Are chipmakers set for a massive crash after a supercharged boom?

The rockstar business of the pandemic is returning to Earth as a result of rising production and declining demand.

Graphics cards were in vogue in 2021. Cryptocurrency miners and fans of video games waited in line all night to purchase the most recent high-end product from American chipmakers Nvidia or AMD. The only hot semiconductors were by no means graphics processors. The production of everything from smartphones to cars and missiles was hampered by a severe chip shortage at a time when demand for silicon-based products of every kind was surging. According to idc, a research company, the semiconductor industry’s sales increased by a quarter to $580 billion last year. Market valuations for chipmakers increased. The largest contract manufacturer in Taiwan, TSMC, rose to the tenth-most valuable firm in the world ranking.

The traditional semiconductor cycle, which results from the gap between demand and new supply, which takes a year or two to build up, seemed to be a thing of the past with demand predicted to grow ever more ravenous, leading chip makers to invest like there was no tomorrow. TSMC invested $92 billion last year, up 73 percent from 2019, along with its two biggest rivals, the American company Intel and South Korean company Samsung, and committed an additional $210 billion over the following two years.

Now it appears that the chip cycle may have accelerated rather than being abolished. All kinds of chips appear to be unstable. Samsung announced last month that operating profit would decline this quarter after three consecutive quarters of record-breaking sales. According to reports, it may lower the cost of memory chips in the second half of 2022. American memory-chip manufacturer Micron Technology predicted third-quarter sales of $7.2 billion in June, which was a fifth below expectations. A research company called TrendForce projects a 10% decline in memory prices over the next three months.

According to one estimate, as the cryptosphere collapses and gamers spend more time in physical reality, graphics processor prices have decreased by 50% since January. The remaining months of the year are anticipated to be “a lot noisier than it was even a month ago,” in the euphemistic words of David Zinsner, chief financial officer of Intel, America’s semiconductor giant.

![]()

The share prices of global chipmakers have fallen by almost a third this year (see chart 2), about half as much as the s&p 500 index of large American companies, as the supercharged boom risks becoming a supersized bust. Geopolitical tensions also run the risk of rupturing intricate supply chains and dividing the world market. The superstar industry of the pandemic suddenly seems much less brilliant

Awesome foresight of chipmakers

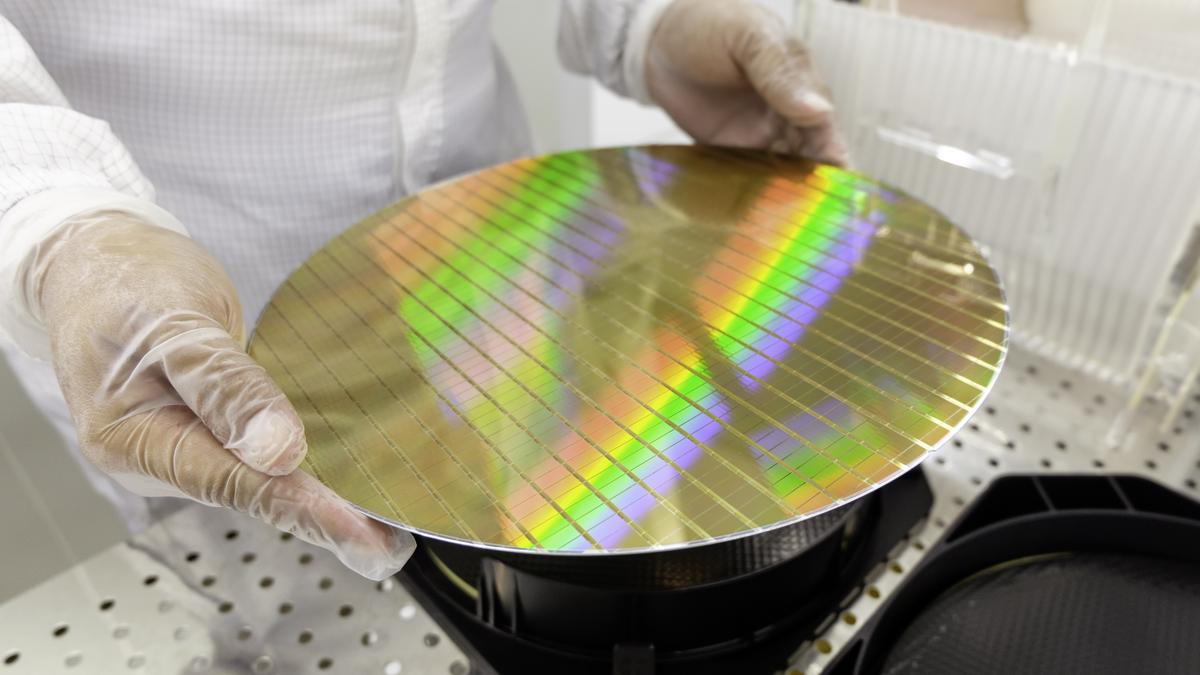

Begin with the supplies. Installing new equipment in existing fabs is one method businesses have been increasing capacity (as chip factories are known). According to Malcolm Penn of the research firm Future Horizons, global spending on machinery to etch chips into silicon wafers increased by roughly 75% in the second half of 2021 compared to pre-covid levels. Given that it takes around a year for these investments to result in new semiconductors, a production glut may occur in the latter half of 2022.

Building new fabs, which might take many years, is another approach to improving capacity. A different research organisation called semi claims that 34 of these went online in the world in 2020 and 2021. There will be 58 more that will start production between 2022 and 2024. That would increase the world’s capacity by almost 40%. Six fabs are under construction at Intel, including a $20 billion cutting-edge “megafab” in Ohio, as well as facilities in Arizona and Magdeburg, Germany. A sizable contemporary fab in Texas is among Samsung’s planned investments. A comparable one is being built in Arizona by tsmc. By 2025, the majority of these are anticipated to start generating chips.

There was always a chance that the demand might have decreased by the time any of this new supply became available. However, it seems that the desire for chips has subsided earlier than anticipated. The market for personal computers (PCs), which makes up roughly 30% of the total demand for all types of processors, is where the most obvious indications may be seen.

Global pc shipments are anticipated to decline by 8% this year, according to idc, after benefiting from the pandemic as more people started working and attending school from home. This is partially due to some of those epidemic purchases just being moved forward. Another 20% of demand, smartphone sales, are also predicted to decline. China, the largest smartphone market in the world, saw a third less smartphone shipments in April than in the same month last year. If the global economy enters a recession, the decline in sales of computers and smartphones would be even more pronounced.

About one-tenth of the world’s chips are used in data centres and the production of automobiles. This year, the demand is not expected to decline. But there are indications of softening. Data centre power source server chip orders from China have decreased.

To prevent the kind of shortages that prompted them to reduce output last year, several terrified automakers have double- or triple-ordered semiconductors. Broker Stacy Rasgon of Bernstein notes that over the past few quarters, automotive chip shipments have been around 40% more than one might anticipate given the volume of vehicles shipped and the normal amount of chips found in a single vehicle. Large semiconductor inventories in the automotive sector could lead to an abrupt drop in new orders.

Another strong influence may amplify the downward pressure on pricing. Supply and demand for semiconductors are increasingly influenced by political factors on a national and worldwide level. On the supply side, the chip crisis of last year alarmed governments all over the world and served as a reminder to people in the West that Asia is the region where 75% of all semiconductors are made.

Many people today desire to bring manufacturing within national borders, particularly for cutting-edge chips that are thought to be strategic. Congress in America is debating the chips Act, which, if passed, would give the industry up to $52 billion over five years in subsidies and grants for research and development. The EU’s plan provides more than €43 billion ($44 billion) through 2030. Similar programmes are used in India, Japan, and South Korea. China has long subsidised semiconductors and introduced a programme in 2014.

edited and proofread by nikita sharma