The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Efforts to Make the Global Covid-19 Death Toll Public, Have Stopped in India

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Efforts to Make the Global Covid-19 Death Toll Public, Have Stopped in India

The organization thinks that 15 million people died due to the epidemic, significantly more than previous estimates, but has yet to reveal those figures.

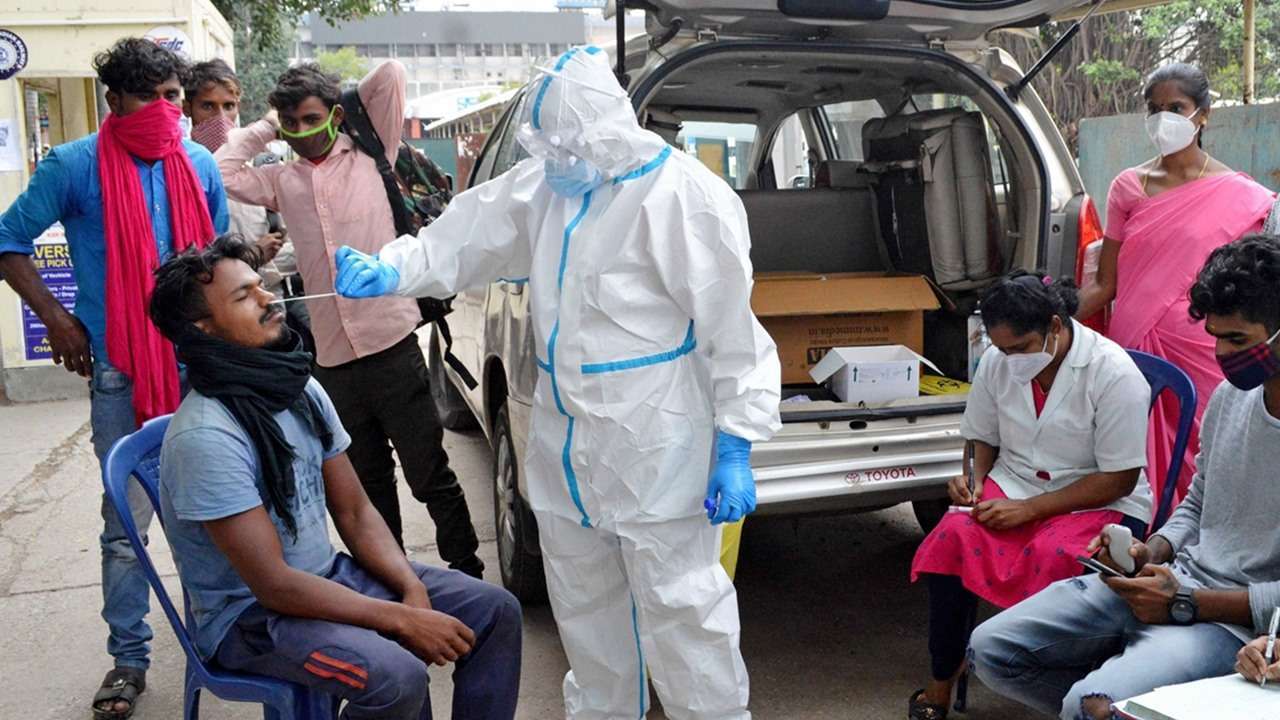

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) ambitious effort to assess the worldwide death toll from the coronavirus pandemic discovered that many more people perished than previously thought – roughly 15 million by the end of 2021, more than double the official tally of six million recorded by individual governments.

However, the staggering estimate — the result of more than a year of research and analysis by experts from around the world and the most comprehensive look at the pandemic’s lethality to date — has been delayed for months due to objections from India, which disputes the calculation of how many of its citizens died and has attempted to keep it from becoming public.

More than a third of the additional nine million fatalities are thought to have happened in India, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration has stuck to its estimate of 520,000 deaths.

According to persons familiar with the figures who were not permitted to speak publicly, the W.H.O. will reveal that India’s death toll is at least four million, making it the world’s largest.

The World Health Organization’s computation incorporated national data on reported fatalities with new data from localities and household surveys and statistical models to account for overlooked deaths. The majority of the discrepancy in the new worldwide estimate is due to previously uncounted deaths caused directly by Covid; the latest figure also includes indirect deaths, such as those caused by individuals being unable to get care for other illnesses due to the epidemic.

The delay is noteworthy because worldwide data is critical for understanding how the epidemic unfolded and what efforts may be taken to prevent a similar calamity in the future. It has wreaked havoc on the generally orderly world of health statistics, sparking a conflict at the United Nations Statistical Commission. This international agency collects health data sparked by India’s unwillingness to comply.

“It’s critical for global accounting and the moral commitment to people who have passed away, but it’s also critical practicality.” If there are subsequent waves, “understanding the death total is critical to determining whether vaccination campaigns are effective,” said Dr Prabhat Jha, director of the Centre for Global Health Research in Toronto and a member of the expert working group that supports the World Health Organization’s excess death calculation. “It’s also crucial for accountability.”

The World Health Organization gathered a team of experts, including demographers, public health experts, statisticians, and data scientists, to determine the pandemic’s impact.

As it is called, the Technical Advisory Group has been coordinating across nations to try to piece together the most comprehensive list of pandemic fatalities.

More than ten persons familiar with the data talked with The New York Times. The World Health Organization had planned to disclose the figures in January but repeatedly postponed it.

According to three persons acquainted with the situation, a few group members recently informed the World Health Body that if the organization did not reveal the statistics, the experts would do it themselves.

“We plan to publish in April,” a W.H.O. official, Amna Smailbegovic, told Inventiva.

The data distribution has been “somewhat delayed,” according to Dr Samira Asma, the World Health Organization’s assistant director-general for data, analytics, and delivery for impact, helping to oversee the computation. “We wanted to make sure everyone is consulted,” she added.

India claims that the World Health Organization’s approach is incorrect. In a statement to the United Nations Statistical Commission in February, the government declared, “India thinks that the process was not collaborative nor appropriately representative.” It also said that the process lacked “scientific rigor and reasonable examination as one would expect from an organization of the World Health Organization’s standing.”

Requests for feedback to the Ministry of Health in New Delhi were not returned.

India isn’t alone in undercounting pandemic deaths: The latest World Health Organization figures show undercounting in other major nations like Indonesia and Egypt.

According to Dr Asma, many countries have struggled to measure the pandemic’s impact precisely. “I think it is tough when you look behind the hood,” she added, even in the most modern countries. She said considerable differences in how rapidly various U.S. states reported fatalities at the outset of the epidemic, and some were still collecting data through fax.

She explained that India sent a vast team to assess the W.H.O. data analysis, which the agency was happy to have since it wanted the model to be as open as possible.

Experts worldwide have praised India’s immunization work, but its public health reaction to Covid has been criticized for being overconfident. In January 2021, Mr Modi declared that India had “saved mankind from a major tragedy.” A few months later, his health minister announced that the country was “in the latter stages of Covid-19.” As a result of this complacency, administrators made mistakes and attempted to muzzle critical voices inside elite institutions.

Then, in April 2021, the second wave of devastation struck. Patients had to be turned away from hospitals, and oxygen was scarce. However, many fatalities remained unnoticed.

Throughout the epidemic, Science in India has been more politicized. In February, India’s junior health minister slammed research published in the journal Science that assessed the country’s Covid death toll to be seven to eight times higher than the official figure. The government questioned the methodology of research published in The Lancet in March that put India’s death toll at four million people.

“I’ve always believed that science should be met with science,” said Bhramar Mukherjee, a biostatistician at the University of Michigan School of Public Health who has been reviewing the data with the World Health Organization. “You should merely offer an alternate estimate based on robust research if you have one.” “You can’t just declare, ‘I’m not going to accept that,'” says the author.

The World Health Organization has not received India’s total mortality data for two years. Still, researchers have used data from at least 12 states, including Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Karnataka, which show at least five to six times as many deaths due to Covid-19, according to experts.

According to Jon Wakefield, a professor of statistics and biostatistics at the University of Washington, a preliminary presentation of the W.H.O. worldwide data was available in December. He played a crucial role in developing the model used for the estimations.

“However, India was dissatisfied with the estimations. So we’ve gone beyond in terms of outstanding checks and doing as much as possible given the available data, and the paper’s a lot better because of this wait,” Dr Wakefield said. “And now we’re all set to go.”

The figures show “excess mortality,” or the difference between all fatalities and those that would have occurred under normal circumstances, as defined by statisticians and experts.

The World Health Organization’s estimations include fatalities caused directly by Covid, deaths caused by Covid-related diseases, and deaths of those who did not have Covid but needed unavailable care due to the epidemic. Expected deaths that did not occur due to Covid limitations, such as those caused by road accidents, are also factored into the estimates.

Calculating global excess fatalities is a problematic endeavour. Some nations have kept meticulous records of death rates and swiftly reported them to the World Health Organization. Others have only provided limited data, forcing the agency to rely on modelling to complete the picture.

Then there are the nations that do not collect death data, notably virtually all of those in Sub-Saharan Africa, and for which statisticians must depend only on modelling.

According to Dr Asma of the World Health Organization, nine out of ten fatalities in Africa and six out of ten worldwide remain unrecorded. More than half of the world’s countries do not gather valid reasons for death. According to her, even the beginning point for this type of study is a “guesstimate.” “We have to admit we don’t know what we don’t know and be humble about it.”

The experts in the advisory group used statistical models. They made predictions based on country-specific information such as containment measures, historical rates of disease, temperature, and demographics to assemble national figures and, from there, regional and global estimates for countries with partial or no death data.

Aside from India, there are several other significant countries with inconclusive statistics.

By the end of 2021, Russia’s health ministry had documented 300,000 Covid fatalities, which the government notified the World Health Organization.

However, the Russian national statistics office, which is independent of the government, discovered an excess mortality rate of more than one million people. This figure is similar to that in the W.H.O. draft. Russia has protested that figure, but members of the organization claim it has not attempted to prevent the data from being released.

China, where the pandemic started, does not publish mortality data, and some experts have expressed concerns about underreporting fatalities, particularly early in the outbreak. The virus has claimed the lives of less than 5,000 people in China.

While China has maintained caseloads lower than most nations, it has done so by enforcing some of the world’s toughest curfews, which have had their public health consequences. A group of government experts performed one of the only studies to evaluate China’s excess mortality using internal data, finding that heart disease and diabetes fatalities increased in Wuhan during the city’s two-month lockdown. The experts believe the rise is due to people’s incapacity or unwillingness to seek care in hospitals. In the first quarter of 2020, they found that the total death rate in Wuhan was nearly 50% higher than projected.

The Modi government’s attempt to delay the distribution of the study demonstrates that pandemic data is a sensitive matter for them. “It’s an unusual approach,” said Anand Krishnan, a community medicine professor at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi, who has also been reviewing the data with the World Health Organization. “I can’t recall a moment when it has done so before.”

When the numbers reveal substantial excess fatalities, Ariel Karlinsky, an Israeli economist who established and maintained the World Mortality Dataset and worked with the World Health Organization on the figures, said they are difficult for governments to deal with. “I believe it is very reasonable for those in positions of authority to be concerned about these repercussions.”