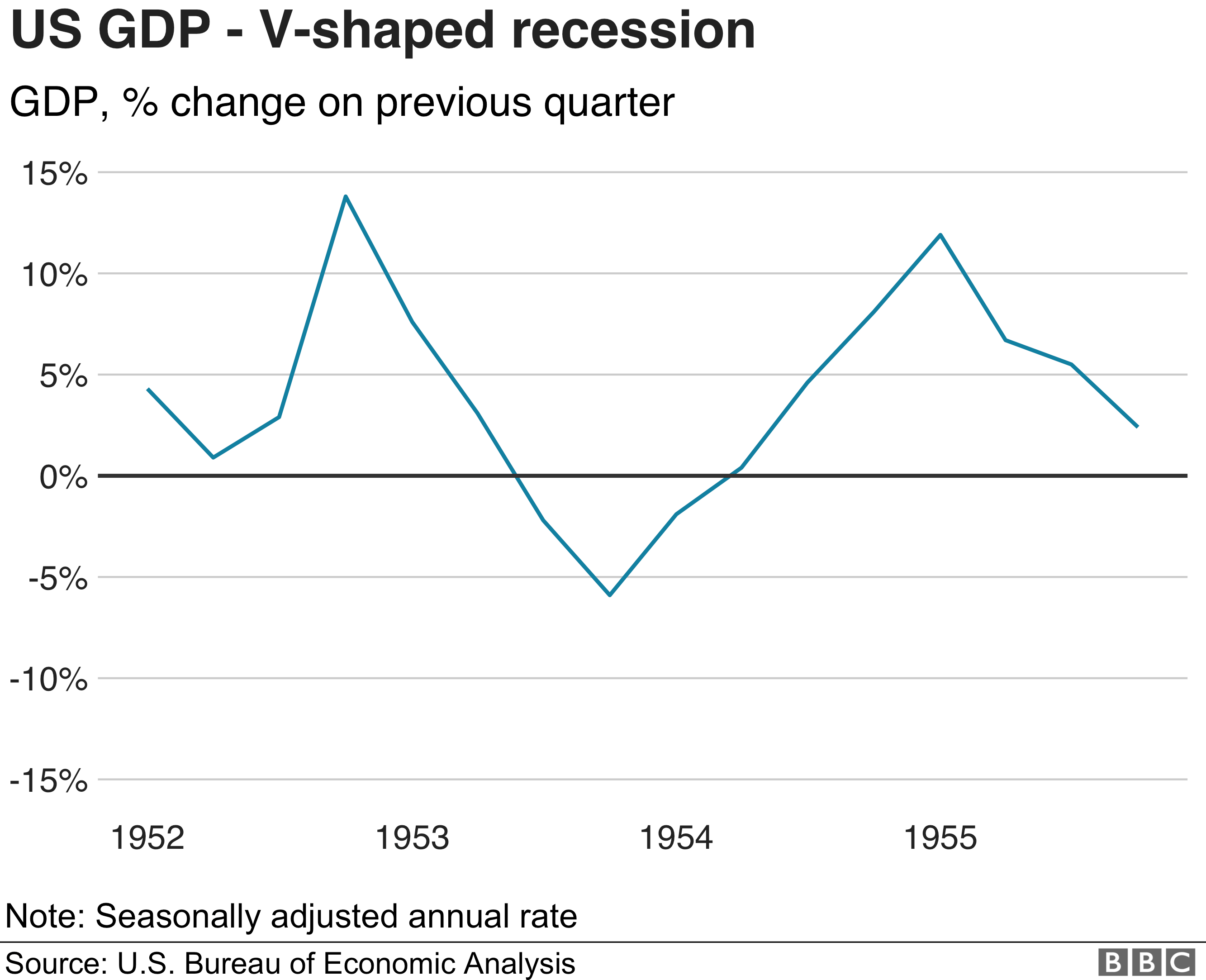

A V-shaped recovery is a form of recovery where the economy, after falling to the lost ground, quickly rises back in a way that it catches on to the pre-pandemic baseline trajectory. As opposed to the Z-shaped recovery, in which the economy rises much beyond the baseline path of the pre-pandemic level and that falls back to the normal growth rate, V-shaped recovery’s sharp comeback stays restricted at the probable growth line.

A V-shaped recovery is achieved if the loss of jobs and income during the pandemic isn’t permanent, i.e., the economy could start to get back to its original levels. In India’s case, however, this hasn’t been the reality, for the unemployment levels are still considerably high, with a loss in total jobs, and income levels, as can be seen from the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation report, still on the low. This is reflected in the crunched discretionary consumption demand and low private investment numbers of the country.

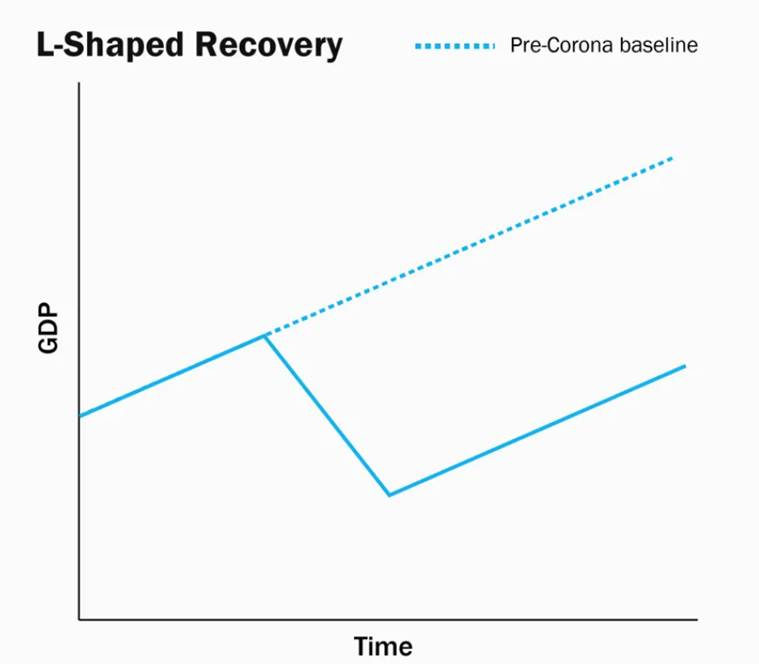

An L-shaped recovery means a permanent loss to the country’s income potential, for the baseline trajectory of growth permanently shift lower than what otherwise had been. This is probably the worst-case scenario for any country’s recovery from a recession period, and it happens if the country witnesses a permanent loss in its resources to produce. Economically, this is reflected through an inward shift in the economy’s transformation curve. As for India, it would be safe to say this really hasn’t been the case.

The very definition of these two forms of recovery states that both sides of the conversation are exaggerating the situation, making it only worse for the near future. It is because acceptance and acknowledgement are the first steps to change. Let me trace how.

If one calculates the GVA level that a V-shaped recovery would require, one finds that it is 20% more than what the actual Q1 GVA is. Again, even if GVA grows by 7% (Y-o-Y) from here on, it will take another three years just to cross the level that marks a V-shape recovery this year.

Of course, in three years’ time, both GVA and GDP would have grown much higher according to the original trend line and that is why the reality may be closer to an L-shaped recovery, which points to a permanent loss of GDP and GVA.

Of course, Covid is a global pandemic and it has left no economy unscathed. But the point of this analysis is to correct the misconception about the shape and form of the economic recovery so that the government can make smarter policy choices this time around.

For instance, if there is a consensus that India suffers from weak consumer demand (as shown by the Private Final Consumption Expenditure (or PFCE) component in the GDP data table) and that Indians across several sectors of the economy are earning much less than what they were doing in the past (as shown by the GVA data table) then the government can think in terms of either boosting its spending in such a manner that beefs up the incomes of the worst-hit or provides a tax relief — say a cut in GST rates or taxes on petroleum products — to improve the purchasing capacity of the consumers.

Before the pandemic hit, India’s economy was decelerating sharply, as shown from the over 8 per cent gross domestic product in 2016-17 to just about 4 per cent in 2019-20. The government, and the finance minister, however, explicitly declined this decline, both in the form of verbal agreement and in any probable policy action that could have been taken.

This means that if there’s no acknowledgement of what’s going wrong, there wouldn’t be any action step to change it. And well, in India’s case, this has been the bitter truth for quite a while now.

The purpose of this discussion is to shed light on the fact that both the critics and the ruling government have been advancing false portrayals of the economy, and not only would it have an effect on the policy response in the coming period, but also people’s perceptions who have a narrow understanding of these product numbers and their overall impact.

It is of utmost importance that the political parties of the country’s leave the economy separate from their political notions, for it may be one thing to win elections through competitive populism, but it would be entirely unacceptable to hurt people’s incomes in the longer run, which, however, would be the case if we continue to overpower the reality with fairytales and facts with false speeches.