Healthcare cannot be improved by top-down approaches

Healthcare cannot be improved by top-down approaches

Programs designed by governments for indigenous populations that fail to involve local communities and listen to them will not succeed in improving wellbeing.

A tribe of Muduaga, Kurumba, and Irula live in Attapadi, India’s first designated tribal area located near the Silent Valley National Park in Kerala’s Palakkad district. In 2013, reports of high infant mortality among the indigenous people of Attapadi shook the Kerala model of good health at a low cost. Both the state and the centre responded quickly. As an emissary of the prime minister, Jairam Ramesh, then minister for rural development, visited Attapadi in 2013 to assess the situation and implement relief measures.

The city of Attapadi has always witnessed high-profile visits by politicians and officials from the centre when there has been a spike in infant mortality, who visit tribal hamlets, hold meetings with local officials, and announce corrective measures.

The indigenous communities in Attapadi have taken several steps to improve their quality of life and prevent infant deaths. Some of these steps include the following.

- They enhance facilities, appoint more staff, and grant free treatment to all residents. Muduga, Kurumba, and Irula pregnant women in Attapadi have also been offered a particular scheme.

- By establishing community kitchens, nutrition rehabilitation centres, and a Millet Village program, malnutrition can be addressed.

- It is setting up mechanisms to expedite the process of reclaiming indigenous lands that have been alienated.

To ensure that funding does not pose a barrier to improving Indigenous health and wellbeing, special financial packages have been launched. A unique mechanism has also been set up under the sub-collector of Ottapalam to address the lack of effective inter-sectoral coordination as a critical bottleneck of ineffective governance.

Attapadi’s healthcare system

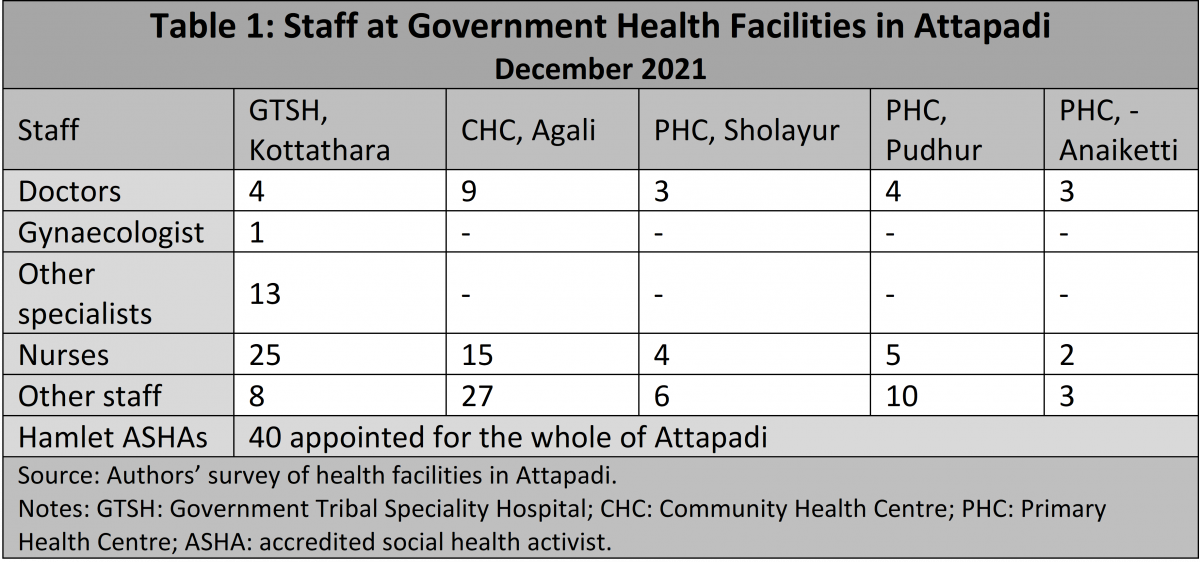

Attapadi is well-equipped with a vast network of medical facilities with doctors, specialists, and other health specialists on-hand (Table 1). A special allowance of 20% is given to all health personnel who choose to work in Attapadi. Additionally, the Integrated Tribal Development Programme (ITDP) operates two outpatient clinics and a few private hospitals in Attapadi. The EMS Cooperative Hospital in Perinthalmanna provides super-specialist care to those in need. Healthcare is provided at no cost to all patients, whether they are inpatients or outpatients.

Despite the impressive health infrastructure, personnel, and resources in Attapadi, infant mortality remains high.

In 2013, the state government launched the Janani Janmaraksha Scheme, which offered pregnant women Rs 1,000 a month after completing all antenatal care (ANC) check-ups and delivering at a hospital for 18 months. A month’s allowance of Rs 2,000 was increased in 2018. Attapadi continues to experience high levels of infant mortality despite impressive healthcare infrastructure, personnel, and resources.

In 2021, the alarm will ring.

In November 2021, four consecutive infant deaths brought Attapadi back into the spotlight. The ministry of health and tribal welfare in Kerala sent several officials and ministers to Attapadi to study the situation and announce measures to help reduce infant mortality rates. Attapadi’s government tribal speciality hospital (GTSH) will open a neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) in Kottathara, Attapadi, as one of the first announcements by the minister of tribal welfare.

We also changed the referral hospital to Government Medical College Hospital, Palakkad, from EMS Cooperative Hospital, Perinthalmanna. In December 2021, prominent politicians from the Opposition in the state visited Attapadi and called for the implementation of special measures in the area. However, so many of the programs launched since 2013 have not had the desired effect in Attapadi, has not been adequately evaluated.

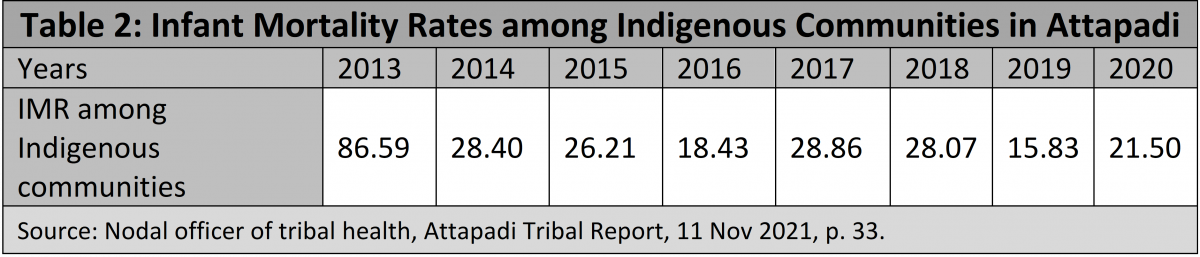

Despite all government programs (Table 2), the infant mortality rate in Attapadi has not significantly improved over time, and the data does not include stillbirths among indigenous communities.

Services centralized

The GTSH in Kottathara provided healthcare in Attapadi until now. A couple of gynaecologists who worked in this hospital were also providing antenatal care. In remote villages, this meant several hours of hiking through forests and hills before they could reach a place from where they could take a jeep or bus to Kottathara. It would take a pregnant woman between eight and more than a day to get one way, depending on the season, her health, and transportation. The village chief, Kurumba Moopan, said,

“Previously, it was a source of joy for a family when a woman became pregnant. Nowadays, it causes stress. The family must visit Kottathara hospital for ANCs on a monthly basis. It’s your responsibility. People will come asking why we did not follow the schedule if we don’t go.”

This approach had the advantages of detecting high-risk cases early and thus preventing infant mortality by screening all pregnant women.

Nonetheless, this approach has not been successful as expected based on the results. No attempt has been made to decentralize healthcare through the use of medical personnel and doctors in the various health facilities in Attapadi.

Discrimination, stigma, and force

Indigenous communities have received most interventions in a paternalistic manner. It has never been the state’s priority to engage them in problems and get their consent for different programs. For years, it has been established that the Kottathara hospital performs institutional deliveries of babies. The antenatal period has been used to gain the trust of women who don’t want to leave their homes and villages rather than listening to their concerns and building a rapport.

Health workers accompanying police officers to villages to ensure pregnant women get to the hospital in time to deliver their babies is not helping to build public trust in the system. The poor women have been stigmatized countless times for not knowing how to breastfeed their infants, thus harming them without any justification.

As if this weren’t ironic enough, a Channar revolt against the right for lower-caste women to cover their breasts happened in the 19th century.

Among the signs was the installation of a statue in the courtyard of the Kottathara hospital depicting a mother nursing her infant. The topless figure of the woman in Attapadi was noted by several young indigenous people there. Statues depicting mothers helping their children are shared throughout Kerala; unlike the figure in Attapadi, those at other hospitals show the mothers fully clothed.

Ayyankali, a social reformer who supported Channar’s revolt for the right of lower-caste women to cover their breasts, was also involved in the Channar revolt during the 19th century, making the irony worse. In the words of Idi, an indigenous youngster, Your travels have brought you to remote villages. Are there any topless women in our towns? I don’t think so. If there aren’t any topless women in our villages, how can they make such an exciting statue? As savages who roam the forests and wear no clothes, this shows how outsiders perceive us.”

Implementing a top-down strategy

The Millet Village Scheme set up in 2017 to rejuvenate traditional agriculture in Attapadi was another example of the top-down approach not leveraging the strengths of the indigenous communities. As part of Attapadi’s indigenous village council, each indigenous village has a traditional official called the mannukaran, or man of the soil. Mannukarans had the responsibility to understand the seasons, the nature of the ground where the crop was to be grown, and determine when to sow the crop.

It was, however, implemented without any input from village chiefs, mannukarans, or village assembly members. Several villages in Attapadi were drafted into this scheme in the belief that millets would solve the malnutrition problem. It has been reported that this scheme was used in several cases at the wrong time of year or in challenging to irrigate areas. In any case, the officials listed the targets that the program must achieve.

Alienation of land

Attapadi’s indigenous populations recognize that the restoration of traditional lands is of utmost importance to their wellbeing. Everyone, from experts to political parties, discusses this issue in great detail whenever there is a crisis there. Outsiders, with the connivance of local officials, have alienated land since the 1950s by producing documents proving they were the legal owners.

On the banks of the Bhavani and Siruvani rivers in Attapadi, most of the fertile land belongs to non-indigenous people today. To date, little progress has been made with regards to identifying and returning alienated traditional lands. You can find the contact information of agents offering several acres for sale by simply doing a search on the internet for land in Attapadi. In Attapadi, non-indigenous people are still subject to strict requirements and limitations when they wish to buy a piece of land, showing how the system is still broken and loaded in favour of the powerful.

A person’s land provides them with a link to their ancestors, culture, and rituals and is not simply an asset to be owned by an individual.

An integral part of the identity of indigenous people is their connection to ancestral lands. People do not own land as an asset; instead, the land provides them with a reference to their ancestors, culture, and rituals. It is a collective possession intended to benefit everyone in the community. As a result, the ancestral land in Attapadi symbolizes the umbilical cord connecting the indigenous communities to the earth as well as their culture.

Lands in Kerala have been returned to the original indigenous owners in an inequitable manner for many years. In 1986, in order to ensure the restoration of tribal lands alienated after 1960 in the state, the Tribal Land Act was passed. However, it did not take effect. It was amended in 1996, so only the sale of indigenous lands after 1968 was illegal. Many applications for the restoration of land have been stuck for years in legal red tape, which has further impoverished indigenous claimants, who have spent time and money getting their claims verified by different government agencies.

The state government stated that fear of large-scale violence between the indigenous communities and the settlers was one of the reasons they did not implement the 1986 Act and later amended it. The fact that the alienation of land is a form of institutional, cultural, and structural violence against the most marginalized has conveniently been overlooked.

Attapadi’s current population of indigenous and non-indigenous people may also be indicative of a lack of political will to carry out land reforms. In Attapadi today, most of the residents are not native to the area, according to the last census. The non-indigenous cannot accept any drastic measures such as returning all land that is rightfully theirs, which would mean losing their votes. Likewise, there is a dividing line between the indigenous communities in Attapadi, and alienating the non-indigenous communities is unwise in terms of politics and electoral.

Examples of successful marketing

Many interventions have been implemented in different parts of India to address the issue of poor health among indigenous communities. A little south of Attapadi, more than a hundred Malavasi women, are trained as health workers at the Tribal Health Initiative (THI) in Sittilingi in Dharmapuri district of Tamil Nadu.

Attapadi continues to emphasize centralized specialist care, despite these logical examples not being studied or taken seriously.

Instead of its founders or doctors, we were shown how the THI dealt with the high infant mortality rates by an indigenous community health worker. Furthermore, she mentioned how health should not be confined to a hospital and that an agricultural initiative began to address nutrition as well as livelihood issues, which are equally important. There are several initiatives across India that have successfully addressed the nutritional status of mothers and children using participatory community-based mechanisms. Attapadi, which continues to focus on centralized specialist care, has not studied or taken these sensible examples into account.

Conclusion

In terms of social justice and development, Kerala has made several firsts. As Kerala brands itself as “God’s own country,” the state and its institutions are incapable of achieving the same in Attapadi. Engaging indigenous communities and their institutions as first among equals are one of the first steps that the state government should take.

No matter what the issue is, whether it is malnourishment or antenatal care, experts and officials need to recognize listening to indigenous communities, integrating their perspectives and working with them as allies are essential first steps to making these programmes effective. Developing solutions with indigenous communities in mind should be based on their cultures and traditions in order to create inclusive development possible.

When this fails to be done, several initiatives will underperform, and in the process, valuable resources will be wasted, and even worse, the indigenous identity will be stripped away so that these projects can be successful. It will take a long time for substantial change to take place. In order to make sure their activities are culturally safe and meaningfully involved with the indigenous communities, Attapadi must implement mechanisms and processes within its various departments. Having a governance mechanism that integrates the traditional systems of indigenous communities requires the implementation of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) (PESA) Act, 1996.

The issue of reclaiming alienated property is more political than legal. The challenge in Kerala demands that all political parties step up to the plate and find a solution grounded in social justice. Establishing more committees will only lead to more legal quagmires and longer resolution times for indigenous claimants. It will not be possible to improve infant mortality rates in Attapadi by setting up hospitals, posting more doctors, or growing millet unless a fundamental shift is made.

edited and published by nikita sharma