What are derivatives : An introduction

What are derivatives : An introduction

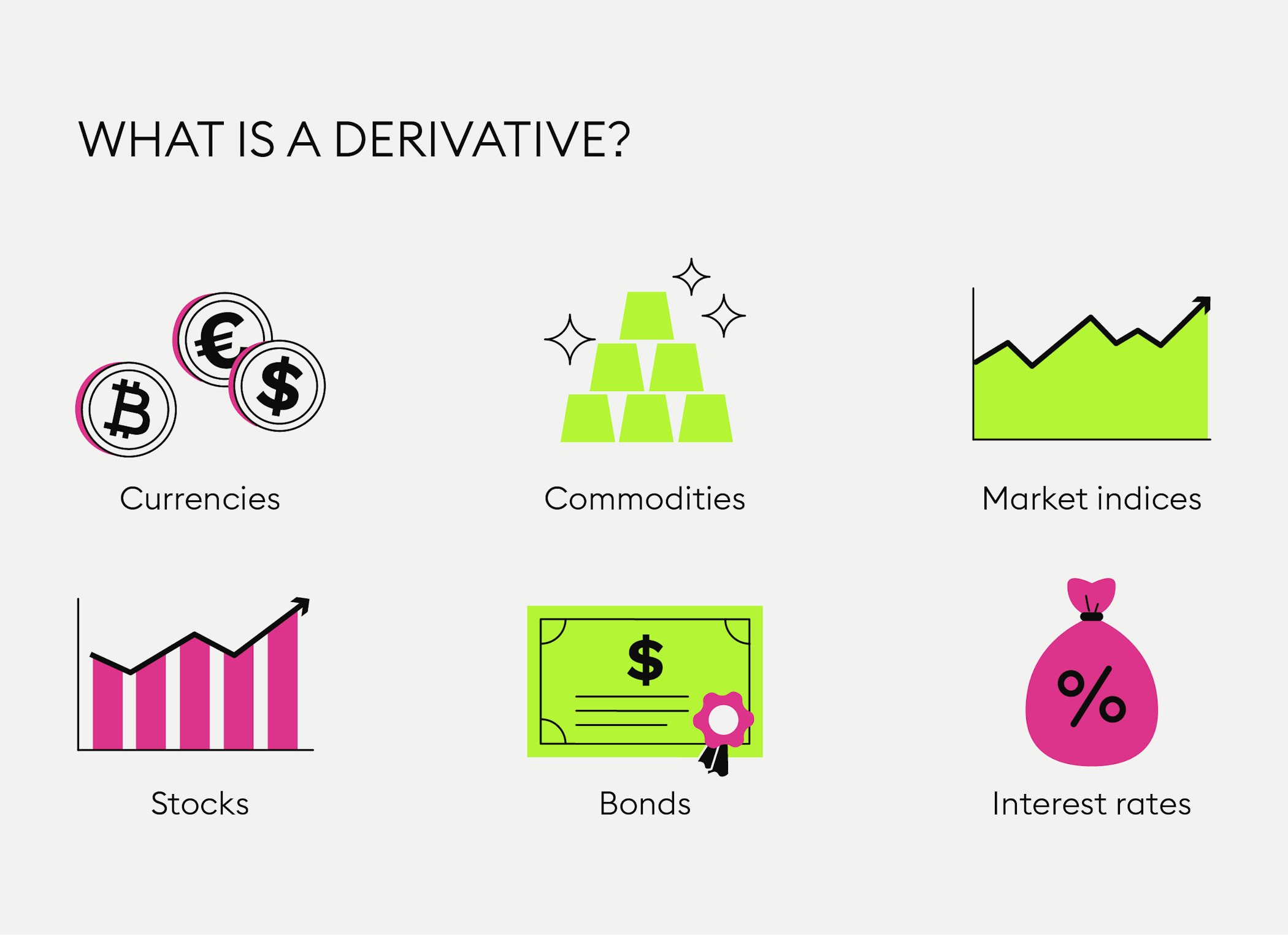

A derivative is a contract between two or more parties in which the value of the contract is determined by an agreed-upon underlying financial asset (such as a securities) or collection of assets (like an index). Bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates, market indexes, and stocks are common underlying instruments.

A derivative is a contract between two or more parties whose value is determined by an underlying financial asset, index, or security that has been agreed upon.

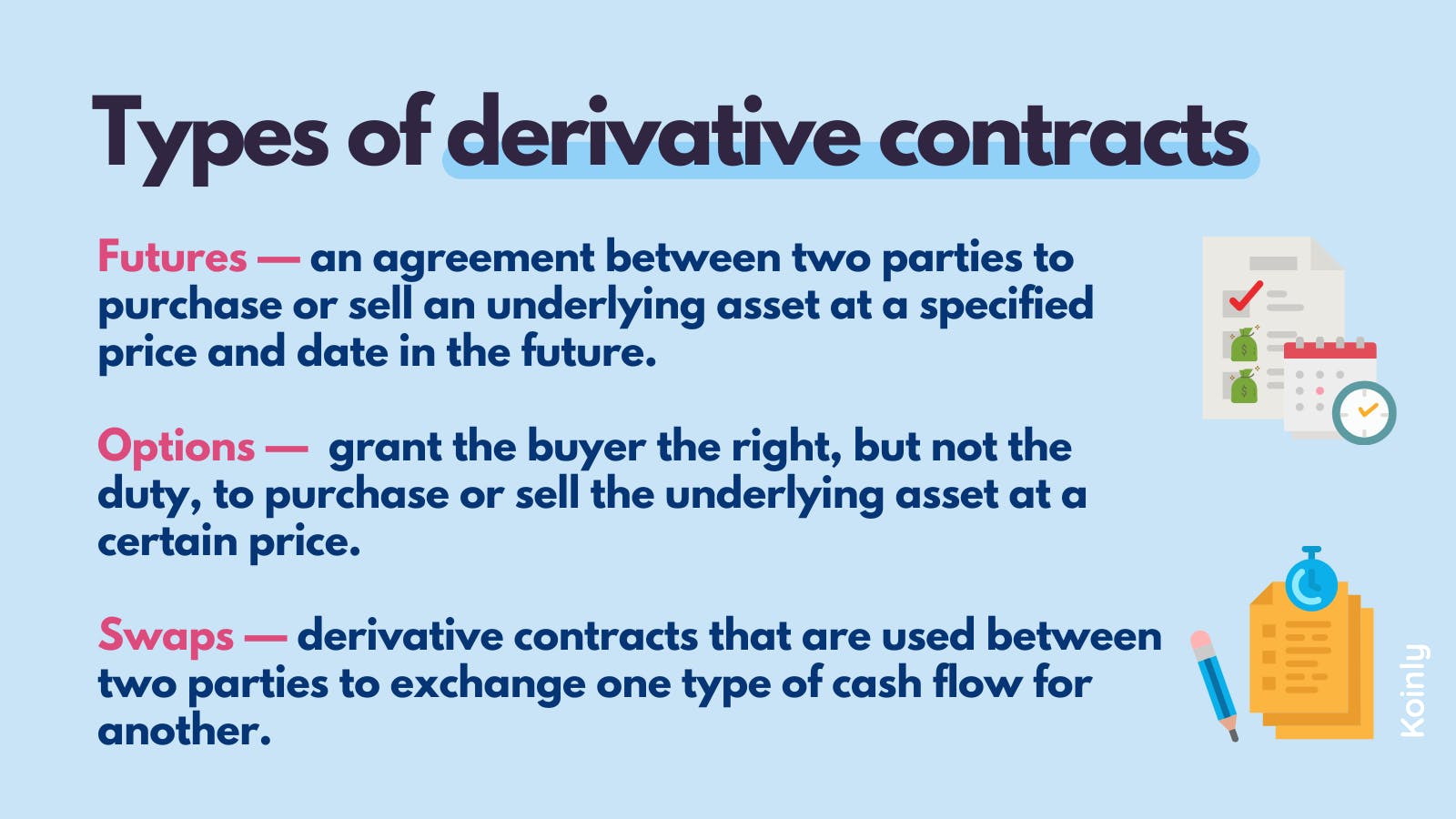

Derivatives such as futures contracts, forward contracts, options, swaps, and warrants are extensively employed.

Derivatives can be used to reduce risk (hedging) or to take on risk with the prospect of a similar payoff (speculation).

Derivatives: An Introduction

Derivatives such as futures contracts, forward contracts, options, swaps, and warrants are extensively employed.

Contracts for Futures

Because the value of a futures contract is influenced by the performance of the underlying asset, it is a derivative. A futures contract is an agreement to purchase or sell a commodity or investment at a defined price and on a future date. Specific quantity quantities and expiration dates are used to standardize futures contracts. Commodities like oil and wheat, as well as precious metals like gold and silver, may be traded using futures contracts.

Options on Stocks

Because its value is “derived” from the underlying stock, an equity or stock option is a sort of derivative. Calls and puts are two types of options. A call option offers the holder the right to purchase the underlying stock at a defined price (known as the strike price) and by a specific date specified in the contract (called the expiration date). A put option offers the holder the right to sell the stock at the contract’s specified price and date. An option premium is a one-time fee that must be paid before it may be used.

The risk-reward equation is frequently seen to be the foundation for investment philosophy, and derivatives may be used to either minimize risk (hedging) or speculate, depending on the amount of risk against reward. A trader may, for example, try to benefit from an expected reduction in the price of an index, such as the S&P 500, by selling (or “going short”) the relevant futures contract. The risks connected with the price of the underlying asset can be passed between the parties participating in the transaction via derivatives.

Exchanges and Regulations for Derivatives

The Securities and Exchange Commission regulates some derivatives that are traded on national securities markets (SEC). Other derivatives are traded over-the-counter (OTC), which involves parties negotiating separately.

Futures

The majority of derivatives are traded on stock exchanges. Commodity futures, for example, are traded on a futures exchange, which is a marketplace for the purchase and sale of numerous commodities. Members of the exchange are brokers and commercial traders who must be registered with the National Futures Association (NFA) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) (CFTC).

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) supervises futures markets and is a government organization tasked with ensuring that markets operate fairly. Preventing fraud, abusive trading methods, and regulating brokerage companies are all possible aspects of the monitoring.

Options

The Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), the world’s biggest options market, trades option contracts. The SEC regulates the members of these exchanges and monitors the markets to verify that they are operating correctly and equitably.

OTC Transactions

It’s vital to keep in mind that restrictions differ based on the goods and how it’s exchanged. Trades in the currency market, for example, are conducted over-the-counter (OTC) between brokers and banks rather than on a regulated exchange. A firm and a bank, for example, may arrange to swap one currency for another at a specified rate in the future. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates banks and brokers. Investors should be mindful of the dangers associated with OTC markets since they lack a central marketplace and the same level of regulatory monitoring as transactions conducted on a national exchange.

Derivatives between two parties

A commodity futures contract is an agreement to purchase or sell a certain amount of a commodity at a specified price on a future date. Commodity futures are frequently used to hedge or protect investors and companies against price fluctuations in commodities.

Farmers and millers, for example, employ commodities derivatives to give some “insurance.” The farmer joins the contract to lock in a reasonable price for the product, while the miller enters the contract to ensure the commodity’s supply. Although hedging has decreased risk for both the farmer and the miller, both are still vulnerable to price fluctuations.

Commodity Derivatives as an Example

While the farmer is guaranteed a certain price for the product, prices may rise (due to, for example, a scarcity caused by weather-related occurrences), and the farmer will lose any extra money that could have been received. Similarly, commodity prices may fall, forcing the miller to pay more for the commodity than he would have otherwise.

Let’s say a farmer signs a futures contract with a miller in April 2020 to sell 5,000 bushels of wheat for $4.404 a bushel in July.

The market price of wheat falls to $4.350 on the expiration date in July 2017, but the miller must buy at the contract price of $4.404, which is more than the current market price of $4.350. The miller will pay $22,020 (4.404 x 5,000) instead of $21,750 (4.350 x 5,000), but the farmer will reclaim a higher-than-market price.

The miller’s hedge, on the other hand, would have permitted the wheat to be acquired at a $4.404 contract price rather than the $5 prevailing price at the expiration date in July if the price had increased to $5 per bushel. The farmer, on the other hand, would have sold the wheat for less than the market price of $5.

Derivatives’ Advantages

Let’s look at the mechanics of different types of derivatives using the scenario of a fictional farm. Gail, the owner of Healthy Hen Farms, is concerned about recent changes in chicken pricing or market instability as a result of bird flu rumors. Gail wants to safeguard her company from another round of bad luck. As a result, she meets with an investor who invests in a futures contract.

Regardless of market price, the investor pledges to pay $30 per bird when the chickens are ready for slaughter in six months. If the price is above $30 at that time, the investor will gain since they will be able to acquire the birds for less than the market price and sell them for a profit on the market. Gail will gain if the price goes below $30 because she will be able to sell her birds for more than the current market price, or more than she would obtain on the open market.

Hedging and Derivatives

Although the phrase “hedging” may sound like something your gardening-obsessed neighbor does, it is a helpful strategy that every investor should be aware of when it comes to investing. Hedging is a means to acquire portfolio protection in the stock market, which is frequently equally as crucial as portfolio appreciation.

Hedging is frequently addressed in a more general sense than it is described. It is not, however, an obscure phrase. Even if you’re a novice investor, understanding what hedging is and how it works might be advantageous.

Gail is shielded from market price swings by engaging into a futures contract, as she has locked in a price of $30 per chick. She could lose money if the price rises to $50 per bird as a result of the mad cow concern, but she’ll be safe if the price drops to $10 as a result of reports of a bird flu breakout. Gail can concentrate on her company instead of worrying about price changes since she hedges with a futures contract.

It’s vital to keep in mind that when corporations hedge, they’re not betting on the commodity’s price. Instead, the hedge is essentially a risk management tool for each party. Each party’s profit or margin is built into their pricing, and the hedge protects those profits from being wiped out by market fluctuations in the commodity’s price. By signing into the contract with each other, both parties hedged their gains on the transaction, regardless of whether the commodity price goes higher or lower than the futures contract price by expiry.

What Is Hedging and How Does It Work?

Hedging is best understood by seeing it as a type of insurance. When people choose to hedge, they are protecting themselves against the financial consequences of a negative occurrence. This does not certain that all bad occurrences do not occur. However, if a bad event occurs and you’ve appropriately hedged your bets, the impact of the occurrence is mitigated.

Hedging is used practically everywhere in practice. When you get homeowner’s insurance, for example, you are protecting yourself against fires, break-ins, and other unanticipated tragedies.

Hedging tactics are used by portfolio managers, individual investors, and organizations to decrease their exposure to various risks. Hedging in the financial markets, on the other hand, isn’t as straightforward as paying an insurance company a yearly fee for coverage.

Hedging against investment risk is employing financial instruments or market tactics in a planned manner to mitigate the risk of adverse price changes. To put it another way, investors hedging one investment by trading in a another one.

Hedging technically entails making offsetting trades in securities with negative correlations. You will, of course, have to pay for this sort of insurance in some way.

If you hold shares of XYZ Corporation, for example, you may buy a put option to safeguard your investment from big downturns. However, you must pay a premium to obtain an option.

As a result, lowering risk always means lowering possible rewards. Hedging is, for the most part, a practice used to mitigate the risk of a prospective loss (and not maximize a potential gain). You have generally lowered your potential reward if the investment you are hedging against produces money. If, on the other hand, the investment loses money and your hedge is effective, you will have cut your losses in half.

Getting to Know Hedging

The use of financial products known as derivatives is common in hedging tactics. Options and futures are two of the most used derivatives. You may use derivatives to create trading strategies in which a loss in one investment is compensated by a gain in another.

Assume you hold Cory’s Tequila Corporation stock (ticker: CTC).

You are concerned about certain short-term losses in the tequila sector, despite your long-term belief in the firm. To hedge against a drop in CTC, you can purchase a put option on the stock, which gives you the right to sell CTC at a certain price (also called the strike price). A married put is the name for this approach. If the stock price falls below the strike price, the put option gains will compensate for the losses.

Another common hedging scenario includes a corporation that is reliant on a certain commodity. Assume that Cory’s Tequila Corporation is concerned about agave price fluctuation (the plant used to make tequila). If the price of agave skyrocketed, the corporation would be in serious danger since it would have a significant influence on profitability.

CTC can enter into a futures contract to hedge against the volatility of agave prices (or its less-regulated cousin, the forward contract). A futures contract is a sort of hedging mechanism that permits a corporation to acquire agave at a certain price at a future date. CTC may now plan without having to worry about agave prices fluctuating.

This hedging approach will pay off if the price of agave rises over the price stated in the futures contract, because CTC will save money by paying the lower price. However, even if the price falls, CTC is still bound to pay the agreed amount. As a result, it would have been preferable if they hadn’t hedged against this risk.

An investor may use options and futures contracts to hedge against almost anything, including stocks, commodities, interest rates, and currencies, because there are so many different forms of options and futures contracts.

Hedging Has Its Drawbacks

Every hedging method comes with a price tag. So, before you decide to utilize hedging, consider if the possible advantages outweigh the cost. Remember that the aim of hedging is to safeguard against losses, not to make money. It’s impossible to escape the expense of hedging, whether it’s the cost of an option or lost earnings from being on the wrong side of a futures contract.

While comparing hedging to insurance is appealing, insurance is significantly more exact. You are fully paid for your loss if you have insurance (usually minus a deductible). Portfolio hedging isn’t an exact science. It is so easy for things to go wrong. Although risk managers strive for the ideal hedge, it is extremely difficult to attain.

What Does Hedging Imply for You?

A derivative contract is never traded by the majority of investors. Most buy-and-hold investors, in fact, overlook short-term movements entirely. Hedging is pointless for these investors since they let their investments expand in tandem with the general market. So, why should you learn about hedging?

Even if you never use hedges in your personal portfolio, you should know how they operate. In some manner, many large corporations and financial firms will hedge. Oil corporations, for example, may use derivatives to protect themselves against rising oil prices. A foreign currency rate hedge might be provided by an international mutual fund. Grasp and analyzing these assets will be easier if you have a basic understanding of hedging.

A Forward Hedge is an example of a bet that is made in the future.

A wheat farmer and the wheat futures market are a typical example of hedging. In the spring, the farmer sows his seeds, and in the fall, he sells his produce. In the meanwhile, the farmer is exposed to the risk that wheat prices will be lower in the autumn than they are today. While the farmer wants to maximize the profit from his harvest, he does not want to bet on the price of wheat. As a result, he may sell a six-month futures contract at the present price of $40 per bushel when he plants his wheat. A forward hedge is what this is called.

Assume that six months have passed and the farmer is ready to harvest his wheat and sell it at the current market price. Indeed, the market price has decreased to about $32 per bushel. That is the price at which he sells his wheat. Simultaneously, he buys back his short futures contract for $32, netting a $8 profit. As a result, he sells his wheat for $32 plus a $8 hedging profit, for a total of $40. When he planted his crop, he effectively locked in the $40 price.

Assume the price of wheat has now increased to $44 per bushel. The farmer sells his wheat at market price and repurchases his short futures at a loss of $4. As a result, his net revenues are $44 – $4 = $40. The farmer’s losses, as well as his earnings, have been kept to a minimum.

How Does a Protective Put Protect Against Losses?

Buying a downside put option is what a protective put is (i.e., one with a lower strike price than the current market price of the underlying asset). Before the put expires, you have the option (but not the responsibility) to sell the underlying stock at the strike price. So, if you hold $100 worth of XYZ stock and want to protect yourself against a 10% loss, you may purchase the 90-strike put. This manner, even if the price drops to $50, you can still sell your XYZ shares for $90.

When Hedging Options Trades, How Is Delta Used?

Delta is a risk metric used in options trading that informs you how much the option’s price (also known as the premium) will change if the underlying securities moves $1. If you buy a 30 delta call option, the price will change by $0.30 if the underlying moves by $1.00. To become delta neutral, you might sell 30 shares (each stock options contract is worth 100 shares) to hedge this directional risk. As a result, delta may also be thought of as an option’s hedging ratio.

What Does It Mean to Be a Commercial Hedger?

A commercial hedger is a corporation or product manufacturer who utilizes derivatives markets to hedge their market exposure to the products they produce or the inputs needed to make those items. Kellogg’s, for example, employs maize in its morning cereals. As a result, it may purchase corn futures as a hedge against rising corn prices. A maize farmer, for example, would trade corn futures instead to protect himself from a market price drop before harvest.

What Is De-Hedging and How Does It Work?

The term “de-hedge” refers to the act of closing out an existing hedge position. This can be done if the hedge is no longer required, if the hedge’s cost is too high, or if the greater risk of an unhedged position is desired.

risk is an important, yet perilous, aspect of investment. Having a fundamental understanding of hedging methods will lead to a greater understanding of how investors and firms strive to protect themselves, regardless of the type of investor one aspires to be.

Whether or whether you opt to start practicing the complex applications of derivatives, understanding how hedging works will help you improve your market knowledge, which will always help you be a better investor.

Derivative Swap

Interest-rate products can also benefit from derivatives. The most common application of interest rate derivatives is to protect against interest rate risk. Interest rate risk occurs when the price of the underlying asset changes due to a change in interest rates.

Loans, for example, can be offered as fixed-rate loans (with the same interest rate throughout the loan’s life), or variable-rate loans (with the rate fluctuating dependent on market interest rates). Some businesses may choose to convert their variable-rate loans to fixed-rate loans.

For example, if a corporation has a particularly low rate, it may seek to lock it in to protect itself against future rate increases. Other businesses may have debt with a high fixed rate compared to the current market and seek to exchange or swap that fixed rate for the current market’s lower variable rate. An interest-rate swap is a transaction in which two parties exchange payments so that one obtains the variable rate and the other receives the fixed rate.

Interest Rate Swap Example

Let’s say Gail has decided that it’s time to take Healthy Hen Farms to the next level, continuing our Healthy Hen Farms example. She has already purchased all of the smaller farms in the area and plans to construct a processing factory of her own. She attempts to acquire additional money, but Lenny, the lender, turns her down.

Gail financed her takeovers of the other farms with a large variable-rate loan, and Lenny is concerned that if interest rates increase, she may be unable to pay her bills. He informs Gail that he will only lend to her if she can have the loan converted to a fixed-rate loan. Her other lenders, however, refuse to adjust her present loan conditions since they expect interest rates to rise as well.

When Gail meets Sam, the owner of a restaurant chain, she receives a lucky break. Sam has a fixed-rate loan of roughly the same amount as Gail’s, which he wishes to convert to a variable-rate credit in the hopes of lower interest rates in the future.

Sam’s lenders will not adjust the loan conditions for similar reasons. Gail and Sam come to an agreement to exchange loans. They come to an agreement where Gail’s payments will go toward Sam’s loan and Sam’s payments will go toward Gail’s loan. Despite the fact that the loans’ names haven’t changed, their contract permits them to receive the loan they desire.

The deal is dangerous for both of them since if one of them fails or goes bankrupt, the other would be re-instated in their prior debt, which may necessitate payment for which Gail or Sam are unprepared. It does, however, allow them to tailor their loans to their own need.

Derivatives of Credit

A credit derivative is a two-party contract that allows a creditor or lender to shift the risk of default to a third party. The credit risk of the borrower not repaying the loan is transferred through the contract. The loan is kept on the lender’s records, but the risk is passed on to someone else. Credit derivatives are used by lenders, such as banks, to remove or lessen the risk of loan defaults from their entire loan portfolio in return for a premium.

Credit Derivatives as an Example

Gail’s banker, Lenny, agrees to provide the additional funds at a low interest rate, and Gail is pleased. Lenny is thrilled as well since his money is earning interest, but he is concerned that Sam or Gail would fail in their endeavors.

To make matters worse, Lenny’s pal Dale approaches him, requesting funds to launch his own production firm. Lenny realizes Dale has a lot of collateral and that the loan would have a higher interest rate due to the more risky nature of the movie industry, so he’s blaming himself for lending Gail all of his money.

Derivatives, fortunately for Lenny, provide another option. Gail’s debt is turned into a credit derivative, which Lenny sells to a trader at a discount to its real worth. Despite the fact that Lenny does not receive the whole amount of the loan, he receives his capital and can re-lend it to his friend Dale. Lenny is so fond of this arrangement that he keeps spinning out his loans as credit derivatives, accepting small profits in exchange for lower risk of default and more liquidity.

Contracts with Options

Healthy Hen Farms is now America’s largest poultry producer and a publicly listed firm (HEN). Both Gail and Sam are looking forward to their retirement years.

Sam purchased a large number of HEN shares throughout the years. In fact, he has put more than $100,000 into the business. Sam is becoming concerned that another shock, such as a new epidemic of avian flu, may wipe away a significant portion of his retirement savings. Sam begins seeking for someone to take on the danger for him. Lenny, who is now a seasoned investor and active writer or seller of options, agrees to assist him.

Sam pays Lenny a fee–or premium–in exchange for the right (but not the responsibility) to sell Lenny the HEN shares in a year at their present price of $25 a share. Lenny safeguards Sam from losing his retirement money if the stock market falls.

Until Sam and Gail have both taken their money out for retirement, Healthy Hen Farms stays steady. Lenny makes money from the fees and his burgeoning business as a banker. Lenny is OK since he has been collecting the payments and is confident in his ability to manage the risk.

This story demonstrates how derivatives may shift risk (and the associated benefits) from risk-averse to risk-seeking individuals. Although Warren Buffett sometimes referred to derivatives as “financial weapons of mass devastation,” they may be extremely valuable instruments when utilized correctly.

Derivatives, like all other financial products, have advantages and disadvantages, but they also have the potential to improve the general operation of the financial system.