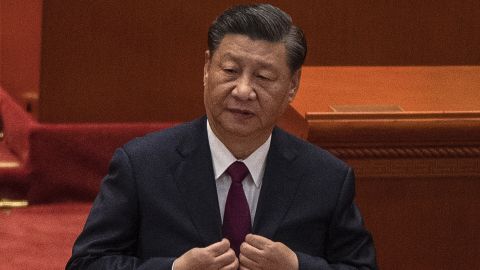

Xi worries about the Chinese economy because there are trillions at risk!

The “zero-Covid policy” and the real estate crisis, both of which have significantly impacted Beijing’s industrial units, have resulted in significant economic hardship. This is taking place as Chinese President Xi Jinping begins his third term as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Niels Graham, an assistant director at the Geo Economics Center, wrote an article for the Atlantic Council claiming that the actions he takes during his third term may force the Chinese economy to contract by up to $5 trillion over the next five years, which would negatively affect global economic growth.

Ten years ago, when he first began in his position, the economic climate was completely different from what it is today. China was newly rich and expanding quickly when Xi took office as president in 2012. Over Xi’s first two terms, the Chinese economy nearly doubled in size and grew by an average of about 7% annually.

Since then, a lot has changed in the scenario. Graham anticipated that China will miss its goal for annual GDP growth for the first time since 1989. Beijing’s official explanation for the slowdown, according to the Atlantic Council, is the extensive COVID-19 restrictions it has placed nationwide.

However, economic issues including a real estate market collapse, strained local government budgets, and a surge in youth unemployment suggest that the slowdown may have deeper reasons. Growth was also slower before the outbreak started. New research from the Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center and the Rhodium Group’s China Pathfinder examines whether the growth slowdown is a temporary blip caused by Beijing’s pandemic response or a sign that China is deviating from market thinking as concerns about the country’s economic performance increase.

The information, which spans the years 2010 to 2021 and includes information on the growth of the financial system, market competition, trade openness, steps toward a modern innovation system, direct-investment openness, and portfolio openness, shows that China’s economy has undeniably converged with open market economy norms, even though the process has been uneven.

Over the past 10 years, Beijing has focused on integrating its economy with global trade flows. It has increased the amount of global goods that flow through its economy from roughly 9% in 2010 to 12.5% in 2021 and decreased the import tariffs it imposes, from a mean tariff rate of about 10% in 2010 to 7.5% in 2021. China’s path toward trade liberalization hasn’t been as straightforward, too. Non-tariff barriers to the trade of goods, services, and digital goods, as well as Beijing’s resistance to changing exchange rates to balance its budget and subsidies, complicate the story of China’s development.

Given the expanding importance of digital commerce for advanced economies, Beijing’s limits on digital trade are particularly noteworthy. According to the Atlantic Council, China’s ranking in this category has declined since 2014 as a result of new limitations placed by Xi during the previous eight years. Near-term demand for Chinese goods overseas is declining as the rest of the world edges closer to the recession, and Graham argued that a long-term concentration on export-driven development cannot take the place of a move toward domestic spending. Beijing still has to increase domestic demand for China to switch to a sustainable economic model.

China has also chosen to look inward during the past ten years as opposed to turning away from the United States and the European Union as innovative partners. With Xi stressing the need for growing “self-reliance and strength in science and technology” during the party conference, this trend is most likely to continue. There is a chance that this could reduce China’s capacity for innovation by squeezing resources and limiting opportunities for international cooperation, according to Graham.

Despite increases in R&D spending, China continues to fall short of the average open-market economy in terms of innovation quality. For instance, when adjusted for GDP, China’s payments for the use of its intellectual property abroad only came to about one-seventh of the average amount received by open-market economies; this suggests that Chinese intellectual property is still unattractive in comparison to that of other advanced economies.

Additionally, in 2021, most aspects of China’s transition to a market economy slowed down, including innovation. Beijing’s efforts to modernize its financial system and increase its market competitiveness have stalled, and since 2020, it has started to be less welcoming to direct and portfolio investment. Given that the Politburo Standing Committee is entirely made up of party faithful for the first time since 1989, the Twentieth Party Congress showed no signs of bucking this trend. According to the Atlantic Council, this will have dangerous effects on China’s long-term growth rate.

The harm caused to China’s GDP growth prospects by the collapse of its real estate market and its adherence to its zero-COVID policies may force Beijing to resume the pro-growth reform course the CCP outlined in 2013 but largely abandoned during Xi’s second term. Unfortunately, the fear is that Beijing will instead revert to the statist solutions that have defined the economic direction of the end of Xi’s second term, which is the more likely outcome. This could result in a long-term GDP growth rate of only 2 to 3 percent, drastically lower than the 5 percent analysts had previously predicted.

The Economy Is Suffocated by Zero-COVID

The zero-COVID policy in China has strangled the nation’s economy and crushed investor and consumer confidence. Although China is now dealing with other challenges as well, I do not think a true economic comeback is feasible without giving up zero COVID. Zero-COVID has hurt domestic and international investment and increased uncertainty due to rising expenses.

China may be spending 1 billion renminbi (about $140 million) every day on regularized COVID-19 testing, according to an estimate made a few months ago by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). We calculated that 1-3 percent of China’s population—roughly 10–40 million people—were under some kind of lockdown at any one time in August.

A total of 33 cities were placed under lockdown when COVID-19 peaked in early September, putting an estimated 65 million people at risk. Even though we anticipate China’s zero-COVID policy to loosen up in 2023 thanks to a recalibration of terms and strategies, I do not see the mood of consumers and investors improving as long as the threat of lockdowns persists.

The Chinese economy may have hit its bottom in the second quarter of this year, but it has only just begun to rebound. China’s GDP is expected to grow by 3.3% in 2022, according to the EIU, which is a more optimistic forecast than others. The deteriorating real estate market is not only damaging public trust in the system, but it is also increasing local governments’ financial problems by forcing them to pay for zero-COVID expenditures while no longer being able to rely on property sales as a source of income.

The federal government’s remedies to the real estate crisis have been too fragmented or tardy to give the sector, which used to make up around 25% of GDP, new vitality. Furthermore, because real estate accounts for 70% of household wealth in China, the housing market downturn is not only slowing down economic development but also upset households.

China’s dedication to zero-COVID makes it clear that under Xi Jinping’s administrative system, politics and security take precedence over the economy. Could the president regain his sense of reason now that he is guaranteed a third term? Investors would most appreciate a return to realism and predictability in the Chinese market.

I don’t, however, hold my breath. Instead, I am keeping an eye out for changes to zero-COVID, more forceful measures to halt the property sector’s avalanche and policy assistance for the struggling private sector at the Party Congress in October. As of now, it appears more probable than not that ideologies will continue to rule policymaking, leading to less-than-ideal economic results.

Many anticipate that China’s rigorous zero-COVID policy would eventually be relaxed, resulting in economic revival. Yes, but only to a certain extent. The epidemic is only one aspect of China’s severe economic problems. Since Xi Jinping assumed office ten years ago, China’s economic development has slowed down dramatically. The economy already had problems, which the epidemic only made worse.

Since no economy can continue to develop at high, predetermined rates indefinitely, China’s slump was inevitable and overdue. The pain of 2022, meanwhile, was entirely self-inflicted. With the right messaging and flexible policy, this change to more moderate growth might be handled in a way that maintains system trust. The inability to change direction, however, may be a hint that rigidity is preventing effective administration if zero-COVID indicates the trend toward centralization under Xi. As a result, Xi loses credibility as a visionary leader who is essential to China “becoming strong” and completing its “great rejuvenation” by 2049.

Despite imminent “great hurdles,” according to Xi, China is on the threshold of rebirth. Many Chinese folks might think that times are tough already. The biggest disagreement regarding economic turnaround may be between the zero-COVID principle and practical rule.