In India’s Salaried Class, Covid-19 has led to the Informalization of jobs.

In India’s Salaried Class, Covid-19 has led to the formalization of jobs.

One-third of India’s salaried workers were forced to work casually or self-employed due to the pandemic. The only salaried workers who could keep their jobs were those with secure and regular positions.

In the financial year of 31 March (2021-22), India’s gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to recover to its pre-pandemic level barring a third significant wave of infections. Nevertheless, the pandemic has caused an unprecedented and long-lasting disruption in the workforce.

Millions of people lost their livelihoods, and a massive increase in poverty resulted from the first wave and its measures in 2020 (State of Working India 2021).

At both the local and national levels, several independent surveys indicate persistently low employment rates, decreased incomes, rising food insecurity, and high levels of credit card debt. In April 2021, revenues and employment remained below pre-pandemic levels when the second wave arrived, as data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy-Consumer Pyramid Household Survey (CMIE-CPHS) points out.

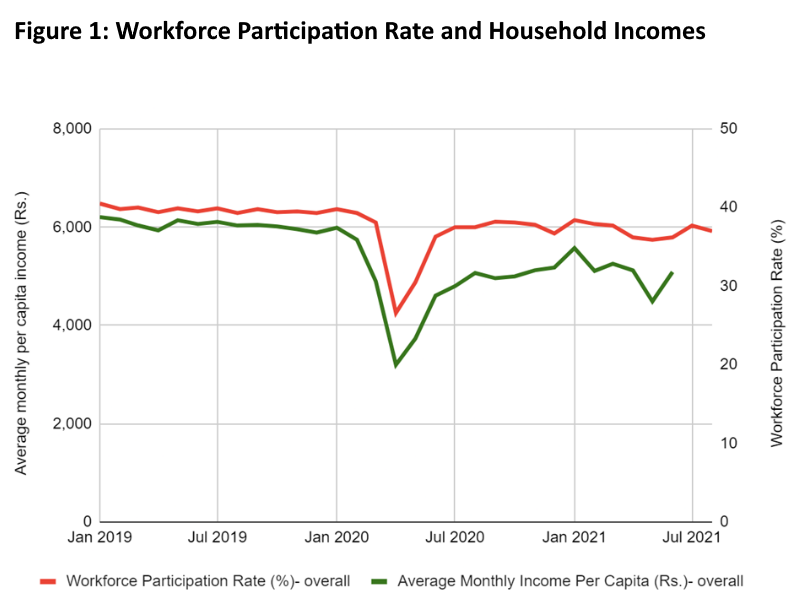

Through the middle of 2021 (after the second wave), the unemployment rate remained three percentage points lower than before the pandemic (i.e. roughly 10–12 million fewer employed people). Household incomes have not recovered either, although they are still about 80% of what they were pre-pandemic (figure 1).

An increased informality is another impact of the pandemic on the labour market. The ongoing debate over the extent to which the Indian economy is being formalised (one of the government’s core objectives) is unavoidably exacerbating the informal sector, which has grown significantly due to the sudden loss of work during the pandemic.

According to CMIE-CPHS data, the share of self-employed and casual wage workers in the total labour force increased from 78% before the pandemic to 80% in 2020-21. The Periodic Labour Force Survey also supports a rise in self-employment. Salaried workers should be able to return to their pre-pandemic work arrangements once the economy recovers. However, this isn’t a guarantee.

Even in standard times, the CMIE-CPHS data reveals a lot of movement between employment arrangements as workers move between employment situations during the pandemic. Consider the case of “permanent salaried workers,” who enjoy the highest degree of job security out of all workers. A total of 11% of the workforce was affected by the pandemic months before the outbreak.

Most of them worked in the service industries: public administration, professional services, and financial services. About 80% of permanent salaried workers remain in their current employment arrangements over a few months in a typical pre-pandemic year, while the remaining move into self-employment or out of the workforce.

This percentage drops to only 50% if we follow them for a year and a half (from the end of 2017 to the beginning of 2019). In addition to temporary salaried workers, daily wage workers also experience a high level of churn.

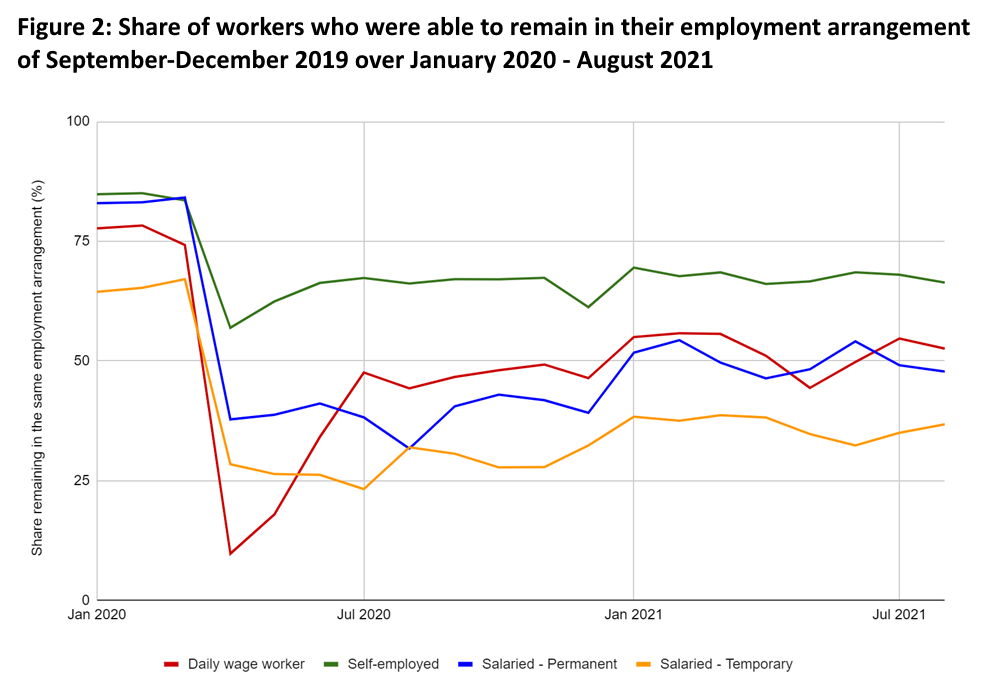

Additionally, the pandemic brought about a series of shocks. Figure 2 shows how many workers in our sample remained in their initial employment in the months following September-December 2019 (the last CPHS wave of 2019).

Salaried workers suddenly lost their jobs during the pandemic, forcing them to take on self-employment and casual wage jobs or pull out of the workforce altogether.

Only 38% of permanent and 28% of temporary salaried workers could hold on to their jobs in April 2020, as the country was in one of its most stringent lockdowns. Women and men experienced this transition differently, with nearly half of women out of work (data not shown) and only a quarter of men.

Among these salaried permanent workers, only 48% retained or returned to the same job after a year and a half. Other employees continued to work informal jobs (primarily men) or left the workforce (primarily women). The V-shaped curve shows that the daily wage workers, while initially being more negatively affected, were eventually able to return to their daily wage jobs. In a daily wage labour market, entry and exit are relatively easy due to the ease.

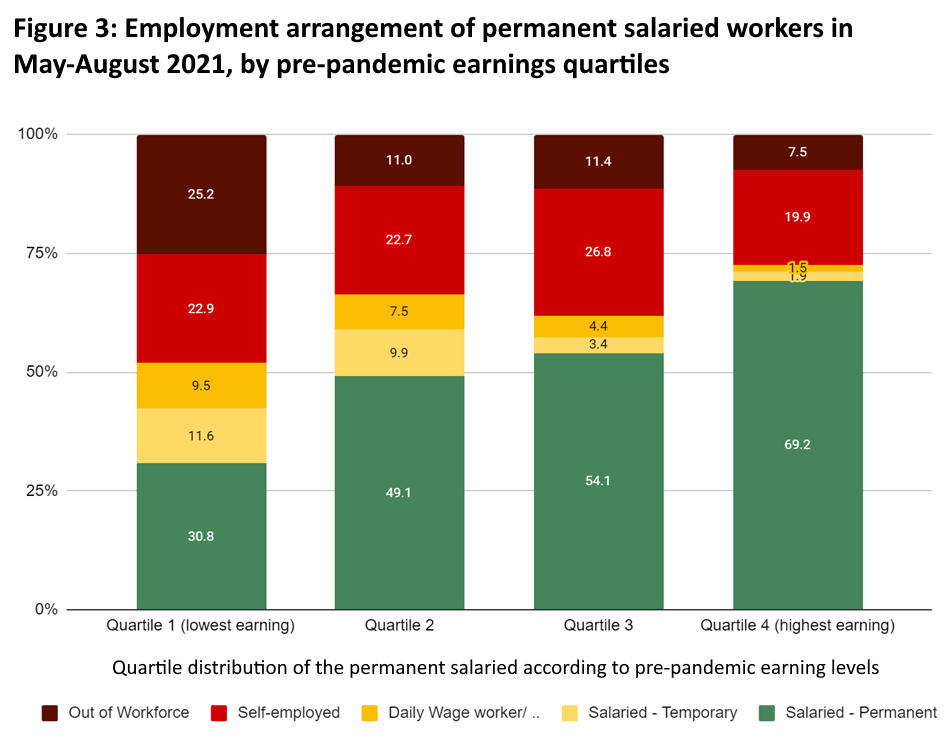

Higher-paid salaried workers had a greater likelihood of retaining their jobs, as might be expected. The earnings of permanent salaried workers from September to December 2019 are divided into four quartiles to identify high- and low-paid employees.

Among these salaried workers pre-pandemic, their employment arrangement was categorized by quartile from May to August 2021. By May–August 2021, we can determine, for example, whether the highest-paid salaried workers remain in salaried work, if they transition to another type of employment, or if they withdraw entirely from the workplace.

In India, the informal economy has been stubbornly persistent over the past decade, with a relatively slow decline in self-employment and casual wages.

Nearly a quarter of Quartile 1 employees (the lowest-paid) lost their jobs and could not find new jobs. Only three out of ten salaried workers could remain employed in the permanent sector. They were comparing this with the highest-paid employees (Quartile 4). Approximately seven in ten of these workers remained in permanent salaried jobs, and only about 8% had to leave their jobs.

There are generally two tiers of salaried or formal workers in many developing countries, including India. One level has highly secure and regular jobs with social security benefits. In contrast, the other has only the most basic salaries, often little employment security, and is usually close to informal employment. This difference is noticeable when comparing the impact of mobility restrictions and lockdowns.

While poorer salaried workers were unable to retain their jobs, higher-earning salaried workers could do so.

Younger workers have a far higher exit rate than older workers and a differential by earnings level. As seen in other industries and employment arrangements, young workers are more vulnerable to losing jobs. It is estimated that the average age of permanent salaried workers will be around 40 by 2020.

Nevertheless, by mid-2021, those remaining in permanent salaried employment had risen to 42 years old.

While India’s economy has experienced high economic growth rates over the past few decades, it has remained stubbornly informal, with the share of self-employment and casual wage work falling slower than expected. Despite structural transformation already occurring at a slower pace than ideal, it has now been reversed by the pandemic. While the number of salaried workers has declined, self-employed workers have increased.

As economic activity returns and workers resume their pre-pandemic jobs, some of the reversal is likely temporary. However, two obstacles could slow down this process significantly. Anecdotally, firms have restructured their workforce and increased automation levels.

Further, persistent softness in the labour market and low incomes suggest poor aggregate demand, which, in turn, undermines investment. When new jobs are not created in sufficient numbers, this can lock the workforce in its current state for a long time.

The relief measures implemented in 2020 prevented vulnerable households from facing the most severe consequences of the pandemic. To ensure a broad-based recovery in 2022, more must be done in the months to come.

The Indian government’s upcoming budget provides a perfect opportunity to address this problem by increasing spending, particularly for low-income households who are suffering the most from the crisis.