China Sets A Modest Growth Goal As Challenges Loom.

Three years of the "zero-COVID" policy, which put the containment of the epidemic above all other considerations, including bolstering the economy, there is now a focus on stability.

As Beijing grapples with issues in the domestic and international economies after emerging from three years of stringent COVID-19 policies, China sets its lowest growth objective in more than a quarter of a century.

Premier Li Keqiang of China announced at the beginning of the nation’s annual legislative session that the country’s gross domestic product growth target for this year is to be around 5%. This suggests that officials are less concerned about raw economic expansion as they shift their focus to other priorities.

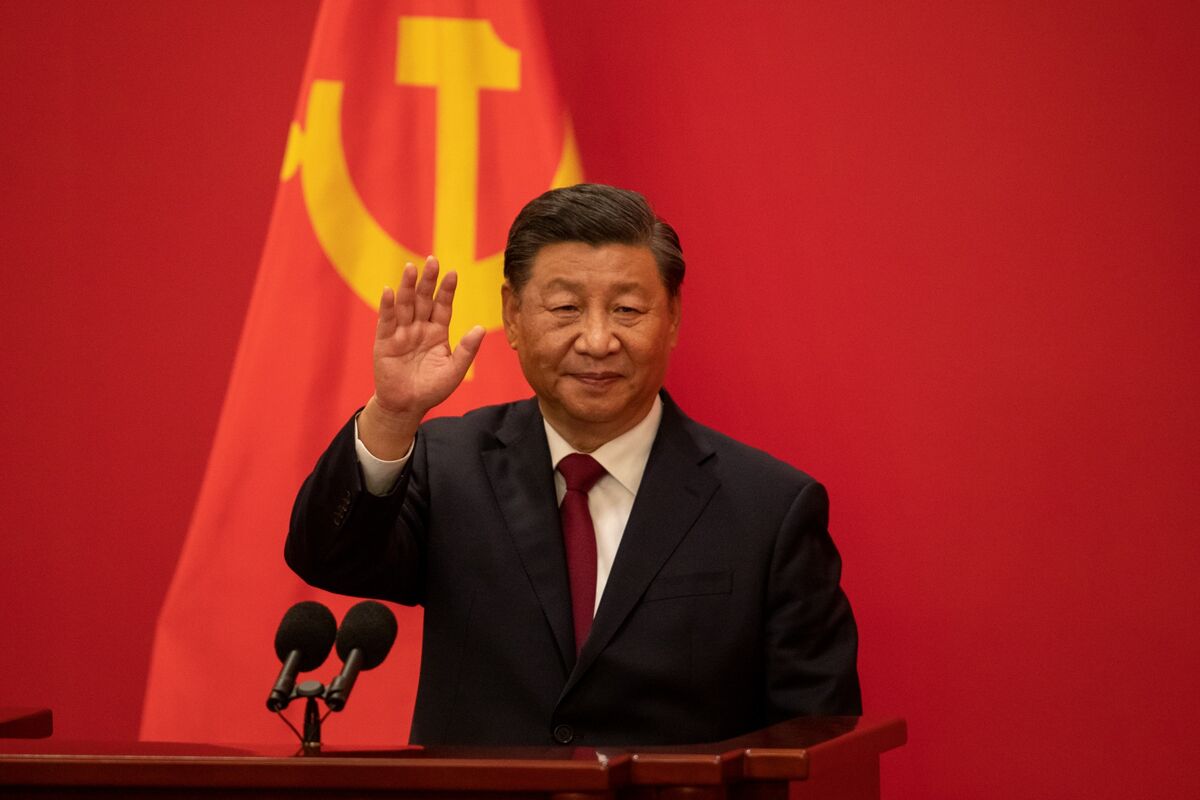

According to the reports, during this week’s legislative sessions, leader Xi Jinping is anticipated to further solidify his control over the industries of security, finance, and technology by reorganizing key positions to further reduce the government’s influence over policy-making at the expense of the Communist Party.

The growth target for this year was more cautious than the roughly 5.5% objective set by Beijing last year, which the second-largest economy in the world just missed because of Mr. Xi’s strict COVID restrictions and a protracted real estate collapse. Except for the COVID-plagued 2020, when officials completely abandoned their aim, last year’s 3% growth rate was the lowest in decades.

In his final government work report before he leaves office, Mr. Li stressed the need for prioritizing economic stability and pursuing advancement while maintaining stability. After three years of the “zero-COVID” policy, which put the containment of the epidemic above all other considerations, including bolstering the economy, there is now a focus on stability.

When the COVID-related limitations are lifted, China’s economy may be able to regain its footing, which might allow it to eventually overtake the United States as the world’s greatest economy—a potential that many analysts had grown less optimistic about as the epidemic dragged on.

If China’s economy grows at about 5% this year, its economy would increase by an average of roughly 4.6% over the following four years, which is a slight decrease from the 6.7% common annual boom price between 2015 and 2019.

The relatively conservative 5% growth target for the near term demonstrates that policymakers are wary of several obstacles that, even with COVID controls removed, could slow the pace of recovery. These obstacles include lukewarm business and consumer confidence, weak overseas demand for Chinese goods, and high local government debt loads that may limit their ability to stimulate the economy.

Given the robust recovery in corporate activity in the first two months of the year, the 5% objective is exceptionally conservative, according to Louise Loo, an economist with Oxford Economics headquartered in Singapore who specializes in China. China’s industrial, service, and construction sectors all had a significant resurgence in January and February, according to official and private indicators.

The wording used today indicates that Beijing thinks the positive effects of the reopening would probably only last a short while, Ms. Loo added. The drive from policymakers is to invest just enough to achieve the 5% growth goal.

According to Mr. Li, the government will raise fiscal spending by 5.6% this year, which is less than the rise from the previous year, while fiscal revenue is anticipated to expand by 6.7% this year, which is more than it did last year. Authorities want to have a fiscal deficit of 3% of GDP this year, up from 2.8% in 2022, which suggests Beijing won’t be actively stimulating the economy.

This year, it will be interesting to see how much export growth slows down after sustaining China’s economy for a large portion of the epidemic. When consumers and firms in the West cut down on spending amid central banks’ strong attempts to manage inflation, export growth started to drop year over year until turning around in October. China is expected to publish trade figures for the first two months. Experts’ claim that declining transportation prices and a recent overabundance of empty containers at Chinese ports indicate that trade demand is still weak.

Policymakers may need to increase monetary or fiscal easing and infrastructure spending again if exports are significantly worse than expected, Goldman Sachs economists warned clients. The longevity of any post-pandemic recovery in consumer spending is another important issue for China’s overall recovery. Although others have claimed that continued uncertainty will stifle consumers’ desire to indulge, economists are looking to see how Chinese families use their mountain of spare money amassed during the epidemic.

The government should “stabilize expenditure on big-ticket products and stimulate recovery in consumption of consumer services,” Mr. Li said, although he omitted to suggest cash transfers, a pandemic-era strategy frequently used in many Western nations to promote demand. Official statistics show that youth unemployment is still high, having reached a peak of about 20% last year. More employment instability for migrant workers results from manufacturers’ reluctance to hire due to shaky export demand.

The troubled real estate sector, which has been in a slump since late 2020, when authorities started severely enforcing credit limitations on real-estate developers, received no fresh help from officials. The government’s work report advocated for assistance for young people, recent urban migrants, and first-time homebuyers.

This implies that even while regulators are expected to offer property some respite this year, it might not get the chance to play the big role in development it once did. The general air of caution in the government work report underscores Beijing’s ongoing concern with economic responsibility, which preceded the epidemic. The fiscal sustainability issue will be given priority by Beijing this year, according to Houze Song, a fellow at the Paulson Institute in Chicago.

To that end, Beijing gave a modest signal of support for local governments on Sunday. Local governments’ debt loads grew as a result of COVID-related spending mandates and the property market downturn, which hurt the land auctions that had grown to be a significant source of income for local officials.

Compared to last year, when they increased by 18%, Beijing’s fiscal transfers to local governments are only expected to rise by 3.6% to 10.06 trillion yuan this year.

Beijing will let localities issue a total of 3.8 trillion yuan, or $550 billion, in local government special-purpose bonds, down from 4.04 trillion yuan last year. These bonds are mostly used to fund infrastructure projects.

Despite the objectives set in Sunday’s government work report, the economy’s performance will depend on whether the new cabinet, which is comprised largely of Mr. Xi’s supporters, can restore consumer and corporate confidence. Eswar Prasad, a professor of trade policy at Cornell University, stated that the difficulty the government has is how to support the private sector, which is essential for improving employment and productivity growth.

edited and proofread by nikita sharma